However,

when, during routine evictions, I discover

alien pants, cinema stubs, the throwaway

comment – on a post–it – or a tiny stowaway

pressed flower amid bottom drawers,

I know these are my souvenirs

and, from these crushed valentines, this unravelled

sports sock, that the furthest distances I’ve travelled

have been those between people. And what survives

of holidaying briefly in their lives.

(From Leontia Flynn, ‘The Furthest Distances I’ve Travelled’)

‘I think I still hate you, Darren’.

So reads one of the entries in the visitors’ book at the Museum of Broken Relationships. This unusual museum is home to objects as diverse as a pair of fluffy pink handcuffs, a small container of tears, a prosthetic leg and a grand piano – all things that represent the end of love affairs. In 2006, after their four-year relationship had ended, artists Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišić were picking over the remnants of their life together, trying to decide what to do with the many things they had amassed as a couple. The hardest objects to divide up were those that held an emotional attachment for the couple as they felt that these things contained the energy of happier times. A germ of an idea was sown, and later, along with some objects donated by friends, the now-separated couple set up a touring exhibition of items that in some way represented broken relationships. The museum toured internationally but now has a permanent home in Zagreb, and is currently holding a temporary exhibition in the European Parliament’s Visitors’ Centre in Brussels.

This is how it works: people anonymously donate an item, they note their home town and the length of the relationship to which the object relates, and add an explanation if they want. It is these snippets of information that stop the exhibitions being a collection of random detritus and turn them into a heartbreaking, inspiring and enlightening reflection on love and loss.

Past exhibits include this axe, used by a woman to smash up her ex-lover’s furniture to reflect the sense of violent loss she was experiencing; she describes her own happiness increasing incrementally as the piles of wood grew. There is a bowl, given to a woman who explains her ex-lover wanted her to bake bread, relishing the prospect of watching her knead and pummel the dough, until she realised her bread was always a failure because she was terrified he would smash that bowl over her head in a jealous rage. There is a mobile phone, with this note: ‘He gave me his cell phone so I couldn’t call him any more.’ A blue Frisbee sits alongside this message: ‘Darling, should you ever get the ridiculous idea to walk into a cultural institution like a museum for the first time in your life, you’ll remember me.’

It’s all there, encapsulated in these seemingly ordinary and insignificant objects: the pain, the anger, the floundering, the enormity of lost love. But the museum offers people the chance to turn these emotions into a creative act, to contribute to a collective work of art, to speak their story publicly. In donating an object an individual can shift the force of that object – some things are given as tokens of love and others just come to represent a moment, but they all have a power that can be uncontrollable. I doubt that the man who bought a pair of fake breasts for his wife to wear in bed ever imagined they would one day adorn the walls in a public gallery. For his wife these breasts represented a perceived inadequacy and failing on her part, and in giving them away she regains some self-respect. In offering people a space in which to publicly take charge of their love story, the curators hope to also provide a means of preserving the happier memories held within what they refer to as ‘testimonies of bygone loves’.

Most of us have letters, fusty mix tapes or cuddly toys lurking in the depths somewhere, not relevant enough to have on display but too treasured to throw away. In storing these objects we maintain a connection to the emotions they hold while keeping them safely and unobtrusively in their liminal space. When a relationship ends badly these objects assume a greater significance, symbolising a fragment of our life that we have been unable to process fully. The break-up becomes a fault line, a crack over which we paper with memories and tokens of past happiness. The Museum of Broken Relationships provides a place in which to contemplate these cracks, the reasons love goes wrong, and the ways we deal with what the Museum’s curators call ‘brokenships’.

Perhaps we have an unrealistic expectation of love, assigning it value that could never be realised, idealising our lovers, hoping they will both ground us and fulfill us. E.M. Forster describes the contradiction inherent in any loving relationship: ‘…when human beings love they try to get something. They also try to give something, and this double aim makes love more complicated than food or sleep. It is selfish and altruistic at the same time.’ Perhaps the giving and receiving of objects mirrors these selfish and altruistic impulses.

We must be wary of seeing every broken relationship as a ‘failed’ relationship. The word ‘broken’ has different connotations: it implies something that once held a different shape, where the form has changed for the worse, but it does not necessarily follow that it has ‘failed’. There can also be a creative energy to the pain of lost love, as D.H. Lawrence knew: ‘For my part, I prefer my heart to be broken. It is so lovely, dawn-kaleidoscopic within the crack.’ We learn from these breakings, and from witnessing other people’s stories, as these strange objects once bore witness. We learn that after 18 years of marriage the most significant remnant was a box made of matches; we learn that a prosthetic limb can outlive love; we learn that things given with one intention can come to mean something else entirely. We learn that relationships never really end.

An object replaces the physicality of another person, refracting their identity. In the case of the Foundling Hospital in London, objects acted as substitutes for the mothers who had been forced, through poverty or being unmarried, to give up their babies. If a baby was accepted to the Hospital (there was a lottery system in which the mother picked a ball from a bag and if the ball was white the baby was accepted; if it was black they were rejected) the women attached a piece of fabric to the baby’s billet. These scraps of ribbon or cloth were a means of identifying the children so that the mother could reclaim her baby when their circumstances had improved. Of the 16,282 babies admitted between 1741–60 only 152 were ever reclaimed, and these fragile swatches remain as the simple markers of the love these women left behind.

An object replaces the physicality of another person, refracting their identity. In the case of the Foundling Hospital in London, objects acted as substitutes for the mothers who had been forced, through poverty or being unmarried, to give up their babies. If a baby was accepted to the Hospital (there was a lottery system in which the mother picked a ball from a bag and if the ball was white the baby was accepted; if it was black they were rejected) the women attached a piece of fabric to the baby’s billet. These scraps of ribbon or cloth were a means of identifying the children so that the mother could reclaim her baby when their circumstances had improved. Of the 16,282 babies admitted between 1741–60 only 152 were ever reclaimed, and these fragile swatches remain as the simple markers of the love these women left behind.

We give gifts to symbolise the permanence of an emotion, of love and therefore of ourselves. The giving of love tokens stretches back for centuries and reached a peak during the Victorian era. Hearts have long been used to symbolise love, the centre of the emotions, and other images such as acorns (representing growth) or artefacts like ribbons (representing the strength of love) became popular ways to express emotions. When a relationship goes wrong it is still to these symbols we turn. We are ‘broken hearted’, our hearts are ‘pierced’ or ‘diseased’, as Martha Gelhorn describes: ‘A broken heart is such a shabby thing, like poverty and failure and the incurable diseases which are also deforming.’ There is even a medically recognised ‘broken heart syndrome’ in which a lovelorn person suffers similar symptoms to a heart attack (enlarged ventricles and closed arteries). A study by Finnish scientists at Aalto University set out to map the different physical areas in which people experience emotions. The participants created sensation maps showing where on their bodies they felt certain emotions, and the results showed a startling commonality across cultures and age groups: love and happiness were felt all over the body, while sadness deactivated all body parts except the eyes, throat and chest. The study demonstrated the connection between the emotional and the physical, and just as we respond physically to emotions we can also manifest a physical reaction to objects. The act of smelling, touching and moving an object provides a means to access emotions.

In a 2006 research study using malleable ‘blobjects’ Katherine Isbister and Rainey Straus explored the emotional resonance of certain objects. They found that people universally chose the same shaped things to represent emotions, such as a spiky object to represent fear or anger. We have an intuitive sense of the form of emotions, and this can affect how we choose the objects we want to embody these feelings. This explains the omnipresence of cuddly toys as tokens of love, the softness of their stuffing and fur and evoking feelings of comfort and security. These gifts can also change us physically – our bodies adapt and change on contact with a teddy bear, our hands furl around a small hard object, an item of clothing is worn close to our skin, moving with us and absorbing our scent.

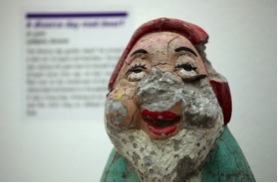

Some objects are themselves changed physically by our interactions with them. This gnome, donated to the Museum of Broken Relationships, was damaged after being hurled at an ex-husband’s new car. The accompanying description likened the arc of the gnome’s trajectory to the arc of the marriage, the moment at which it smashed into the car marking the end point. I was intrigued by this object, its face smeared with gaudy eyebrows and lashes, its red lips that reminded me of a child trying on lipstick, the milky beard and the tiny yellow spot that was perhaps once a cheek. The smashed nose and scuffs reflect the scars of a painful relationship; the jolly expression has now become a gruesome rictus grin. Gnomes are a particular and public expression of an individual’s taste and personality, but they may also hold a deeper significance. Some argue that gnomes are descended from the Greco-Roman fertility deity Priapus, who was the protector of vegetables and is usually depicted with an enormous penis. In throwing this gnome at her ex-husband’s car the woman who donated it was violently rejecting the public face of her marriage with an oddly phallic and yet suburban object, aiming it at the car which itself embodied her husband’s hubris and means of escape. I wonder what life this gnome had before – was it placed next to a pond with a fishing rod, or standing jauntily on display in a front garden? Where will its story take it next?

Objects become part of the narrative of our lives, and particularly of our relationships, playing one part as they are given to us (whether as an act of love or guilt or hope) and then another as they are discarded, or even donated to the Museum of Broken Relationships. The objects have a new life in this museum. They are as unpredictable as the feelings they represent, but for now the Museum of Broken Relationships will provide them with a home, and their stories will unravel, becoming interwoven with the narratives of love and grief of all those who observe them.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.