I am in Brussels, numbering the Bruegels.

It is a project. I have drawn up a spreadsheet of all 42 painted Bruegel panels, and a further 10 penumbral Bruegel works – possible misattributions, copies of lost originals – which together constitute what I have come to think of as the Bruegel Object. I plan to see them – it – all.

So I am in Brussels where, according to my spreadsheet, 15.874% of the Bruegel Object is located.

I enter the corner room of the Musée des Beaux Arts where they put their Bruegels, and make a rapid audit. The right side of the room, more or less, is Pieter Bruegel the Elder; the left side is Pieter Brueghel the Younger, or others. I am here for the Elder Bruegel. Elder Bruegel is the great Bruegel. I ignore everything else, and settle to the business of scrutinising Bruegel.

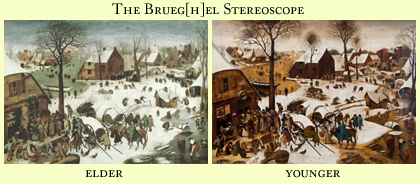

However, there is a distracting oddity. On the west wall of the room hangs the Elder’s Census at Bethlehem, a large panel painted in 1566. But on the south wall, roughly 8.5 metres away and hanging at an angle of 90 degrees to it, is another, near-identical Census at Bethlehem, painted by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger in about 1610. It is one of at least 13 copies the Younger made of the original, all of them faithful and well executed, but this the best among them.

I start by trying to ignore it: it is good, but it is hack work, a cynical workshop production, a pointless replica. I am here to focus. But it happens that there is a spot, situated at the apex of a triangle, the base of which is formed by the two paintings (considered as points, not as planes), where you can take them both in; if you had bovine eyes the whole corner would become a giant and blurry and (to your cow mind) bewildering stereoscope.

I do not have bovine eyes or a cow mind. If I want to play spot the difference – I do want to play spot the difference, in spite of myself – I have to swivel my head. And in reality, there is not one triangle at the apex of which you stand; rather, you stand in front of the Elder and glance at the Younger, far away; or you stand in front of the Younger, and look over your shoulder obliquely at the Elder. There are two triangles (at least); you move in a zone between their vertices.

And in this god-like, cow-like zone, what do you see?

In both cases, a snow-bound village scene dominated by children playing and scuffling in the snow, and their elders scratching out a living with their fardels and pigsblood and snowed-under carts, their various small and wintry concerns. Around the inn in the left foreground a small crowd gathers, submitting their names to the census; others trail in across the frozen river, and across the frozen pond. Mary and Joseph are unobtrusively there, Mary, riding on an ass, nine-tenths concealed in her blue robe, Joseph likewise hidden behind a large hat, but waggling a two-handed saw over his shoulder.

They are both as yet unnumbered.

*

For Pieter Bruegel the Elder, there was only ever one Census. It was a singular object. Unlike his son, he did not run an extensive workshop, did not bang out copies. He made few paintings, each one for the most part autograph.

When he died in 1569 at the age of about 44, his eldest son was five years old. In terms of art history, there is no genealogical connection between the two, merely a tectonic overlap. Pieter the Younger inherited a series of world-famous images (if by world you understand Northern and Hapsburg Europe), probably in sketch and cartoon form. His entire career down to his death in 1636 was grounded on these images, whether he was making direct copies or spinning genre pieces from them.

He most likely saw little of his father’s original work, much of it already carted away to the great imperial collections – hence no doubt the small differences which creep in, the errors in replication, the drift.

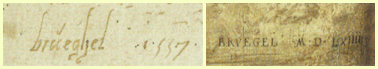

As with his name. Pieter the Elder had started out plain Pieter Brueghel of Breda, signing his name with a calligraphic flourish on the drawings he did as a young man. When he started painting in oils towards the end of the 1550s, he dropped the H and began signing his name Bruegel in chiselled capitals, usually with the date. Brueghel was a bit burgher, perhaps, a bit stomping peasant; Bruegel is cleaner, more Roman, befitting a Stoic observer of stomping peasants.

His son for some reason restored the H to his name. Father and son taken together make a blurry Brueg[h]el object.

*

So I stand at the invisible apex of my triangles, ticking off Brueg[h]els and playing spot the difference. It is a midweek morning in early January, raining outside the museum and largely empty inside. This is where my project has brought me, dead-reckoning in a room of old paintings.

I am 42. Not far off the age now at which the Elder died. Forty-two is the number of Bruegels on the spreadsheet. My own father as it happens died a year or two ago, aged 84. When I was born he was 44. I was the second son. There are two years between my brother and me. I have recently become a father myself, to two sons, between whom there are two years. Pieter Bruegel had two sons, the Younger, and Jan the Elder, between whom there was a fraction more than two years (the fraction in question admittedly being a half, so three years in fact).

And so on. You do not really explain an intersection by following up or down any of its convergent (or for that matter divergent) paths. It is sufficient that the mild panic of my mid-life is characterised by multiple convergent (divergent?) vectors: my dead father, my brother, my small sons, myself, and the Brueg[h]els. Many similar triangles.

*

The census is an unusual subject. Bruegel has painted one of the culminating moments of bureaucratic life. Bureaucracy is the science of docketing the routine comings and goings of existence – births and deaths, taxes paid and taxes owing; it is a rolling programme of work, one without end.

A census, however, is a one-off. It is a flourish of the bureaucrat’s art. You do not merely keep the ball of a census rolling: it wants planning and execution. It is, properly speaking, a project, a projection of bureaucracy. And it has an end: a Domesday book of taxable, pressable souls.

From a distance – to the administrator or historian – a census is an exercise in control and power, not always pleasant, but always impressive in its way, like a datastream ziggurat or Hoover Dam. Seen close to, however, it pixelates into a sequence of inexact iterations. The bureaucratic ground troops do not mechanically fill in blanks; they have to keep a weather eye cocked on the confusion of crowds; they have to sort quickly, roughly (there are only so many categories) but accurately. They have to fix a point in time where there are no points in time.

So Bruegel’s Census at Bethlehem is a world in transformation. The census is drawn through the village, through that mess of humanity at the inn-door, like the carding of wool – the stream of individuals passes back and forth over the frozen river, coming in nebulous and free to have their names written down in a book, their existence validated in ink; going out docketed and numbered, but also informed, no longer unlicked stray lumps of humanity but named individuals with a location and an occupation and a marital status, enjoying a spark of existence beyond their own clay.

*

When my father was dying in hospital, my brother was searching the census records of our paternal family.

My father was on the whole reticent with history. He had been born in 1925 in Camden, had grown up there and on Portpool Lane off Gray’s Inn Road, and in Lee Green. There were some disconnected anecdotes – a story about a broken radio, about a Jewish funeral, about an aunt who sprinkled sugar on his buttered bread – but not much else.

My brother uncovered various details and relayed them to my father in hospital: details of addresses (around Long Acre, Seven Dials) occupations (toffee maker, motor mechanic, seamstress), dates of births and deaths.

In truth all this was probably less use to him than the anecdotes, and in any case it was difficult to gauge his response – he was a polite man, but his circuit of interest seemed to have contracted to the point where all that concerned him were the minutiae of the routines that were eking out his life.

But for my brother and I, it assuaged the sense that here was a disconnected dot, about whom we knew not very much, going into the darkness. He was linked. So were we. There was a chain. It was written in the census.

*

People may be numberless, but the numbers have a shape and you can be located within them by a measurement of variance and discrepancy. So, spot the difference.

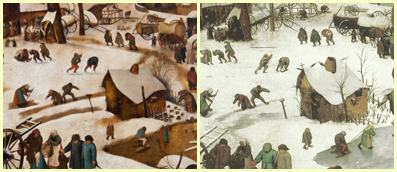

The Younger’s panel is fractionally larger (123 x 168.5 cm against 115.3 x 164.5 cm).

No two figures are dressed alike, fabrics change colour, there are odd reversals.

There are microscopic differences between faces, individual postures.

The Younger had his own way with trees, bushy rather than twiggy.

And then, more slowly, it dawns on me that the Younger favours tracks. From the bottom right, where Mary has entered on her donkey or ass, to the top left across the frozen river; and again, from the wheels of the foreground’s frozen carts, there are criss-cross tracks, paths, desire lines, animating the space. This is a frozen world, but there is evidence of networks, organised around an axis.

The Elder’s foreground carts, by contrast, are going nowhere. There are no paths, just yellowish ice wallows. He has painted a village of spindly cartwheels, a spindly ladder against a spindly barn, spindly trees; and he has painted a world of endlessly repeated circles – the wreath, the barrels, and especially the cartwheels, 33 of them, including one a fraction below dead centre, ghostly and snow-covered, hitched to no wagon and orthogonal to the viewer, as though it were a circuit diagram of village life, or a generative code for the cyclical passion of Christ.

And then finally I see it – so obtuse of me – what sets the two paintings apart: the Younger has raised the branches of the largest foreground tree a fraction of an inch to reveal what in the Elder there is none of – a vanishing point, or what the Italians call a punto di fuga, a fugitive point, a point of escape. The Younger’s brown frozen river winds out of the canvas, we can follow it through the canvas and away. By contrast, his father’s is entangled in the branches, perhaps coiling around the back of the village, a labyrinthine waterway.

The only thing vanishing is that peculiar sun. Or is it rising? It hardly matters. The world is ebbing to its conclusion.

The Younger – wittingly? unwittingly? – has made this dead cosmic circuitry bearable, transient; along those paths and on that frozen river our eye is made to criss-cross, not circle, and finally escape the painting. And he has done all this in direct contravention of the central thought process of the original – that these circles go nowhere for a reason. They mean something.

*

Pieter Bruegel the Younger may not have been a painter at all. He was unarguably an eminent man in the Antwerp art world – there is a portrait etching of him by Anthony van Dyck, in which, as it happens, he projects the sort of patient melancholy common to men with drooping noses and straggling moustaches. But he may only have been the inheritor of the cartoons, and the general manager of a workshop that employed anonymous hands to complete the copies. It is possible that he had no artistic personality at all, nothing but a signature and a locked chest of cartoons, which he carefully opened and closed as required, a bureaucrat among artists, ghosting through the system, the painted artefacts. The notion that somewhere in that swirl of hands and methods and corporate production was the memory of a five-year-old boy transfixed by the death of his father is nothing more than an absurd projection of my own.

But that, to repeat, is why I am here. I did not travel to Brussels to discover a truth, but somehow to impose one of my own. To make something of all this. This is one way in which we react to the accumulation of life. We make spreadsheets, trace genealogies, embark on projects, write essays. We pore over the data in search of patterns. All this must and will be made to mean something.

*

So I stand in the corner room of the Musée des Beaux Arts, deriving my geometry from the observation of small differences. Discriminating.

And there is in fact one final difference – a figure, present in the Elder’s panel but absent in all of the Younger’s copies, suggesting a late emendation on the father’s part, a final gratuitous flourish of his art: it is the youth pulling on his skates, below the tiny child who cannot yet summon the courage to go out on the ice.

Life is treacherous, says the figure, but we have resources. We have skates. We can make of this treacherous ice our element. Sooner or later, we all pull on our skates and go out on the ice – as the father might have remarked to the son, had he had time.

This whole village, in fact, suddenly seems to be poised by the ice, spilling uncertainly but inevitably over various edges. Just to the right of the large tree by the water a father stands, hands in pockets, and watches his two small children testing the curious element. The children are about the same age as little Pieter and Jan would have been when their not-so-elder father painted the Census.

The skater’s absence from all copies (bar one – a recently discovered panel has the skater, suggesting a late, rectifying glimpse of the original, or an emendation by a later hand) implies that it was the father who was diverging, making changes on the hoof – inserting figures at the last minute, blotting out the vanishing point in a moment of inspiration – and the son who adhered more faithfully to the earlier version, the cartoon. There is, after all, a sensibility in copying well, an alertness to detail – one of the Younger’s guiding virtues, you could say, was fidelity. Copying is meditative and respectful work, itself a way of thinking.

If he was occasionally caught out by the odd detail it hardly matters; at some point the fractional differences collapse into the far greater mass of similarities. The census is not a record of our quiddity, in the end, but of our solidarity. Thus there is not a source of pictorial DNA – the Elder – and a series of ever-degrading replications; rather there are versions of versions all orbiting a hypothetical centre of mass (the cartoon), just as the small children of the village eccentrically orbit the centres of mass set up between them and their parents, and their parents in turn orbit the invisible barycentre which lies between them and their ancestors, and which we commonly call the community. And so on. Each of us, present or absent, exerts our own small constant gravitational tug, variable in time, hard to calculate, to take account of; but there, nevertheless, in the mass of data points, and the geometry that comprehends it.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.