Green Lanes. It sounds pastoral, nostalgic, faintly utopian – like some network of ancient drovers’ tracks and holloways that endures furtively in a pocket of deep England. But Green Lanes could hardly be further from such a place: it is a drawn-out urban thoroughfare, which slices for miles through the suburbs of north London, abutted by old retail parades, housing estates and supermarkets, by ranks of semi-detached houses and parks that renounced their claims to rural retreat well over a century ago. I’ve lived near its southern limit for several years, but still find the name compelling, even uncanny. To read ‘Green Lanes’ on a road sign, and register the name’s nostalgic pull, is enough to provoke a moment of urban disorientation in which the city switches over from its familiar circuitry and starts to carry a stronger, stranger charge.

It’s towards that southern end of Green Lanes that Nick Goss struck on the source material for many of his recent paintings, themselves records of a type of urban dislocation or nostalgia, and explorations of its imaginative potential. Regularly wandering the stretch from Newington Green to Clissold Park, Goss’s eye was increasingly drawn to the road’s Turkish cafes and men’s social clubs, and to their seemingly inscrutable interiors: the bleached football posters and old framed photographs of Atatürk, the dusty national flags, domino tables and skinny pot plants, all initially glimpsed through a bead curtain or door left ajar.

Such places often have a temporary look, employing a kind of vagabond architecture in their décor and furnishing – as if they had been thrown together in a hasty, improvisational manner, just distinctive enough to mark out their loyalties and functions. But like so much of this city, these makeshift arrangements have attained an inadvertent, if vulnerable permanence. If the sparse tokens that hang from their walls must once have been pinned up as powerful symbols of a home elsewhere, they now look like images that have grown into and even under the walls’ skin, fading like old tattoos.

Goss began to venture inside these small local institutions: talking to proprietors and regulars; photographing the spaces; identifying details and patterns that might make their way into paintings; and above all sensing an atmosphere, whether intrinsic to the rooms or particular to his response to them, that he wanted to describe and interpret on canvas. This has never been a quasi-ethnographic project, an attempt to record a community that may well soon be dislodged by urban gentrification. It is something more flexible and imaginative, stemming from the artist’s curiosity about the extent to which one might engage with, and make art out of what feels foreign on one’s doorstep: about how painting might map our sympathies with strangers and their cultural memories, that is, and even push at the borders that set us apart from them.

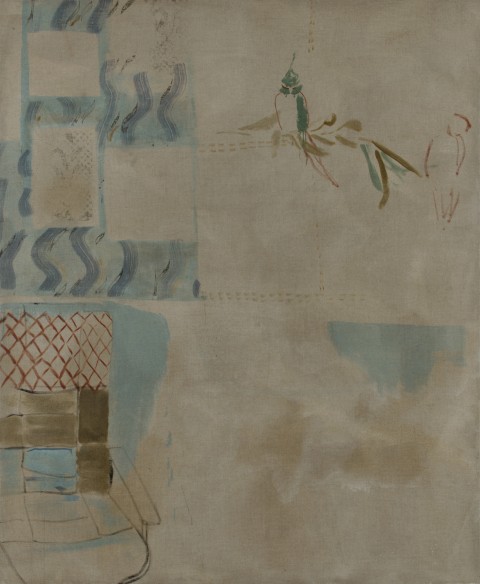

Pictures Do the Talking (2015), Nick Goss. Oil and screen print on linen backed with sailcloth, 220 x 180cm.

Such a way of looking perhaps carries the risk of a type of domestic orientalism, of exoticising what is quotidian in other people’s lives by turning it into art. But for me, Goss’s paintings are as much about exploring this apprehension as they are about representing the spaces themselves – or rather reassembling and transforming those spaces, in ethereal images that retain only a cautious hold on figuration. This attitude is partly marked by how the works develop from their photographic sources into what, at first glance, may resemble large-scale abstractions, turning from the identifiable world to images that eschew realism. But more powerful than this are the demands these paintings make on the viewer to evaluate their colliding planes and patterns, and their ensembles of solid and spectral forms. Even as they let us enter the worlds they depict, they find a way to hold us at bay.

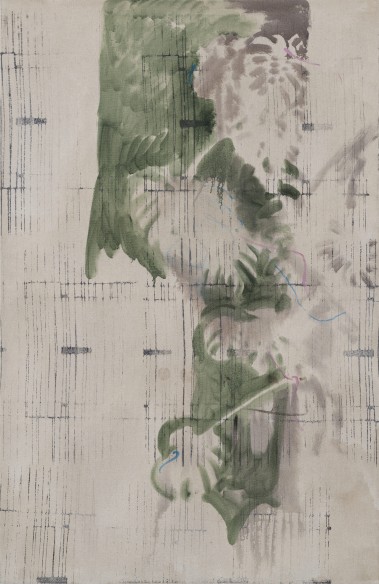

Beechwood Bureau II (2014–15), Nick Goss. Oil and screen print on linen, 210 x 300cm.

Take a work like Beechwood Bureau II: here, the curve of a tabletop indicates a room’s receding depth, but the chequered pattern that prevails in the left-hand corners of the canvas has the appearance of an upended linoleum floor that adheres to the picture plane. And then there’s that juniper-green travel poster, perhaps the most prominent single element of the painting, which presses forward what might otherwise be the rear wall of an interior against the surface of the painting. Something similar happens in Cardinal, in which an inviting easy chair hollows out a provisional perspectival space, even as the patchwork of its fabric is enlisted in the puzzle of lines and forms that dominates the left-hand side of the work. The spaces of others are often beguiling, these paintings admit, but they have an opacity that brings ethical as well as aesthetic challenges.

Kaieteur Kitchen (2015), Nick Goss. Oil and screen print on linen backed with sailcloth, 230 x 140cm.

At the same time, the real locations on and around Green Lanes have taken on imaginary dimensions in Nick’s studio, allowing him to move away from their immediate materiality and towards powerful evocations of their mood. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s concept of ‘the poetics of space’ is relevant here, at least insofar as these paintings are pervaded by a sense of how a room can carry lyrical, dream-like associations that float free from its actual appearance. Figures and objects come in and out of view, sometimes only caught with a few wisps of paint. The carefully observed pot plants in Pictures Do the Talking rest on the ghost of a table. Furthermore, recurring patterns applied to the canvas with silkscreen, such as the birdcage motif in Nonconformists, Cello and Bloom or the whorls of wood grain that run through Haller’s Azalea, Kaieteur Kitchen and several other paintings, have unmoored from the specific spaces in which the artist encountered them to become resonant refrains in his work. They are incidental details in life that have taken on an almost monumental significance in the artist’s mind; or put another way, a dwelling he has crafted for himself out of the habitats of others.

The Green Lanes paintings present a haunting investigation of nostalgia and memory, of how objects and spaces take on such variegated meanings in different people’s eyes and minds. The term ‘green lanes’ is still used to describe unsurfaced tracks or byways – routes that are detached from the managed infrastructure of the road system, and that carpet themselves with lush vegetation. In that context, it could not seem more apt as the title of this series. These are paintings that bear the imprint of other people’s journeys, but flourish with their own poetic life.

This essay was first published in the catalogue accompanying ‘Green Lanes’, an exhibition of paintings by Nick Goss at the Josh Lilley Gallery in London in May–June 2015.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.