The iron railing is one of the most pervasive yet rarely remarked features of the London cityscape. A form of street furniture that proliferated in the industrial revolution, London’s railings mark the loss of an urban commons, a loss that accompanied the privatisation of the countryside that successive ‘Enclosure Acts’ enabled. Dividing space into public and private, railings exert power within the streets and squares of the city to enforce geographical restrictions of people and behaviour. Most of the time, however, they are barely noticed at all.

In an article titled ‘Art in the Streets’, which appeared in the journal Magazine of Art in 1880, the critic Percy Fitzgerald suggested this was precisely the point. Railings, he argued, fused two functions, one aesthetic and the other social. Criticising the overly elaborate design principles of manufacturers from the period for failing to maintain a balance between these purposes, he says the ‘failure arises from misapprehending the…object of a railing’, which is ‘to allow as perfect a view of the enclosed space as is consistent with exclusion’. ‘There is’, Fitzgerald continues, ‘to be as much enjoyment for the eye as though the railing were away, yet the barrier must be as effective as though it were a wall.’ On the one hand, Fitzgerald points out something quite obvious: that the bars in railings need to be spaced with due attention to the demands at once of security and openness. But he also highlights something rather interestingly unstable about the essence of this everyday thing. The two functions of railings might, after all, pull in opposite directions. Can the bars of railings, however thin, really allow ‘perfect’ vision, whilst also maintaining absolute security? As Thomas Pennant remarked in his early tourist guide to the fast changing capital, Of London (1790), the railings in London are ‘benevolent’, granting the excluded a kind of license to see what they are barred from enjoying physically. Railings are more inviting, more generous than walls.

Heralding both visual freedom and physical limitation, then, railings are fascinatingly double. Giving and withholding in different ways, they manifest themselves most ideally when they are not themselves paid attention; intervening in the spatial ambitions of the people who look on and through them without interrupting their aesthetic contemplation. It is this complex quality of railings that Manet knew, made use of and subverted in Le Chemin de Fer (1872), which steadies the little hand of the girl with her back to us clutching at the bar as she looks through into the steamy, smoky railway station. Modernistically cutting out and blowing up what would in traditional composition be a fragment, the railings, which should conventionally barely register in the background, are in this painting made strikingly present to the eye.

Manet may have been drawn to the very predictable banality of the railings in Parisian streets, but others have discovered in their ‘personality’ something more attention-seeking. While the severe cropping in Le Chemin de Fer leaves much to the viewer’s imagination, some representations pay homage to the highly decorated summits the iron bars often sport, revelling in the ornamentation of which Fitzgerald disapproved. The mechanically repeated bars of railings may be as blank and unreadable as the gaze of the facing figure in Manet’s painting – inviting the passer-by to look through but not pass through them – but the florid and bellicose ‘finials’ crowning these bars announce a contradictory imperative. G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904) finds in the design of these ornaments not reticent efficiency but an extravagant and spectacular atavism. When the emperor of the book’s title, Adam Wayne, exclaims how railings ‘stir one’s blood’, the narrator derives his enthusiasm back to the war-flavoured dreams of his infancy:

As a child, Wayne had half unconsciously compared [the railings] with the spears in pictures of Lancelot and St. George, and had grown up under the shadow of the graphic association. Now, whenever he looked at them, they were simply the serried weapons that made a hedge of steel round the sacred homes of Notting Hill. He could not have cleansed his mind of that meaning even if he tried. It was not a fanciful comparison, or anything like it. It would not have been true to say that the familiar railings reminded him of spears; it would have been far truer to say that the familiar spears occasionally reminded him of railings.

Wayne intuits that in the spear-like tops of railings we witness the Londoner’s house truly as his castle. In the context of a novel that goes on to explore how aggressive imperialism might be not only countered but also secretly fostered by a defensive sense of local patriotism, the ‘serried weapons’ of Wayne’s ‘graphic association’ cast long shadows indeed. Wayne has not attempted to ‘cleanse’ the association from his mind, but as the narrator suggests, this proleptic stain of imperial blood-thirstiness appears to be, like those on Lady Macbeth’s hands, ineradicable.

While Chesterton explores the way the railings around the domestic sites of an imperial metropolis bear symbolic resonances of wars fought elsewhere, or wars yet to be fought here, in Mrs Dalloway (1927) these weapons see action in a more material sense. In Woolf’s novel, cast iron is pressed into a kind of post-military service when its seemingly shell-shocked character Septimus Warren Smith throws himself out of his lodging house window to become ‘mangled’ upon Mrs Filmer’s area railings. Septimus’ suicide has itself become somewhat mangled in critical analysis. So implicated has the act become in our understanding of Woolf’s own fraught engagements with medicine, in the light of our retrospective knowledge of her own suicide, that the full distinctiveness of her fictional intervention in Mrs Dalloway has failed to be appreciated. To be fair, Woolf herself encouraged this mangling, by acknowledging in a letter an autobiographical source to the episode. Writing to Gwen Raverat on 1 May 1925, the novelist explains that the suicide of Septimus Warren Smith related to her own experiences:

What you say about Mrs Dalloway is exactly what I was after. I had a sort of terror that I had inflicted something on you, sending you that book at that moment. I will look at the scenes you mention [the madness and suicide of Septimus Warren Smith]. It was a subject that I have kept cooling in my mind until I felt I could touch it without bursting into flame all over. You can’t think what a raging furnace it is still to me – madness and doctors and being forced. But let’s change the subject.

Mrs Dalloway may well partly reprocess Woolf’s own experiences in Harley Street, but we need nonetheless to resist reducing it to a prefiguration of her final suicide by drowning. The method of Septimus’s suicide in impaling himself on Bloomsbury railings is highly specific and has particular cultural resonances. Given the substantial critical analysis devoted to the metropolitan geography of the novel, it is surprising, for instance, how little this suicide has been recognised as one of its most hyper-urban motifs: by its appropriation of the very street furniture it makes the city participate in Septimus’s death. If we accept Chesterton’s idea that the tops of London’s railings have something spear-like and therefore militaristic about them, moreover, it seems likely that we are being prodded to recognise a connection between the medieval weapons of war that anachronistically ornament our streets and the psychic disruptions that symptomise the conscripted total wars of early 20th-century modernity. To put it another way, the cast iron spear that puts an end to Septimus’s life might be understood as a traumatic after-spasm the First World War.

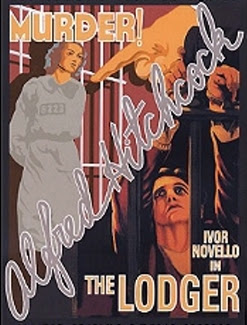

If Woolf’s novel borrows railings to underscore the medieval brutality of the Great War, a film from the same period casts its glance forwards to the development of a kind of vigilante populism that would soon be institutionally embodied in Nazi Germany. In The Lodger (1927), Alfred Hitchcock recruits railings for a scene that is potentially farcical but actually terrifying and pathetic: the handcuffed hero, played by Ivor Novello, becomes accidentally chained to an iron fence and thus is left dangling at the mercy of a mob that has misattributed Ripper-esque serial murders to him. Here the railings perform a function like that of their cousins, prison bars: they restrict the physical movements not partially but completely, making the ‘excluded’ not the subject of visual pleasure but the object of mass spectacle, immobilising him and handing him over to the vigilante violence of a crowd that has run mad. If Woolf’s railings had collaborated in the suicide of a man driven mad by modernity, Hitchcock’s seem to carry anxieties about authoritarian democracy overreaching itself; about fascism, indeed, as these railings appear to will on, enable and endorse the murderous rages of the misinformed masses.

Railings, then, can be flagrantly potent as well as reticently impassive, as the scenes of physical violence staged upon or around them that are imagined by early 20th-century figures such as Chesterton, Woolf and Hitchcock insist. But it is in their muted banality that railings most effectively perform the oppressive political agenda for which they are erected. The radical William Morris meets this apparent paradox head on and reveals the oppression that can be concealed by reticence in his utopian romance, News from Nowhere (1890). Here the railings have been tellingly removed from around Kensington Gardens and the British Museum to exemplify the post-revolutionary city’s transformed social space. The very absence of railings from the London scene denaturalises them for the reader, since they are an object that is usually barely noticed. Thus begins a chain of speculative thought about what kinds of violence, threatened and ideological as well as actual, might have been necessary to maintain their presence in the city for so long. Absent, the railings of Morris’s future may well be stained with the blood of martyrs: the workers who fought in the revolution that forms the book’s key back-story.

The sentiment Chesterton’s character expresses when he encounters these apparently boring everyday objects strikes us at first as unhinged. When we consider fully how railings operate within the social sphere, however, they might well ‘stir the blood’ more forcibly. Railings enforce social hierarchies and curb the public potential of the park and square, but they do so by being less noticeable than either the flagrant appropriations Woolf and Hitchcock inscribe or the absence Morris secures.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.