I know every dog owner thinks theirs is special – but my cairn terrier really is. So monstrously wilful is this outrageous beast, so magnificently unconcerned with pleasing anyone but his fat furry self, that I often have to resort to brioche-based bribery just to get him out of the front door. Given this, the idea of working dogs has always tickled me – Wilf’s ancestors allegedly had gainful employment flushing out foxes, rats and rabbits, but in the three long years we’ve spent together he’s caught but a single, terrified mouse (apparently as much to his own surprise as ours, given the speed at which he then abandoned the poor rodent).

Like me, he’s happiest in the kitchen, so when I discovered that dogs were once a vital part of the British culinary armoury, I fancied I might finally have found the career to save him from a life of wanton idleness. Ill-suited to the vocation of a chef thanks to their lack of opposable thumbs, gastronomic discrimination and the most basic self-discipline, in the 16th and 17th centuries, canines were instead put to work turning spits.

Lowly as it may sound, this was one of the most important – if least skilled – jobs in the prosperous early modern household. Before the invention of the hot-air oven in the 19th century, meat was commonly roasted over an open fire; a method which, according to historian Bee Wilson, yields unusually succulent, flavourful results – but such pleasures come at a price. Unlike an oven, you can’t just stick the meat in and walk away. Fire is a capricious mistress, and the joint must be rotated constantly in order to ensure even cooking.

Up until Tudor times this job would have been performed by humans – generally small boys selected for their strength and their high boredom threshold (or perhaps, desperation) who laboured in cramped alcoves at each side of the fireplace, sometimes behind a wet bale of hay to protect them from the heat. Indeed, so stiflingly hot and smoky was this backbreaking work that they often toiled half-naked, covered in grime, soot and blisters – nevertheless Wilson notes in her book Consider the Fork that this was considered an appropriate occupation for the offspring of the poor as late as the 18th century.

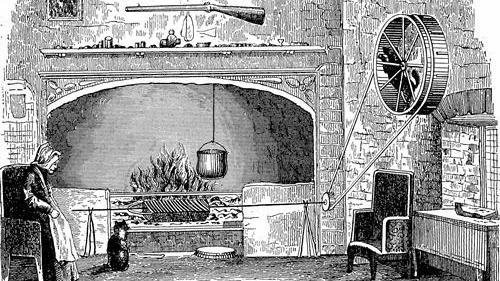

It wasn’t changing attitudes to child protection that did these unlucky infants out of a job, but a growing recognition that dumb animals were simply more biddable, and could be imprisoned in a treadmill for hours at a time without complaint. These wooden wheels were usually mounted on a wall above the fireplace, connected to the spit by a pulley system and, to maximise efficiency the dogs would often work in pairs, with one resting while the other ran. A few cooks preferred geese, which were said to be able to run up to 12 hours a day without pause, and be less troublesome to boot.

Dogs were certainly considered to have more stamina than their human equivalents however. John Caius (eponymous founder of Cambridge college) boasted in 1570 that the ‘turnespetes… so diligently took to their business that not drudge or scullion can do the feat more cunningly’. So cunningly, in fact, that they became a popular metaphor for the virtues of honest labour – one political satire of the early 18th century even casts them in the role of proud upholders of the social hierarchy, so content with their humble lot that when an agitator attempts to whip them into a strike, railing against their submissive acceptance of human tyranny, they pay him no heed, preferring to quietly enjoy their bones. Tellingly, when petted by the cook, the ‘smooth submissive cur’ quickly forgets his principles and:

…licked his lips, and wagged his tail

Was overjoyed he should prevail

Such favour to obtain.

Among the rest he went to play,

Was put into the wheel next day,

He turned and ate as well as they,

And never speeched again.

According to the Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus, dogs were often rewarded for their work with ‘a taste of the steak’, but a taste clearly wasn’t sufficient given the numerous accounts of dogs attempting to shirk their duties. A Welsh travel journal published at the tail end of the 18th century describes how at an inn in Newcastle Emlyn which employed the services of a turnspit, ‘great care is taken that this animal does not observe the cook approach the larder; if he does he immediately hides himself for the remainder of the day, and the guest must be content with more humble fare than intended.’ The little dogs were often taken to church on Sundays – not out of any concern for their sooty souls, but to be used as foot warmers – and one popular tall tale claimed that, at any mention of Ezekiel and his wheel, the turnspits would make as one for the door. Such a reaction is understandable when one learns hot cinders were often tossed in to the treadmill to encourage the exhausted dog to run, prompting a contemporary animal lover to compare the turnspit to Ixion, ancient King of the Lapiths, condemned by Zeus to roll unceasingly through the underworld on a fiery wheel for the murder of his father-in-law.

Given the labour involved, Wilf seems temperamentally unsuited to life as a turnspit, yet physically I suspect he might be ideal. Although on the Continent they used any old mongrel for the task, in their heartland, the British Isles, the animals favoured for the purpose were a distinctive type, drolly termed by that noted wag Linnaeus canis vertigus, or dizzy dog, and cited by Darwin as an example of selective breeding. So prized were good turnspits that there are records of an early Philadelphia inn keeper importing them from England to toil in his basement kitchen.

They certainly weren’t valued for their beauty: turnspits were ‘long-bodied, crooked-legged, ugly dogs, with a suspicious, unhappy look about them’ according to the Victorian naturalist Edward Jesse, though the only surviving example, imprisoned within a glass case at the Abergavenny Museum, looks like a cross between a miniature dachshund and a meerkat, with a curious curved spine that might well be the result of crimes against taxidermy rather than animal welfare. Historian Jan Bondeson is of the opinion that they would more often have resembled the modern Glen of Imaal terrier, or possibly a Welsh corgi. (Wilf, I note, does not look entirely dissimilar to the former.)

‘The Old Dogwheel’ at the Castle of St Briavel, Gloucestershire, illustrated in E.F. King, Ten Thousand Wonderful Things (1890)

This is mere conjecture, however, because, although common throughout the British Isles in the 18th century, by 1850 the turnspit dog had become a curiosity, and by the Great War, the breed had disappeared completely. A technological, rather than ethical shift seems to have been responsible for their demise: an American campaign for a ban on turnspits in the 1870s succeeded in changing public attitudes to the use of these dogs, but had unintended consequences when animal rights activists discovered goats, donkeys and even African American children had replaced them in kitchens unable to afford more modern equipment. Such concern for animal welfare was unusual in a period when few could afford to keep an idle pet for their own amusement, and dogs were considered little more than a cheap utensil, to be used, abused, and then discarded once a more efficient alternative came along.

Given the importance of spit-roasted meat to British cooking, the appearance of the automated spit turner at the end of the 16th century must have seemed like a culinary miracle, and as the technology improved in the 17th and 18th centuries, these mechanical jacks moved from luxury purchase to culinary necessity. Though there are records of turnspit dogs operating into the early 1900s, in many cases they were retained for their rarity value – there’s some evidence the last of their kind were even hired out as attractions.

With its unfortunate looks, and understandably ‘morose’ temperament, however, the breed was never going to make the transition to favoured pet. Queen Victoria is said to have kept three retired ‘turnspit tykes’ at Windsor for her amusement, but this particular royal fad didn’t catch on with her subjects, and the distinctive, bandy-legged beast quietly breathed its exhausted last just as the 20th century was getting into its stride. The real sadness is not that this poor, put-upon creature has been rendered obsolete by a machine, but that it was so little valued in its time that it’s almost as if it never existed at all. Few who enjoyed the fruits of its labours troubled to record the brief life and times of the turnspit – but let us hope they at least threw Wilf’s ancestors the odd bone.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.