The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) which we do not suspect. And as for that object, it depends on chance whether we come upon it or not before we ourselves must die.

– Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

If I distrust my memory – neurotics, as we know, do so to a remarkable extent, but normal people have every reason for doing so as well – I am able to supplement and guarantee its working by making a note in writing.

– Sigmund Freud, ‘A Note upon the Mystic Writing Pad’

1995. We are sitting naked on the floor about to be put in the bath. His eyes are the colour of olives and mildew, like the playroom carpet. I am twisting the dials of an Etch A Sketch. There are two white knobs in each bottom corner of the frame; the left moves the stylus vertically, the right, horizontally; both together do diagonals. Top Cat is on Cartoon Network. Our father is in rehab. Whoever I am drawing – Fancy-Fancy, Spook, Benny the Ball – my brother upends. Salomo Friedlaender, the German philosopher, said his children ‘would not like to be without their guillotines and gallows at the very least’. Walter Benjamin liked this soundbite so much he borrowed it for his essay on toys. When I scratch Conor’s eyes they feel like cut grapes.

At this time, my family is in the business of blotting out. My mother pulls us asunder with her right hand and zaps off the television with the her left. She is doing to T. C. what gravity did to my tomcats. She is turning a scratch into a blind spot. But that’s to be nostalgic about it – about the magic of toys, about the alchemy of a mother’s forgetfulness. One way of avoiding nostalgia is to figure out how the past worked. The Etch A Sketch, I now know, operates on a principle of chiaroscuro. When one turns the knob, the aluminium powder with which the screen is coated is scraped off by the movement of the stylus. It is a black art. If your brother turns your Manhattan alley on its head, hangs your trash-can kittens, the polystyrene beads blot the surface of the screen, powder it gray, recoat it with aluminium powder. The Etch A Sketch suggests that memory is a whitewash, but it is also the opposite: it is a blackout. ‘A painter should begin every canvas with a wash of black, because all things in nature are dark except where exposed by the light’ (Leonardo Da Vinci). Memory is meant to abolish chance.

In 1995, my mother mistakes forgetting for remembering. The remortgage, the loan-sharks, the other women, are botched rehearsals for a future – just as primitive line drawings at five years old qualify as art. Once a week, we visit Talbot Grove where my father is turning over his new leaf. One Sunday, I leave my hairband behind in his bedroom. There’s no time to retrieve it, because we’re already late for the bus. I worry all week that the counsellers will think he’s had a woman over, that he’s had a ‘slip’. In AA a slip is almost a relapse; but it’s not, because you realise right away that you’ve made a mistake, then you call your sponsor. In other words, a slip can be undone. There’s an old saying: ‘Under every slip there’s a skirt’. Much of my childhood was spent blaming women for how my father was. A lot of my adult life has been spent overwriting this assumption. I didn’t tell my mother about the hairband because I didn’t want to put her in mind of what she was trying to undo. The following Sunday my father gave it back.

*

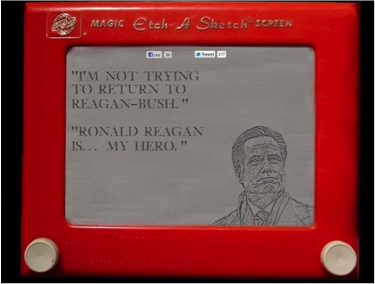

When I think of Etch A Sketches, I think of my father. And I also think of Mitt Romney. This occurs to me at a bar in New Haven, Connecticut. I am sitting with two people; one is writing a PhD on the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the other is enrolled in Yale Law. He is pretending not to notice that she is in love with him, and is talking loudly about the pointlessness of the US Primaries. Pointless, because they ought to be a dress rehearsal for the campaign proper, and because they are not. Consider their 2012 incarnation. On Mitt Romney’s 43rd wedding anniversary, Eric Fehrnstrom, his chief aid, was asked how Mitt might adapt his campaign strategy if he won the Republican nomination. ‘It’s almost like an Etch A Sketch,’ Fehrnstrom said. ‘You can kind of shake it up and restart all over again.’ Given that Romney was already perceived as too quick to change tack, Fehrnstrom probably wished he could take these words back. And so for Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum, rival candidates for the nomination, the toy came to symbolise the fact that Romney would flip-flop on basically anything. Gingrich held up the toy at a campaign event at Louisiana, and insisted that ‘You have to stand for something that lasts longer than this’. (flip-flop, n. [and adv].: orig. U.S. Polit. A change of mind or position on something; a reversal.)

Consider a few practical instances. When Romney ran for Senate in 1994, he was pro-choice, a position he reiterated in 2002. Throughout the 2012 campaign, he assuaged the Republican ranks by repeatedly calling for the Supreme Court to reverse Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that had protected a woman’s right to choose. It’s like getting the Republicans onside by trying to repeal Obamacare when, as Governor of Massachusetts, you’ve passed a health care mandate that’s almost identical to it. Romney, the Bain Capital tycoon, knew that if a product wasn’t selling, you had to rebrand it. (Likewise, after the primaries, the Ohio Art Company was prompted to sell election Etch A Sketches, in red or blue, for $19.99. The design showed a donkey and an elephant in a tug of war for the White House.) Lévi-Strauss girl tells a story about how, when the Yale Law student used to live in Cambridge, and she visitied, a waitress asked how he took his tea: ‘preferably in the Boston Harbour,’ he’d said. He would like to forget this story in the way he would like to forget that he and Lévi-Strauss girl once slept together. Now, he is a Democrat.

All of the business with the Etch A Sketch usefully suggests how, at several points in his career, Mitt Romney (like my father) tried, unsuccessfully, to become a different person; needed to erase the image of the filthy rich, cold-fish CEO, the Mormon forever adrift from the blue collars. Romney’s attempts to manufacture charisma extended as far as interspersing his speech on the eve of the Florida Primary, in January 2012, with an inert rendition of ‘America the Beautiful’.

At the Republican Convention, the following August, the leading pollster Andy Kohut said that polls showed three problem areas for Romney: likeability, credibility, and empathy. Apparently the smear campaign launched by his Republican rivals against Romeny’s inconsistencies during the primaries wasn’t easily expunged. Nor was his likeability as straightforwardly conjurable as his line on policy was moveable. This notwithstanding all attempts to humanise him: the Florida sing-song, the weird amount of detail Romney divulged about his personal history, his (albeit reluctant) release of some of his tax records, the PDAs from his wife, Ann, whose multiple sclerosis offered irrefutable proof that the Romneys were a normal family.

A story the Romneys have never been able to shake off is the one about Seamus, their Irish setter. On a summer’s day in 1983, Mitt, Ann, and their five sons, set off in a station wagon on their annual 12-hour sally from Boston to the family cabin in Ontario. Romney had custom-built a carrier for the dog which he strapped to the roof of the vehicle. All was well until Tagg, the Romney’s eldest son, noticed brown gunk running down the rear-view window, signalling that Seamus, in his aerial position, had suffered an attack of diarrhoea. Romney, a quarter of a century later, deep into his presidential bid, couldn’t lay the story to rest. A New Yorker cover from 12 March 2012 shows Rick Santorum on the roof of Romney’s car. Ann insisted that Seamus only got the runs because he had eaten some turkey off the counter prior to the journey. But the public still saw her husband, spoiled at 36, pulled over into a service station, hosing down the setter and the Chevrolet Caprice. Some shit sticks.

*

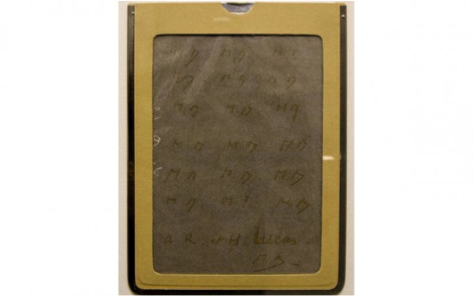

The Etch A Sketch is a mechanical descendant of an earlier model of toy – the Wunderblock. Sigmund Freud grafted a theory of sensory perception and memory onto the workings of this device when he encountered it in Vienna in 1925. Functionally simple yet conceptually complex, its two-tier structure corresponded to how Freud understood the apparatus of human perception. An upper layer of transparent celluloid adhered lightly to a lower waxen slab. When the stylus touched the upper surface, its grooves created, by this pressure, dark dents on the translucent wax layer beneath. The intrigue for Freud had to do with the fact that the marks on the wax were never effected directly by the stylus, but only through the compression of the covering-sheet. The upper and lower layers were attached to each other at one horizontal edge; by lifting and peeling the upper one away the imprints were made to disappear. Still, a faint residual trace remained on the wax beneath, and the build up of such impressions was, for Freud, analogous to a network of memories, a history of contact, the permanency of secrets.

Freud’s nexus has overtures of espionage, of privacy’s erosion, of selves drawn and withdrawn. In 1987, the LA Times ran an article entitled: ‘Magic Slate, Created 64 Years Ago, Gains New Status in an Era of Super-Sophisticated Spying’. The story goes that two congressional delegates, Rep. Dan Mica and Rep. Olympia Snowe, suspecting, on a trip to Moscow, that the US embassy was being bugged, used Magic Slates – which were not then available in Russia – to communicate. When the news broke, the manufacturers, Western Publishing, sent 2,500 slates to the State Department. In a letter addressed collectively to Ronald Reagan, the CIA, and the Secretary of State, George P. Shultz, the CEO remarked that his company was pleased to make a contribution to national security. They even toyed with the idea of designing slates with pictures of ‘Russian spies and American super-sleuths’, but decided that the operation would take a month at least, by which time ‘the whole fad could be nothing more than a Trivial Pursuit question’. Forget it. Stick with Donald Duck. Commenting on the Magic Slate’s co-optation as an instrument of counter-espionage, the vice-president of rival Etch A Sketch maintained that the older toy was not spy-proof. ‘All you have to do is put a piece of paper over it, rub it with a pencil and see what’s left,’ Chet Dahl contended, suggesting that the Etch A Sketch might serve better as a spy toy: ‘shake it and everything on the screen disappears’.

*

The thing about traces is we never quite get back to the source. As befits a palimpsest, it’s difficult to determine the exact origin of the Wunderblock or Magic Slate. The story has two versions, both involving a man named R.A. Watkins.

First version. It is the early 1920s: Aurora, Illinois. Watkins owns a printing plant in an abandoned corset factory. Approached by a man who wants to sell him the rights to a device that is handmade from waxed cardboard and tissue, and on which messages can be written and wiped out, Watkins resolves to sleep on the offer. That night, he receives a call from the jail in which the man with the device is now being held for soliciting an underage girl. The jailbird tells Watkins he’ll trade the rights to his brainchild in return for bail money. Watkins agrees, and acquires the US patent. He calls the device ‘The Magic Slate’. He does for the man what children sometimes do for each other but bureaucracies never do. He puts his past behind him. He wipes the slate clean.

The second version, as told by the LA Times on 11 April 1987, writes out these sinister intimations. In 1923, Watkins – in this version a bureaucratic caretaker – was simply killing time. Experimenting with factory waste, he attached some leftover corset plastic to the front of a wax board and developed a writing device which he brought home to his children. They adored it; he knew he was onto a winner: a dime-store toy, a cheap kick for kids during the Depression. But both versions agree about the corsets. As such, they convey a lingering sense that this toy, in all its iterations, is a little seedy.

*

For Rosalind Krauss, the workings of the Wunderblock provide a clue to parsing the Surrealist and Dadaist painter Max Ernst’s eerie early collages, produced via a technique that he referred to as Ubermahlung, or overpainting. Underneath The Master’s Bedroom, It’s Worth Spending a Night There (c. 1920) lies a sheet that Ernst found in a catalogue for children’s teaching aids in 1919. Ernst set the animations adrift by painting over the grid-like structure on which he first encountered them. The gouache paint, says Krauss, ‘is somewhat skinlike, its film seeming to have congealed over the surface of the image’. The original page beaneath becomes like the Wunderblock’s bottom layer, a memory, at once residual and blind. Curious things survive Ernst’s surrealist brushstrokes, peek through the upper surface: a whale, a snake, a table set (for whom?), a chest of drawers spiked through by a tree. Excised from the teaching aid, these are all experienced as aspects of the uncanny. There’s that primal juxtaposition: animal and bed. There’s the suggestion of taxidermy. The bear, looming large at the back of the room, comes to us out of optical perspective, just as memories can upset the proportion of the present by seeming at once too close and far away. Safer to lift the sheet, to rearrange the objects safely and squarely on the grid Ernst has obscured.

*

My brother and I were both born on 30 December; he is the hiccup in my second birthday. There are areas of his life, so it seems to me, he has lost, or that have never matured into memories. It is my fault that he has a story, perhaps because of (and not in spite of) the fact that the best ones are all his. Arson to a pink quilt (aged three); our father’s false teeth in the cistern; my uncaged canary. He doesn’t want to hear these stories, doesn’t want me to tell him, in the way that I want him to tell me, what I think they might mean. Still, we are close enough. I imagine us as Freud does the two layers of perception: ‘one hand writing upon the surface of the Mystic Writing-Pad while another periodically raises its covering sheet from the wax slab’. We are tacked together at one or other horizontal edge.

I have lots of memories of things that happened while my father was drinking, but I only ever think of two. Both concern our dogs. In the first, Conor, hair curly blonde, is wearing red wellingtons and a too-tight peach t-shirt. He has nabbed from the kitchen a packet of custard creams, and when Razor, our Jack Russell, nips the back of his hand in pursuit of one, Conor clouts him on the head with a sweeping brush. Later, when Razor died, it was Conor who found him inside-out on the road and never got over it – which is strange because I was the one who loved the dog. But we are always picking up what the other has let go of.

In the other memory, we have woken to an empty house. I get up from my parents’ bed and check each room three times before I decide they are never coming back. Then I haul Conor from the bottom bunk and bundle him, through the dark, to the back door. When I remember this night, the same sense falls through me as when I now look at Ernst’s bedroom: it is empty and full of strange things. There is the panic of converging lines and floorboards, about, it seems, to crisscross, to cancel each other out, in the same way as our parents have just vanished. I am trying to take us to the neighbour we consult in emergencies. But we are stopped, unshod, on the doormat by Lady, the setter. I have never before heard her snarl. Most people do not consider that the job of a guard dog might be to keep things in as well as outside. When my parents squelch into the yard, with a suddenness of stones and headlights, she slinks into shadow. Conor thinks that this is a lie that my mother corroborates. He turns what I say into quicksilver. A bedtime lost between his thumb and index finger; he peels the glossy sheet clear of my wax slab. Just as the layers separate, our past scatters like the grooves of make-believe. He has never seen the point in writing things down or dredging them up. Conor does not think you can give the future back to somebody through an object. To him ink is a sort of madness.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.