...He stayed

The whole time he was at the Bodies till

They moved him. (Philip Larkin, ‘Mr Bleaney’)

Lodger. It sounds a sad thing. Still, whenever talk turns to houses and someone happens to ask if I own, it seems best to own up. I am a lodger. Not a tenant or lease-holder or anything else, but a lodger, renting a room with no contract in someone else’s house. It’s a peaceful, affordable room at the top of a handsome house, with a garden in summer and cats all year round. I’m treated very kindly and I do call this home, but after perks and excuses it is lodging all the same. Meanwhile friends, in their wisdom, are depositing and mortgaging and getting floors done.

Of course, I’ve no more right to carp about property than I have to property itself. Home-owning is a complex and uncomfortable aspiration, one which strains the frayed ligature between what I want and what’s expected of me. Particulars, surveyors, gazumping and deeds are things that happened to my parents and, like cufflinks and car-keys, always seemed part of the regalia of growing up. And this means that now that I am 30, I am a lodger with small anxieties about property – and whether adult life will ever coincide with what it looked like from childhood. And so what?

One way to look at these anxieties is to muffle their psychological noise. For might they be not merely fixtures in the head of a lodger, but also somehow characterise the cultural disquiet this marginal figure cannot help but embody? The literary historian Sharon Marcus points out that as early as the 1840s – as the Victorian domestic ideal firmed up in the wake of a widespread separation between home and the work-place, and its attendant boom in speculative house-building – lodgers took on an unsavoury, even menacing aspect. In part, this was because the shabby, urban lodging-house, which blurred people and spaces and who-did-what-where, provided a seemingly anti-domestic model of dwelling against which the middle-class household could be evaluated. But it was also because a version of the lodger might encroach on the life of that household itself. The term, after all, encompasses all manner of solitaries of both sexes – from the destitute to the dandy.

For no sooner did the ideal take hold of home as an individuated space, demarcated by four walls and with a discrete entrance from the street, than the fudging began. Home-owners, tenants, and even sub-letters strove to uphold what that space ought to house, and sustain the imagined connection between property and propriety: the hierarchy of types of occupancy seemed to advertise the impermanence of many domestic situations, while meagre opportunities for freehold led the nation, wrote Ruskin, to ‘look upon our houses as mere temporary lodgings’. The privacy of home sometimes needed to be subsidised to prevent its economic subsidence, and one solution was to bring in lodgers or paying guests. The price of private life could also be its tarnishing.

People take lodgers for reasons other than purely economic – for company or from kindness, or because they have space – and recent politicking about spare bedrooms suggests that attitudes towards property are themselves in transition. But so far as *his* historical status is connected to the cost of domestic ideals, the lodger has inevitably been represented as a dislodger, undermining the stability of what rent ought to fortify. The word and its cognates are fidgety and disruptive: a lodger might just as well be the person housing as housed, since the verb transitively allows someone to lodge somebody, but intransitively forces someone to lodge somewhere. It’s as if the word knows it describes something that makes dwelling vulnerable – as the compromises made by temporary residents seem to transfer to their hosts.

Put another way, while a lodger’s routine may be subject to any number of rules and restrictions, allowing a stranger to share home and its facilities is liable to limit one’s own privacy and domestic behaviour. After all, strictures also determine the habits of those who enforce them – like the gaoler in clinking duet with his prisoners’ timetable – as well as exaggerating the visibility of those things they can never fully control, such as bodily functions with their smells and accidents.

I am often asked whether my mealtimes are fixed, if I have to keep hours, and even, once or twice, how I stomach the celibacy (in some people’s minds, the idea of lodging conjures a version of bachelordom or spinsterhood that is decades too late). This type of dwelling implies a circumscribed domesticity, in my case happily based on lenient and unspoken courtesies, but in other situations no doubt set down and policed. For Gordon Comstock, the dingy lodger hero of George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), the foremost infringements are brewing and screwing: ‘This tea-making was the major household offence, next to bringing a woman in’. (The lodger’s nocturnal misdemeanours have their own brassy genealogy: ‘Roger the Lodger’, an old music-hall turn, descends from Nicholas, Chaucer’s priapic lodger-clerk in The Miller's Tale).

Orwell’s novel is very good on how sharing space with strangers inverts how we live: the hallways and landings of Mrs Wisbeach’s lodging-house are not places to pause but to hurry through; the noises off, heard through doors or thin walls, are not comfortingly familiar but remorselessly alien; mealtimes fail to bring reprieve. Other grubby novels of the period, chief among them Patrick Hamilton’s, are equally wise to how the noises, smells and sights that a house usually keeps hidden become public – that is, shared but never communal – in the presence of lodgers, in an amplification of the embarrassments of home.

Slaves of Solitude (1946), for instance, unravels in the Rosamund Tea Rooms, a generic boarding-house outside London where inhabitants take rooms to see out the war; they cannot help but live in earshot of other people’s petty indiscretions and, as it eventually turns out, the real noise of life. It is impossible for Miss Roach, Hamilton’s protagonist, to scuttle past fellow boarders’ ordeals:

She climbed the stairs, and the groaning met her as she rose. ‘Oh!… Oh!… Oh!…’

Mr Thwaites’ door was closed, and she listened outside.

‘Oh!… Oh!… Oh!…’ she heard, and, beneath this noise, the sound of two strange men talking in quiet and level tones. Only doctors, and frightened doctors at that, would be talking in just that quiet and level way.

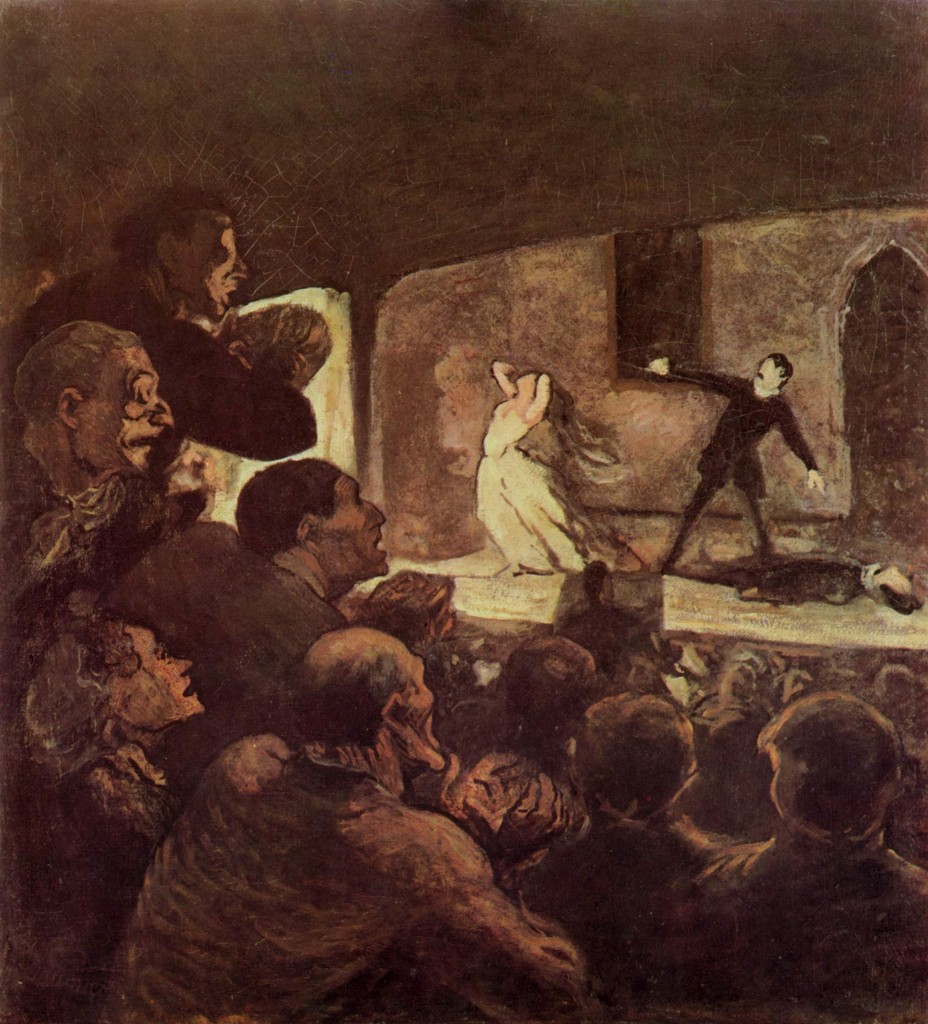

In other contexts, ‘Oh!… Oh!… Oh!…’ might titillate or kindle comic misunderstandings. Indeed, elsewhere the spilt sounds of lodging do provide grounds for mystery or comedy. In The Ladykillers (1955), the crooks take for granted the meddlesome credulity of the little old landlady; knowing she’ll swoon at his door, ‘Professor’ Marcus, her lodger, sticks a minuet on the gramophone, while his bogus string quintet plan and bungle a heist. Or take Hitchcock’s title, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), in which the sound made by a lodger – the sound made by ‘lodger’ – acoustically breeds the nebulous city he stalks through. (The film, like so many of the best silent movies, truly enjoys the noise it can’t make; there is a memorable shot of a ceiling that dissolves to glass to render the sound of the furtive lodger as he paces overhead).

To urban writers, in particular, fixated so often on achieving rooms of their own, the figure of the lodger clearly resonates with professional anxieties about the durability of writing and the shortfalls of the spaces in which it takes place. Lodging is a reminder not only of the transience of what is supposed to endure, but also that what is temporary can inadvertently become permanent – as lodgers become lodged, like pieces of shrapnel.

‘He stayed / The whole time he was at the Bodies till / They moved him’: I used to read Larkin’s lines as a euphemistic description of Mr Bleaney’s death, as if he had been carted from his rented box-room in a box still more compact. But looking again, he might just as well have been assigned to shift-work elsewhere, so that what I took for an ending was just transition elsewhere. ‘Sometimes I feel I’ve got to move on, so I pack a bag’, sings David Bowie in ‘Move On’, the third track on Lodger (1979). The album’s gatefold sleeve shows him splayed on the ground, with his broken-nose bandaged – a repeat jumper from a rented window. You never know with the lodger, quite where he is going.