How can we comprehend a capital city? You might start with its own consecrated places: the palace, the parliament, the cathedral, the stock exchange. From the top deck of a tourist bus, the story that the city tells about its enduring pre-eminence can be read smoothly. Or you might, as learned psychogeographers do, drift away from the throngs to decipher, through happy accident, the palimpsest of buried or forgotten histories in more obscure locales.

Both these approaches leave out a great deal: the first is devoid of the turbulence of human life; the second, a little too satisfied with its esoteric knowledge. I don’t wish to sound bluffly anti-intellectual by invoking the man in the street, but cities, if they are made of any basic substance, are made of men – and women – in streets. Understanding the fluctuations of the present – how people flow through the city, how capital flows through them – is beyond the capabilities of the tour guide or even the shimmering consciousness of the deriviste, however alert he may be. To plot such a heat map is an arduous, perhaps impossible task. It proved so for Walter Benjamin, despite his Arcades Project – his incomplete compendium of clippings and observations on 19th-century Parisian life – having the clarifying perspective of a century-long hiatus.

Another, less well-known study of Paris gives a revelatory account of a city as a living organism, in all its morphogenic complexity. Between 1782 and 1788 Louis-Sébastien Mercier wrote 2,000 essays, collected under the title of Tableau de Paris, about life in the city. And it was the life he was interested in: ‘I am going to speak of Paris,’ he began his Preface, ‘not of its buildings, its churches, its monuments, its curiosities, etc., since enough has been written about them. I will describe public and private behaviour, dominant ideas and the public mood, and everything that has struck me in this odd assemblage of silly and sensible, but constantly changing, customs’. The evanescent aspects of urban living – those least likely to be recorded – interested him the most.

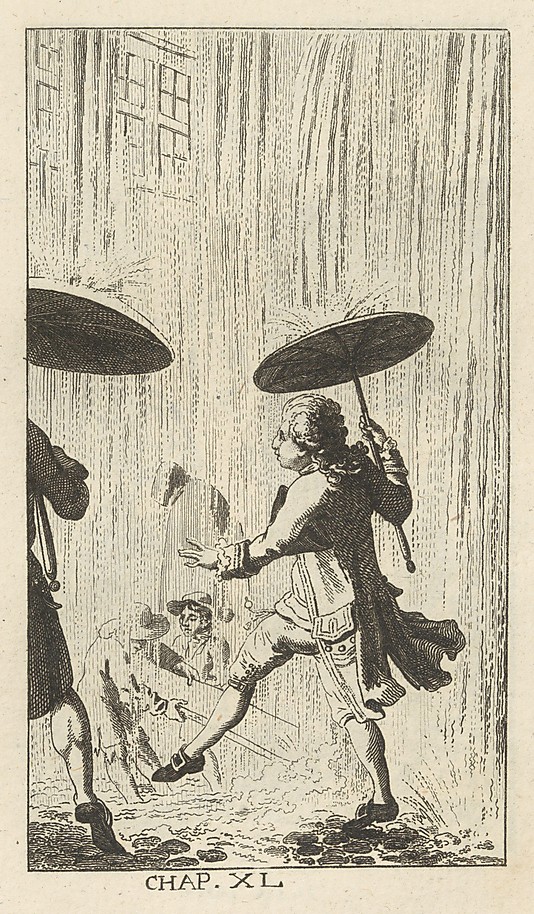

Balthasar Anton Dunker, Tableau de Paris, ou Explication de Differentes Figures, gravées a l’eau-forte, pour servir aux différentes Editions du Tableau de Paris… (1787)

He wrote of attics and chimneys and window boxes; of butchers and wig makers and salt carriers; of secretaries, clerks, booksellers and actors; of jewellery, hairstyles, hats, gardens and little dogs; of taxes, customs barriers, hospitals, prisons and academies. Melons get their own chapter, as do the bureau of childminders, pavements, crockery, tavern signs and lamp wicks. To his rampant curiosity, nothing is too insignificant or devoid of interest.

Essay by essay, Mercier assembled a masterpiece of observational journalism and a repository of urban lore. We learn, for example, that Monsieur Maille, purveyor of the mustard still sold under his name, keeps below the counter a ‘vinegar’, much in demand from brides-to-be who worried that their chastity might be questioned on their wedding night: its ‘effects restore confidence in her and inspire it in her husband’.

The Tableau de Paris is also a pioneering work of anthropology, a discipline then in its infancy. The French reading public had devoured the comte de Bougainville’s account of his expedition to Polynesia and his observations on Tahitian society; and there was an established tradition in French letters of ventriloquised foreigners delivering social critique, Montesquieu’s Persian Letters and Madame de Graffigny’s Letters of a Peruvian Woman being two well-known examples. Mercier stripped away their comic estrangement. He was a participant observer and, though he claimed to be dispassionate – ‘I have only wanted to depict, and not to judge’ – his impartiality often lapsed in saeva indignatio. His tone is that of a child pressing his nose up again the pane of the sweetshop window, yearning to be let in and resentful at being deprived. It’s there in his complaints of the fashionable women who turn their boxes at the theatre into boudoirs, ‘in which they recline with a spaniel or two, cushions, a footwarmer, and a small pet imbecile with a spyglass, who tells them who’s who in the audience, and the names of the actors’, while ‘outside, money in hand, disappointed playgoers are turned away from the ticket office; there is no room for them.’

And it is there when he triumphantly recounts the tale of a ‘poor but ingenious person’ who, able to afford only the single lace ruff, finagled his way into a grand hôtel by hiding his other hand beneath his coattails. ‘But in the abandon of conversation, forgetting prudence in gesticulation, he had the ill-luck to withdraw his obscene wrist from obscurity and flourish it before the scandalised eyes of the whole drawing-room.’ The inattentive porter received such a dressing down that, on the following evening, an officer who had lost an arm in battle struggled to gain entry. In such little victories did Mercier’s ressentiment find release.

Mercier had been born in 1740 into a petit bourgeois family. His father was an armourer who educated him to a sufficiently high standard that he aspired to become a man of letters – one of the Rousseau du ruisseau (‘Rousseaus of the gutter’), who scratched out a meagre existence with their pens. Mercier was immensely prolific, composing, besides the Tableau de Paris (and its sequel about the city after the Revolution, Le Nouveau Paris), a dictionary of neologisms and a science-fiction novel, The Year 2440, which imagined a remodelled Paris in which the Bastille had been pulled down and the clogged streets replaced by spacious boulevards. Despite being banned, it was one of the most successful books of the 18th-century and at least 25 editions were published before the Revolution. Mercier considered himself a playwright and he wrote more than 60 plays. But his involvement in a polemical dispute over the direction of French theatre – he advocated the bourgeois drames written by the likes of himself, Diderot and Beaumarchais over the classical tragedy of Racine and the comedy of Molière – saw him anathematised by the Comédie-Française. The Tableau de Paris offers glimpses of his dramatic talent in a number of dialogues, such as the bargaining between a woman wishing to mortgage her annual income and deliciously world-weary buyer of annuities (‘Yesterday, madame, I had the offer of buying up four thousand francs a year; but I didn’t accept. Why? Because I’d heard that the lady in question was forever going to balls. One night’s dancing may be deadly … You might break your neck going down the stairs…And then, what about revolutions?’).

Repeatedly in his essays, Mercier returns to the theatre. His gripes about his treatment as both a playwright and a theatregoer – at the overweening power of actors, at the cost, at the ‘grenadier [who] packs you together tight as onions on a string’ – arise, in part, from bitterness at his treatment. But his obsession with the theatre was intellectual as much as professional. Social performance was his subject matter. It was the city’s animating spirit – at the beating heart of things stood this temple of the Parisians’ religion, the one place members from all the strata of society came together, to see and be seen.

Mercier was an instinctive taxonomist and relished making subtle discriminations by profession and status. He is close in spirit to those Enlightenment classifiers, such as Linnaeus and the authors of the Encyclopédie. Mercier had an eye for what he calls ‘structure of disorder’. One chapter presents eight social classes: ‘princes and great lords (the least numerous), professionals, financiers, merchants or store-owners, artists, artisans, manual labourers, servants and the poor’. Each of these is subdivided further. Financiers can be ranked from ‘the head of the tax-farm to those who make personal loans for a week at a time’. And there are nuances that are lost on less perceptive Parisians: ‘Out of ignorance, the bourgeoisie confuses artists and men of letters; there is a great difference between them. The man of letters of is far more than an artist; if Corneille and Molière had had their arms cut off, they would still have been Corneille and Molière.’

Immigrants from the rest of France devote themselves to preordained professions. ‘The Savoyards brush mud off pedestrians, polish floors, and saw wood; almost all of the Auvergnats are water-carriers; the Limousins are masons; the Lyonnais are porters and sedan-chair carriers; the Normans, stone-cutters, pavers and peddlers, they repair broken china and sell rabbit-skins; Gascons are wigmakers and surgeons’ assistants; those from Lorraine are itinerant cobblers, known as carreleurs and recarreleurs.’ The list shows Mercier’s characteristic brilliance at bringing a class of people alive. What skills, we rack our brains, might wigmakers and surgeons’ assistants have in common? Can one make a living just by selling rabbit-skins or do you need to repair a bit of china on the side? Why are the Lyonnais so strong? And just what are the rest of Auvergnats doing? In a brief list, archetypes gain depth and body. His characters may be defined only by region or occupation, but they are never mere sociological ciphers. Would it make a difference if we knew the name of the beadle that ‘brings a little sugar and wine; and then that voice which launched its lightening down the nave, announcing judgement, anathema, eternal damnation, dwindles to drawing-room smoothness with its: “A macaroon, dear lady? Marzipan? Pray accept a biscuit’”. Few other writers can inject life into the stereotypical so magically.

Balthasar Anton Dunker, Tableau de Paris, ou Explication de Differentes Figures, gravées a l’eau-forte, pour servir aux différentes Editions du Tableau de Paris… (1787)

Diatribe is Mercier’s chosen mode though he is not – or not just – a nostalgic curmudgeon. One chapter is entitled ‘Silly Customs done away with’. His concerns about consumerism (‘Tranquillity is lost; desires become more intense; luxuries become necessities; and the needs that nature gives us are far less tyrannical than those that social pressure inspires’) and pollution (‘So much smoke! So many flames! What an inundation of vapours and fumes! The soil must be saturated with all the chemicals that nature has distributed in the four parts of the world’) resonate today. But so much is viewed with a jaundiced eye: the police (‘wholly corrupt’), people who don’t light street lights when there is a full moon, people who hang street lights on arms extended over the street rather than brackets against the wall, markets (‘the fish stalls are unspeakable’), bureaucracy (he coined the word – pejoratively), Carthusian monks, bankers (no change there), doctors (‘the science of medicine is to-day nothing more than a brazen and accredited charlatanism’), street performers, people who stand around gawping at street performers, the height at which theatre posters are posted (‘too high’) and gutters, to mention only a few.

But above all else, Mercier despised carriages. He was a lover of walking. ‘I have been about so much while drawing my Tableau de Paris that I may be said to have drawn it with my legs,’ he wrote. Yet researching his book meant placing himself in mortal danger from folk in cabriolets. Pedestrians flee ‘like game … before the menace of the gun’, he writes. ‘Paris is dishonoured by this criminal indifference to the lives of her citizens’.

Beneath the worry over physical safety, there is an antipathy to all that carriages represent. ‘A carriage is the goal of every man that set out upon the unclean road to riches … Nowadays the young man of fashion, instead of investing his capital in a country cottage, or a library, or a mistress, sinks it in a carriage’ – all because ladies of fashion ‘have refused to receive or consider any young man suspect of going on foot’. Rent and subsistence are sacrificed to maintain appearances. Carriages were the most potent symbol of Parisians’ insane appetite for luxury and potential bankruptcy was the necessary wager for social advancement.

Mercier was also worried that those on wheels annexed public space for private interests. The characters about whom he writes most fondly are all denizens of the street: the décrotteurs, who brush your clothes and polish your shoes (‘There are no jealousies among them … The strong and the weak take their turn; the clever fellow never makes mock of his clumsier colleague’); and the ‘ballad-singer with his ‘jolly and peaceable red face’. It is this good-humoured, honest, sociable way of life that is dispersed by careering vehicles. Mercier takes great pleasure in a chapter entitled ‘Balcony’ of describing the city when gridlocked: ‘In a gilded chariot, velvet-lined, with glass windows and a pair of horses exquisitely bred and matched, a duchess in all her regalia reclines; and there she remains, unable to get forward or back by reason of an old filthy cab, with boards on straps instead of glass, which is blocking the way.’ The carriage, a marker of social distinction, is crammed cheek by jowl against the lowlifes it is supposed to insulate its occupant from. The same forces that pump people about the city lard up its arteries. Paris was on the verge of a heart attack.

Why then, given his contempt for the ‘monstrous wealth, [the] scandalous luxury’, did Mercier remain? For one thing, he thought that provincials were gullible, lazy and hopeless at putting on nativity plays. And the energy in the city, misdirected though it may have been, invigorated him. As Mickey Sabbath, drawing back from suicide, put it at the end of Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theatre: ‘How could he leave? How could he go? Everything he hated was here.’

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.