In his À la recherche du temps perdu Marcel Proust writes of memories unfurling and unfolding like Japanese paper flowers suspended in water – from small seedlike bundles into fragile and exquisite miniature villages. Try as he might to control and artificially instigate the flow of reverie and trance into which he is so often plunged – whether from the confines of his cork-lined room or while he retraces his steps in the twilight hours – he finds that he must wait for the past to descend upon him.

Perhaps the most famous episode in the book is his encounter with a small cake, a madeleine, which brings back a world about which he had largely forgotten. For the great master of remembrance, the world is pregnant with such sensory triggers – madeleines – keys to unlocking forgotten doors which lead to vast networks of significance, cascading layers and delicate schematics of voice, tone, shade and place, that we had forgotten were contained within us, and which we may feel are in danger of dissolving into dust at a touch.

Recent experimental research on memory seems to at least partially confirm aspects of this Proustian picture. It suggests that the act of remembering is like taking something out of a jar, reconstructing it, and placing it back. Like a drawing that has been endlessly retraced, or a whisper that has been endlessly repeated, the image may gradually diverge from the original. The more we remember something, the more it takes on a character that the original experience may not necessarily have had. The greatest potential for revelatory reminiscences – madeleine moments – lies with those memories which have been least touched, least coloured by their position within the ever evolving edifices that we are.

This goes against long held conceptions of memory as a fixed impression of events which can be recovered through probing and interrogation – from Plato’s view that through a dialectical process of anamnesis, recollection, we can recall the eternal truths that our souls were acquainted with before we were born, to the psychoanalyst’s view that through a discursive process of personal archaeology we can peel back the layers to uncover the truth of the past. We constantly rewrite ourselves and remould our past. Those neglected extremities which are strangely fresh and less familiar to us are either re-illuminated, and hence redrafted, or otherwise remain shrouded in obscurity. After successive redrafting one might reasonably expect harmony and resonance to win out over accuracy. Meaningful shapes come into relief out of the raw blocks of sense, becoming more familiar with every recollection. These shapes are shoehorned into recognisable motifs and recurring patterns, which characterise not only the near and distant past, but also our immediate experience, as it settles into our malleable mental wax.

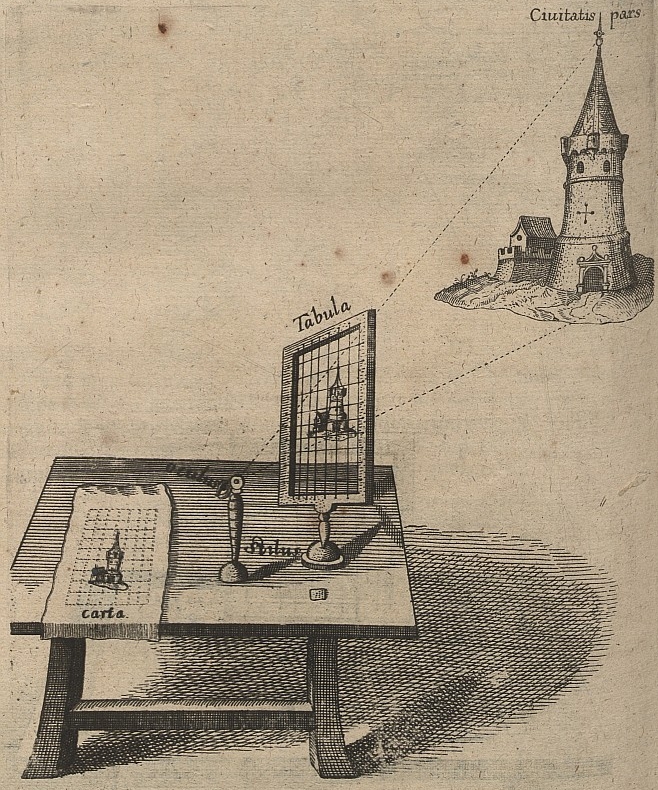

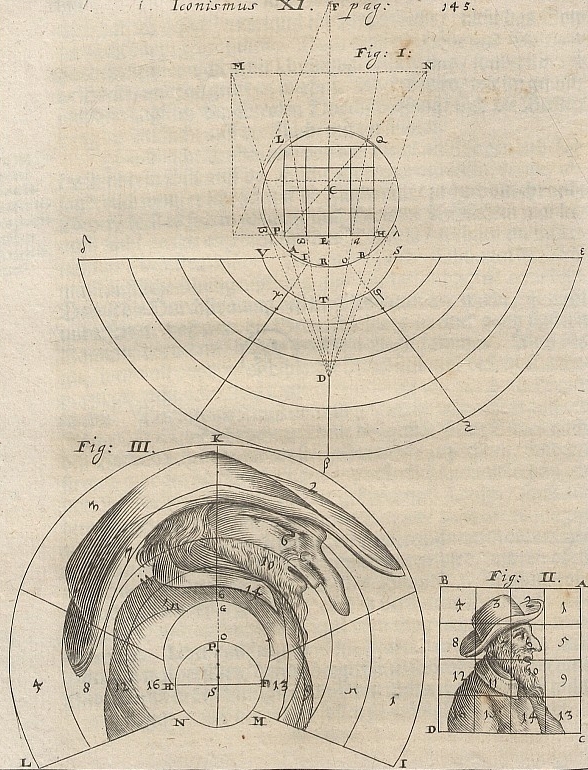

This process of fixing and reforming, reworking and remoulding is a fundamental part of what it is to be human. First and foremost, we formulate and negotiate versions of occurrences in language, which furnishes us with our universe of meanings, an immense constellation of semantic planets, small centres of gravity around which sense and memory can cluster. For millennia we have translated, transformed, and transfigured our individual and shared memories into conversation, ink, paper, singing, music, painting, performance: ornate figures, steps, the vibration of vocal chords, string, reeds, pipes, brass, patterns of colour depicting scenes with increasing accuracy and resemblance, aided by mirrors and secret techniques.

*

Technologies that capture and reproduce light and sound have dramatically enlarged the possibilities for articulating and retelling what happens to us, such that we have been able to sing with moving images and paint with sound. By moving from a state of speculative investigation and serendipitous discovery to highly organised reconnaissance raids on creation’s secrets, our vocabulary for representing things has expanded at an astonishing rate. We are creating an increasingly rich electronic echo of our experience and of the world around us – harvesting light, sound, movement, signal, speech and touch, transmitted and synchronised using invisible waves and configurations of light and magnetism. While we still think of memories being captured, stored and replayed in the form of physical objects – paintings, books, wax discs, tape cartridges, compact discs, hard drives, and electronic devices – we are moving towards a world in which our memories will surround us, whether through new display technologies, retinal projection or direct neural interfaces.

One wonders how an all-encompassing electronic echo might affect the way we create and relate to our memories. What are the implications of having a comprehensive record of all we experience? What if we could be confronted with an all-singing, all-dancing sensory reproduction of those precious, Proustian madeleine moments? What if the complete annals of the recent past, previously consigned to the book of nature or the mind of God, were thrown open to us? Would our experience of recollection be augmented by access to all of this detail – or would it destroy our ability to form memories, like a sculptor who is unable to let marble fall from the block?

Will direct and continuous access to the stuff of memory give us privileged insights into the nature and shape of our lives as a whole? Will it help to lift us up above the corridors of time, to reflect upon our whims, habits, decisions, or to give us insight into the texture of our existence? We hear that those on the brink of death see their whole lives flash before them in an instant, often accompanied by a feeling of ecstatic revelation. Jorge Luis Borges writes of the realisation that the paths that one has taken in life trace the contours of one’s face. In a Borgesian moment, W.G. Sebald recounts a dream in which he realises that the maze in which he has been wandering represents a cross-section of his brain. In these moments of revelation we are raised up above the accumulated sprawl of sense, the tangled morass of crossing paths, and we witness shape and meaning in the whole that it was not previously possible to perceive. In the fifteenth century, painters used a technique known as anamorphosis to create paintings which apparently depicted strange chaotic scenes or monstrous landscapes, but which, viewed from a specific spot, revealed saints, sacred visions or secrets. Being able to witness our whole lives spread out before us could well be an experience akin to that of seeing the earth from space for the first time: an unexpected, awe-inspiring apparition that, at least temporarily, transfigures our time spent in the thick of things.

Perhaps we might imagine that being given access to an archive of our every moment might help to give us a perspective on our life that usually evades us in our imperfect, partial, and ad hoc acts of sense-making and reflection that we engage in every day. While our mind and sensory apparatus grasp things and concepts which are forged from the heat of a colossal subterranean current of innumerable instances– from our earliest experiences of a given object or idea, to our most recent acquaintances with it – what would it be like to be confronted with every case at any moment? While we may have more or less insistent hints and insinuations of past experiences in our daily lives, what would it be like to be able to see every apple that we have ever seen, to witness every shade of blue, to access every interaction with a given person, to see the context of our hearing, reading or speaking any given word, to call to mind every time that we have stood at a certain spot, eaten a certain combination of foods, listened to a certain song, tilted our head at a certain angle, breathed in a precise volume of air, witnessed a certain hue combined with a certain humidity?

How might we utilise such a rich record of the past? We usually ignore, discard or overlook the shadow of transactional detritus that accumulates around us as we move through our lives. Might our electronic echo mimic the functioning of our memory and strategies we presently employ to keep what we need and value close, and to consign what we do not need to distant perimeters? One can imagine algorithms to assist us with emphasising and de-emphasising aspects of our echo. Perhaps our technologies to artificially augment recollection will imitate the natural functioning of our memory in the same way our floating and flying machines imitate insects and birds. Perhaps our electronic echo will recreate not only the stuff of memory, but also the ways in which we filter, select and posit patterns, the inscrutable manner in which certain memories present themselves to us. Or perhaps we might conceive of radical new ways to explore, organise and analyse our memories – synthesising disparate aspects of our experience or sorting the past by some arbitrary attribute: to see an alphabetical list of every word that we have spoken, to see every ellipse or rectangle of given dimensions that we have seen, to feel every motion within a given range of velocities, to witness every episode with certain light conditions accompanied by a given temperature, to see every mass or structure that has risen before us at a certain angle, with a certain shape. In addition to new kinds of forensic autobiography one can imagine the emergence of new cultural forms: elaborate synesthetic symphonies, immersive sensory collages, concatenated litanies of time.

*

While we will no doubt continue to contrive ever more cunning machines to capture and reproduce our experience of the world, ultimately we must all confront the finitude of our situation, which is the end of all remembering. While we may be able to leave behind us an archive of all that we have seen, heard and felt, the significance of these things is difficult for others to comprehend without our being present to confer meaning on them. When we attempt to communicate to others the significance of things that happen to us we either assume a background of shared experience, or – through conversations or cultural artefacts, paintings or Proustian narratives – we must attempt to reconstruct a picture of our past which highlights why something holds meaning for us in the way that it does. While the tree makes fruit and the bee makes honey, we humans manufacture and traffic in meaning, and the sensory stuff out of which this is created is like dust or pollen. Artefacts that we leave – whether paintings or photographs, recordings or receipts – gain significance insofar as they relate to the narratives or sensibilities of other people, as agents of meaning. Without us there to frame, contextualise, curate or explain it, our electronic estate, the raw register of our experience, would appear as a colourful vapour encircling a black hole. It is strange to contemplate that while people of the past have left us ruins and fragments, one day we will leave incomprehensibly vast electronic corpora, like complexes of buildings and spaces, staircases and corridors, exhibition rooms and waiting rooms, lobbies and altars, gardens and libraries – with tables laid, fires lit, and objects arranged in anticipation of we know not what, without a person in sight to explain what any of it means.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.