Author Archives: Julian Mills

Peter Scott

Close to Home

21st November 2013

The 6th November, 2001 is not a day in which history is especially interested. But those who watched Fox in the US that evening might remember it. The first episode of 24 had been put back so as not to air too soon after 9/11; by 11/6, America was ready to meet Jack Bauer.

Kiefer Sutherland’s flawed hero will be back on US TV screens soon, after a first run of nine years and eight series (one was lost to a writers’ strike). Sometimes he worked for the US government’s fictional Counter Terrorism Unit (CTU), sometimes alongside it, and sometimes against it check it out. Though conceived and part-written at the beginning of George W Bush’s presidency, before 9/11, the show was explicit in its attitudes towards the wider world from the start, and quickly found that the changed climate into which it had been born could be assimilated with gusto. 24 was a series about America, about men and heroes, about threats from within and without, and about the effectiveness of guts and force in fixing what soft power and negotiation could not. As the bombs rained on Afghanistan and then Iraq, and as round-the-clock, real-time news watched, 24 seemed like a reassertion of individualistic American might, reflecting a belief in the power of people (or one particular person) to take matters into their own hands and, in so doing, solve the world’s problems.

The first four seasons were the best, and of those, the second season stands out (though the third sees Jack operating throughout while suffering severe heroin withdrawal, and at various other times he survives heart attacks and death). This was must-see television, ambiguous in its threats and relentless in its individualism. The US government cannot be trusted, though the President is a good man. The terrorists look as if they will turn out to be Muslim extremists sponsored by the governments of ‘three Middle-Eastern countries’, but Jack’s faith in his own instincts sees him persevere and bring down the government itself in order to expose the truth: that the whole nuclear-bomb-in-LA shebang has been orchestrated by businessmen in the oil industry, at least one of whom has a fabulously evil English accent. Oh, and George Mason, head of CTU, flies a nuclear bomb into the middle of the Mojave Desert in order to save LA and avoid a slow, agonising death from radiation poisoning.

It’s not so much that Jack doesn’t play by the rules; rather, that the rules are irrelevant. Jack is, at various moments in 24: a drug addict, a terrorist, a hard-working officer of the law, a prisoner, a prisoner in China, a wanted criminal, a potential presidential assassin, a philanderer, a (really bad) father of an incredibly unfortunate daughter, a torturer, a bodyguard, an exiled, officially dead outlaw and a presidential consigliere. Only two things remain constant: Jack is always right; and Jack is always the man who can take the necessary action. The Bush administration allegedly thought 24 helped to legitimise some of its more unpopular actions, including torture, but if it did, it was because people had missed the point. Jack Bauer may have been a government employee some of the time, but in his actions, he was always himself. His methods were explicitly his methods, neither condoned nor often even acknowledged by the State. As an individual American citizen, the means could justify the end, and while the US establishment was struggling to catch up with events that seemed to have overtaken it, such a hero could provide a fictional blueprint for a hopeful future.

More than a decade later, Homeland, whose third season started in October, looks quite a lot like 24 from a distance. That’s no surprise: the writing and production teams overlap, and both deal with the threat of terror on US shores, employing a coincidence-led approach to plotting that often verges on the ludicrous, while relying on complicated father/daughter relationships for human interest. But where 24 was unambiguous in its ambiguousness (we may not have known what the hell was going on, but we always knew who would get to the bottom of it and that we could trust him), Homeland is a far more complicated beast. Its unknowns are Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘unknown unknowns’. The title carries a heavy burden; Homeland is the homeland of Homeland Security (created in response to 9/11), most simply, but also of a homeland reclaimed in Israel. There are overtones of fatherlands and nationalism, but more spiritual connotations too: the show often seems to be asking what defines someone’s home, whether it’s a matter of geography, of values, of faith, of family? Need it even be a place?

Jack Bauer had impeccable instincts, and it seems as if Homeland’s Carrie Matheson (a bi-polar, fantastically unprofessional CIA agent with issues and a sledgehammer-subtle first name) has the same gifts. But there is a crucial difference. Unlike Jack, Carrie can’t have the courage of her convictions. She’s sure she’s right, but she (and we) can’t be sure that she can be sure, because her mental state is so unreliable. Even when she has been proven right about something, she’s normally had to pass through various states of destructive wrongness on the way.

Carrie is no hero. No one in Homeland is a hero, especially not the war hero-cum-terrorist-cum-fugitive-cum-patriot Nick Brody, who drinks Yorkshire Gold tea, and converted to Islam while imprisoned in Iraq by Al-Qaeda. The only likely candidate is the brooding and peripheral Peter Quinn, who seems to have been introduced in season two mainly to compensate for Homeland’s Bauer-vacuum. More than 12 years after 9/11, it seems that America doesn’t do heroes in quite the same way as it used to. Homeland is a show about deflated power and stagnation, about failed overseas campaigns and a jaded domestic security apparatus. Jack Bauer could ignore the pesky FBI if he chose, secure in the knowledge that he was on the right course; Carrie does not have that luxury. The security infrastructure that was set up and enhanced to protect the country has become its own impediment, while the only individuals that can effect significant change are the bad guys, whoever they are.

Homeland’s extraordinary title sequence, which takes in Reagan, Bush mark 1, Clinton, Lockerbie, Louis Armstrong and an upside-down Obama, screams continuity, but not in a good way. The threats this version of America faces are always the same, and they are primarily psychological in nature. The jazz that Carrie loves stands for narrative progression, but also for something like insanity; different tunes punctuated with moments of wild inspiration before returning to a predictable standard line. Improvisation, in this context, is only possible within pre-dictated parameters. If Jack Bauer really does return, he could do worse than to lend the Homeland CIA a hand.

James Purdon

Underground

This year the London Underground celebrated its sesquicentennial. A hundred and fifty years, that is, since the first steam trains puffed their way beneath the streets from Paddington to Farringdon in January 1863. The occasion has not gone unmarked. Early in the year, Transport for London commissioned a set of Underground-themed limited-edition prints; the artist Mark Wallinger curated Labyrinth, a trove of unique pieces scattered around 270 stations from Uxbridge to Epping; the London Transport Museum mounted an exhibition celebrating the Tube’s tradition of poster art, which has given millions of travellers their first taste of artists like Paul Nash, Man Ray, and Edward Wadsworth.

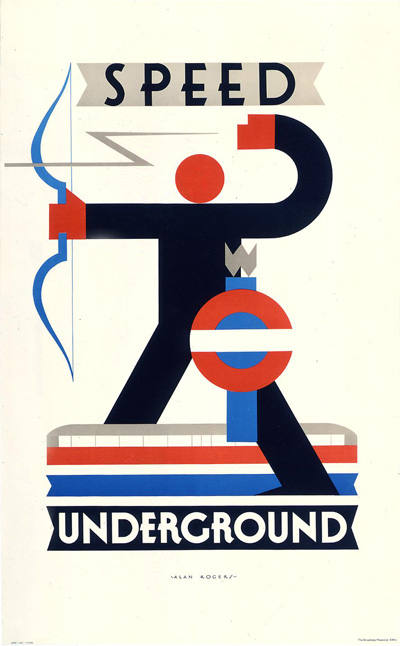

Alan Rogers, ‘Speed Underground’, 1930

Alan Rogers, ‘Speed Underground’, 1930

© TfL, from the London Transport Museum Collection

The Tube is justly proud of its long tradition of support for the visual arts, though perhaps ‘support’ isn’t quite the right word. Art has always been integrated into the fabric of the Underground. Murals, posters, and decorative tiles are everywhere, bringing creative expression into spaces otherwise dedicated to efficiency. From Frank Pick’s famous map of the system to David Gentleman’s woodcut murals at Charing Cross, the Underground has been enhanced by visual artists and designers over the last century and a half. Its artists and designers have produced the subterranean world of the Tube in ways that go beyond mere decoration.

Probably the first artworks to be associated with the London Underground, however, were sculptures. In 1928, Charles Holden – the great architectural impresario of the Tube’s built environment – commissioned Eric Gill to oversee a series of reliefs on the new headquarters of the Underground Electric Railways Company at 55 Broadway. Gill managed a team of some of the best young sculptors of the age, including Henry Moore, whose first public commission, West Wind, is the most striking of the eight panels. Far below, Jacob Epstein’s Night and Day loomed over the lintels of the building’s entrances. The public wasn’t pleased. Night was tarred and feathered by a car-load of direct-action critics. Day was denounced by right-thinking Londoners for the crime of putting too much of the male anatomy on display, until Holden brokered a compromise whereby Epstein removed an inch and a half of the sculpture’s penis. (Given the covert antisemitism directed against Epstein during much of the public debate, the act of censorship was not without irony.)

Jacob Epstein, ‘Day’, 55 Broadway, 1928-29

Jacob Epstein, ‘Day’, 55 Broadway, 1928-29

© TfL, from the London Transport Museum Collection

These works were part of the great beautifying boom of architectural sculpture between the World Wars, and the Underground led the way in adorning its stations with artworks that not only increased their attractiveness to passengers and passers-by, but lent something of their exciting, modernist energy to the identity of the Tube itself. At Uxbridge, Joseph Armitage decorated the red-brick façade of Holden’s station with a pair of winged wheels; at East Finchley, Eric Aumonier (who had been one of the artists employed on the 55 Broadway reliefs) topped the station with the figure of a powerful archer poised to shoot. Plans for another sculpture by Aumonier, a Dick Whittington figure at Highgate, were disrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War.

Eric Aumonier, ‘The Archer’, East Finchley Station, 1939-40

Eric Aumonier, ‘The Archer’, East Finchley Station, 1939-40

© Copyright Julian Osley and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

These architectural flourishes were enough to associate the Underground with the very best of British sculpture, which makes it doubly disappointing that what little sculpture has appeared on the network since the 1940s has been so forgettable. One reason there isn’t much sculpture in the Underground is that sculptural stillness – the way sculpted bodies occupy space, cuts against the timely efficiency around which the Tube organizes its operations. This is why art on the Tube tends to stay flat, in the form of graphic design, murals, mosaics, and graffitti. Even the Tube’s sculpture tends to get out of the way. Has anyone ever given a second glance to the two pieces that make up Knut Henrik Henriksen’s Full Circle in St Pancras station? Ponderously conceived, dully executed, they withdraw away from the bustle of the concourses. And yet some of the best sculptural works on the Underground are the ones nobody ever notices, not because they recoil apologetically from the bustle of mass transit, but because they have become integral to it. I’m thinking here of the sculptural works that are part of the movement and mechanism of the system itself: pieces like Harold Stabler’s bucolic scenes on the vents at Wood Green station, which summon with medievalist nostalgia the promise of a place name at odds with both the mechanised rush below ground and the urban havoc above. Even better, because it hides in plain sight, is Eduardo Paolozzi’s ventilation tower at Pimlico. Unlike Butler’s plinth, Paolozzi’s monolith makes no effort to disguise the function of the installation. With its gleaming, curving tubes, its panels adorned with cogs, cranes and satellites, it goes further than revealing an underlying functionality: it fetishises the functional, makes mechanism decorative. This is sculpture built into the operation of the infrastructure that has called it into being.

Eduardo Paolozzi, ‘Ventilation Tower’, Pimlico Station, 1982

Eduardo Paolozzi, ‘Ventilation Tower’, Pimlico Station, 1982

© Steve Cadman and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

It’s a shame there aren’t more system-sculptures after Paolozzi’s example, and a shame that Transport for London hasn’t embraced the Underground’s sculptural traditions with the same enthusiasm it has shown for easily-reproducible print works. This needn’t and shouldn’t be the case. Sculptures are a prominent and popular feature, for instance, of the Moscow Metro, where one station alone – Ploshchad Revolyutsii – boasts nearly 80 bronzes of Soviet workers and soldiers. Made to celebrate the revolutionary citizen, these days they linger on as a staple of tourist snapshots. Stockholm’s metro is packed with sculptural works: it even runs guided tours for travellers. And since the 1980s, the Metropolitan Transit Authority has been commissioning functional and decorative sculpture for the New York subway, from whimsical pieces like Tom Otterness’s Life Underground series to Alison Saar’s bronze grilles in Harlem celebrating an African-American history in which the metaphor of the underground railroad – that loose network of secret escape routes by which hundreds of thousands of slaves managed to escape to free states – has a powerful place.

Alison Saar, ‘Hear the Lone Whistle Moan’, Harlem, 125th Street Station, 1991

Alison Saar, ‘Hear the Lone Whistle Moan’, Harlem, 125th Street Station, 1991

Posters drew Londoners into the Underground by extolling the sights and sounds of the city above; murals made their experience beneath the streets more exciting and attractive. But sculpture, the articulation of bodies in space, could be the art that speaks most powerfully about the experience of the Tube-linked city. For this vast, 250-mile, three-dimensional filigree hewn from the mud and clay of the city is nothing if not sculptural. This magnificent, maddening time-and-space machine, begun 150 years ago, has tuned a million travellers to its own intricate rhythms more successfully than all the works of marble or bronze in all the galleries of London.

Clash of Clans Online Hack and CheatSusanna Hislop

On Vision

I’ve got one party trick. True, I can mildly impress a limp reveller with my hyper-mobile elbows, I can fit my entire fist into my mouth, and once I nearly met my (suffocated, messy) end during a self-initiated bet about whether I could do the same with an entire box of Crispy Crème donuts. But really, I’ve got one party trick. A real blinder. Find me someone in a pair of glasses – much easier today amongst my gently fashion conscious, 30-something friends than the enviably Disney-eyed companions of my schooldays – tell me their prescription and I’ll take that pathetic minus number, see it, and rocket it mathematically skyward: I have worse eyesight than 99 per cent of people I ever meet.

I wake up and what I see is light and colour and the memory of what my sighted self knows my bedroom looks like distorted into an approximation of reality. I wonder if this is part of what makes it so hard to get up every day. I get out of bed, remember my way around the bedroom and the bathroom (as we all do at night, in the dark, in those half-alive hours of habit) and head straight for my eyes in their pools of saline. Sometimes, if it’s the weekend, or a particularly hopeless day, I put on my glasses instead of my contact lenses, and rebel in the seasick world of semi-sightedness. Blurriness fractures around and into the edge of my glasses’ frames, making me feel dizzy and peculiar, as if I am occupying a different universe: a parallel, less urgent, and dimensionally-warped world.

I perch at the top of the stairs, preparing for descent. I push my glasses tighter to my face. I try to focus through their lenses without being distracted by the queasy provocations of perspective – where I live the stairs and walls are both white which doesn’t help things – but keep missing steps in the confusion, and in the end I push my glasses on top of my head and stumble down in myopic freefall, feet feeling their way down the familiar drops of wood.

Once in the kitchen I open the fridge, recoil at that sour curdling smell (still there, I cringe), and forage for a swiggable carton: even with my glasses pushed firmly back down onto my nose, I don’t attempt boiling water in a kettle. I sit on the sofa. I put a rug around me and root into its depths. I attempt to read, holding the page close to my face (reading is one of the only things I can do well in glasses, but even then, it’s a different thing altogether – I’m too close to the words and the book and the world of it, too alone); I stare at the warping wall. I wonder how long to linger in this blurry consciousness, this imperfectly rendered landscape. Sooner or later, I get tired of feeling half-drunk and go and put my contact lenses in. And when I do, the sharp shock of vision, of the world in all its clarity, stings my eyes.

Officially, I am disabled. My squashed, distended eyeballs skew my vision so much that the world has given this particular one of my incapacities the satisfying stamp of extremity. The NHS even gives me money off my glasses (or the old NHS did, the last time I bought a pair, and before what has now become the last time I ever vote for the Liberal Democrats). But impressive as this state-acknowledged disability might be to that limp partygoer (chewing at the edge of a plastic cup of cheap red wine, and weighing up their present level of soul-numbing boredom with the vague hope of pulling) it is no handicap. I am not blind. I feel blessed to have been given a daily reminder of how lucky I am, how difficult blindness would be – but I have no understanding of what it would be not to see. All I know is what it is not to see properly.

In fact I can actually see better than you close up – if I raise my palm a few inches from my face, I can see in microscopic vision. Walking to the mirror each morning is, and has been since adolescence, a fearful approach: knowing that I will first inspect my magnified pores in gruesome horror, before putting my lenses in, and pausing for a second in anticipation of the full, final confirmation of the night’s hormonal (and now also degenerative) ravages in 20:20 vision. In fact, that’s a cheap line: my sight is not at all perfectly corrected when I wear contact lenses. They can’t correct my astigmatism. Not at the minus numbers I’m on. Of course my astigmatism can be corrected in glasses, but then I have to exist in the permanently inebriated state brought on by the distractions of peripheral vision (and I am already at least two generations in to a mighty battle with alcoholism as it is). Recently, someone suggested that perhaps I should wear goggles. It is only a shame that by the time hipster goggles make it onto the just-about-to-be-gentrified streets in the way that – so very irritatingly – glasses did some time in my early 20s, I will be even further away from the requisite youth than I am now.

There has always been a lazy connection made between the bookish and the bespectacled. The geek in the corner, squinting over her favourite tome, with a whole legion of four-eyed heroes to console her: Larkin, Joyce, Piggy from Lord of the Flies. Reading, it is assumed, weakens your vision. Perhaps it does, though all the opticians I’ve ever been to have widely conflicting views on this, and it was Milton’s detached retinas, or possibly glaucoma, not his obdurate pride in reading, that spent his light. But certainly, the first day I walked into school wearing glasses – despite the fact they had desperately delusional little red bows on the sides – I saw in oh-too-crystal clarity a vision of the future that I was now consigned to: a thick-paned prison of scholarship, earnestness, and being the last one standing if anyone was ever picking teams in P.E. (it didn’t help that I was also unusually fat.)

I might not have been able to catch a ball in a playground, or glandular fever at a disco, but books and words were always mine. So I often feel like a bit of a fraud that words don’t affect me as aesthetically as they clearly do other people. It took a full GCS(Seamus Heaney)E smack of onomatopoeia to awaken my senses. I’ve learnt how to do it of course, how to hear not think the words, how to love poetry for its sounds not just its rhythms: I’m not tone deaf to the beauty of language. It’s just that the volume on the sensory effect of words seems turned down on my machine. Whereas the volume on colour is turned up to 11. Yesterday I walked outside and the sky was humming with a late afternoon October hue that practically broke the dial. For me the rainbow splinters into a taxonomy of emotion: give me just that particular yellow for safety; that soft green Cornish blue to think; and don’t bring me anywhere near pillar-box red. It sounds like a lie, but I once collapsed into tears in a roomful of Rothkos. And, genuinely, that was before I googled him, and realised that that’s what you’re supposed to say happened to you.

It’s a crass but often-posited theory that the sheer number of Impressionist painters who were myopic might shed some light on the nature of their work. Look! Monet, Braque, Matisse and Pissarro were all squinting at the view, Cézanne refused to wear glasses altogether! Perhaps the similarities between their work reflect not so much a shared artistic vision, as a mutual (literal) lack of it! Despite some scientific evidence that your eyesight might affect your taste in colour – myopes tend to prefer reds and browns over blues, whose short wavelengths are bent more by the optic of the eye – this theory is, in wilfully ignoring the entire history of art, almost as irritating as the common protestation that a three-year old could do a Jackson Pollock. Or the debate about whether Tracy Emin can draw. And yet. There’s something in it.

People don’t just draw differently or paint differently or indeed write differently. They see differently. It is of course a cliché, one of those oh-oh-agh-the-universe-is-MASSIVE-how-could-there-have-been-nothing-before-something archetypal realisations that really screws you the first time you ever think of it, that maybe we all see the world in entirely different colours. But it is not just colour. It is line, distance and form. In the most physical, literal and real of ways, our vision is as unique and distorted as we are. But in a world where things are often corrected – vision, spelling, wrinkles – it is easy to forget the importance of weakness - that new perspectives are often found in error. Sometimes we need to look at what we can’t see as much as what we can.

I once had a furious row with someone describing some work a photographer friend had been doing teaching blind people to take photographs. She laughed in an ugly, dismissive way and ridiculed the notion altogether. What was the point? They would never be able to see the images they produced. She could just about acknowledge the value that the experience might have for them, but utterly failed to see the wider significance it might have for anyone else. Her short-sightedness enraged me. Without their photographs we would never be able to see the way they saw the world.

I’m not sure if you always see an image anyway. Sometimes, as with a Rothko painting, you feel it. As a child my favourite painter was, unimaginatively, Van Gogh before moving on, even more predictably, to a teenage obsession with the Pre-Raphaelites. I’m not sure how much I looked at any of the paintings in question in any real sense, as opposed to interpreted into emotion their colours, shapes and idiosyncrasies. Van Gogh made things simple, wonky, but somehow safe; the pre-Raphaelites were all flushed cheeks, swirling hair, fairy tales through a satisfyingly hazy lens.

I often used to wonder which of my senses had been heightened in compensation for my lame eyesight. That old wives’ tale, or perhaps it’s true – I have no idea – that your body somehow readjusts to its own failure, inverting your weaknesses with uncanny strengths. But in the absence of my life’s experience or achievements having provided any clear evidence of this phenomenon – a keen sense of smell being the most hopeful contender – I have started to wonder if my weak vision, my greatest disability, might in fact have hidden strengths.

I have certainly not always seen my myopia in such a hopeful light. Sight, for me, is something blotted and blurred with emotion. My identity and happiness have always seemed to balance precariously on its pivot: lurching dramatically groundward that moment I walked, red-bow framed, into Mrs Cumming’s class, and seesawing brilliantly upward when years later, at secondary school, I walked into a far bitchier classroom on the first day of the autumn term gloriously rim-free. (I had, in a first flirtation with anorexia, mainly eaten melons all summer, which helped the rims around my stomach too.) But even the miracle of contact lenses brought its own dread: what would happen when I first had sex: would I keep my lenses in? Would I sleep in them? How could I possibly stay the night with a boy and expose him to the painfully unromantic nightly contact lens routine – this was before the days of all-in-one solutions, when I had to perform nightly bleach-based ablutions – or expose myself to the terrifying obscurity of a morning in an unfamiliar bed.

I am very, very glad of my contact lenses. Survival would have been virtually impossible for me as say, a 12th-century peasant – one of my frequently imagined fantasy scenarios – let alone in the audition rooms of the 21st. I am glad of my glasses too. I just wish that their milk bottle lenses shrank my eyes a little less pin-sized so I could jump merrily on the vintage frames bandwagon. But I am also glad of the peculiar, troubled way these squashed eyeballs see the world. I’m not putting a laser anywhere near them.

A friend of mine once astonished an optician who discovered that she had been walking around for years utterly ignorant of her severe myopia. Even after he had corrected her vision, she often didn’t wear her new glasses. She just preferred the world without them.

Dan Stevens

Invisible Watch

Whatever happened to my invisible watch? I can't have lost it. I don't remember a day when it disappeared. Was there a time when I still wore it underneath my Swatch watch or Casio? Is it buried at the back of a drawer; or in storage somewhere, wrapped around a much-loved toy? I have rifled through the pockets of old coats but it is not to be found.

How long have children been wearing invisible watches? I certainly had a very fine one when I was young, and I remember it being pretty advanced. Children have been nattering to invisible friends since conversation began, but the invisible watch must have been a far later development. I bet some children had invisible pocket watches.

Now, of course, watch-like devices that promise to bring all the functionality of a smartphone to a tiny screen on your wrist are beginning to take hold in the marketplace. The CPUs are around 800 MHz, with onboard storage of 4GB and 512 MB of RAM – far faster and fitter even than the tired, old laptop computer on which I wrote all my college essays. Tech giants are patenting various 'curved screen' concepts, which will bring the gadgetry prophesied in the original Star Trek into being and shift our interaction with and our physical relationship to technology one step further. There's no going back: we're fusing.

Wrist-wear seems more palatable than, say, the spectacle of Google Glass, which has yet to permeate our culture. Glass’s limited availability and high price tag, coupled with its distinct aesthetic, has seen it only taken up the initiated - the 'gluminati', if you will, or 'glassholes', as they're mostly known. You would hope that the first wave are beta-testers - developers who might broaden the scope of the eye-mounted hardware - as opposed to brash, gloating tech-junkies, in it for nothing more than exclusivity or the crude sense of feeling somehow more 'evolved' than their fellow man.

~

Which came first: the imaginary chicken or the invisible egg?

The anthropologist Hugh Brody talks of a tribe that to this day gathers every morning around the community’s children to listen to their dreams: all of them. The adults claim not to dream themselves; that their dreamspace in inhabited by and for the children. The realm of childhood fears and fantasies, their demons and delights, thereby becomes embraced by every member of the tribe as they go about their day and consequently the fabric of the communal psyche is strengthened.

In data-fying and codifying our reality to the extent that we preempt, distract and control the minds of our young, and ourselves, have we ceased listening to the dreams of our children? What value might lie there, in the beauty and magic of a pre-conscious age of pure being and knowingness, where alternative realities can be perceived, as we trundle ever-closer towards the precipice of economic and ecological disaster? A collective dreamspace could be a beautiful resolution to big problems.

~

It is days before my daughter's 4th birthday. We have been chasing pigeons in the square, sweetly aggressing the simple birds before her class begins. As she skips up to her teacher she flashes her wrist with a dramatic swish.

'Wow! What's that?' the teacher says, perceptively.

'It's my invisible watch!' she says.

A memory burst and tripped my heart as I caught a glimpse of her new wrist-wear: it is beautiful. It doesn’t tidy her bedroom (yet) but it does make butterflies fly.

My son recently turned one. He's not yet old enough to have an invisible watch, though he's developed a keen appreciation of my old-school, wrist-mounted timepieces, which no doubt I will one day bequeath him (in a rose-tinted ceremony under an old tree, I picture). He will grow up in a world where tiny wrist-computers will be a matter of fact, not fiction. Every day, now, I look at his chubby, little wrists with the disappearing crease line that made it look as though his hands had been screwed onto the ends of his chubby, little arms, to see when (or if) his invisible watch will indeed appear.

In acquiring one of these new watches (and let's face it, I'm going to, aren't I?) am I denying him the untold pleasure an invisible watch can bring? Am I bulldozing his dreamspace? Or am I raising the bar: showing him the now and sending his mind racing into the future, planting him and his sister firmly in the next generation? What functions might their watches enjoy that will surpass mine? How might their dreams shape the future?

With every digital minute that clocks by on my wrist the technology dates, requires updates, and falls behind into the past and into that ever-swelling landfill of obsolete hardware; abandoned myriad bytes of images and memories and the music of our youth, lost in the forlorn forests and fields of decaying circuitry. My daughter's invisible watch, however, is the very state of the art. Its use and design updates instantly, automatically, as required to fit the moment and scenario. (Now it can change traffic lights. Now it shoots flame.) Her watch is a part of her, it is hard-wired to her imagination: its creative thirst for progress makes it completely human. It cannot break and it makes her happy. It is priceless. I look at her watch, I listen to its ticking and I feel the present moment: the time is now. It is whatever we want it to be.

Digby Warde-Aldam

Petrol Stations

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

Do you drive? I do not, cannot and will not, but my borderline phobic attitude to the motor car exists in tandem with a genuine, epicurean love for the smell of petrol; just as the olfactory bang of frying garlic hits me with Pavlovian ravenousness, the heady, metallic stench of a petrol station forecourt immediately renders me helplessly vulnerable to the catchpenny tat in the shop. Long car journeys punctuated by filling stops have caused me to invest in copies of magazines I don’t read, CD compilations I will never listen to and truly rebarbative wraps that bear as much resemblance to their advertised ingredients as I do to Lewis Hamilton. In a city, I can resist the onslaught of garish promotions, false economies and super-sized chocolate bars (‘£1 with any purchase!!’), but out at the oases of the A1 and the M4, I’m helpless against the diktats of the convenience store subliminal. As Half Man Half Biscuit put it in their typically facetious single ‘24 Hour Garage People’:

I’ll have ten KitKats and a motoring atlas

Ten KitKats and a motoring atlas –

And a blues CD on the Hallmark label,

That’s sure to be good.

Yeah, right. This litany of rubbish says it all for the British motorist’s consumer opportunities. Yet despite their subtopian architecture, the aforementioned mediocrity of their secondary wares and the faecal stench one encounters if forced to use their facilities, petrol stations hold many associations for me. Most of my childhood memories involve seemingly interminable car journeys between London, Edinburgh and what you might forgive me for calling the Northumbrian outback. We drove abroad, too, once all the way from Dunbar to Barcelona, via London, Troyes and Marseille. I don’t remember what, if anything, we actually did in any of these places, nor do I have much recollection of sitting in the car; in fact, my own distinctly non-linear childhood narrative consists almost exclusively of stopping for lunch in motorway service pitstops.

In Britain, we tend to think of petrol stations – if we think about them much at all – as rather sorry places, sad clusters of concrete and glass flogging off fuel and Heat. Searching for examples of such garages in film and literature, I emailed almost everyone in my address book for suggestions. The response that came in only convinced me of this: ‘What about Alan Partridge? He hangs out in a petrol station’. North Norfolk’s favourite son notwithstanding, my enquiries revealed that the British canon throws up precious few garagistes; I can think of Scott Graham’s profoundly depressing film Shell, set on a small garage in the Highlands where an innocent teenage girl and her epileptic father pump out their lonely living; there is Ballard, of course (though not as interestingly or comprehensively as one might reasonably expect), and Chris Petit’s remarkable 1979 road movie Radio On, in which the protagonist arrives at a very basic petrol station somewhere between London and Bristol where the filling attendant is played by – of all people – Sting.

American lore, though, puts the petrol station in an altogether more exalted position. There is nothing left to say about the Americans and their cars or about the Americans and their oil that is not already a cliché, but the simple fact is that if you’re going to travel the Big Country, at some point you’re going to need to top up the gas. From the immiseration of the Grapes of Wrath to the frontier romance of Edward Hopper’s Gas to Kerouac’s On the Road through to Easy Rider and the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, the filling station – preferably isolated and ever so slightly fly-blown – has become a favourite hangout for American cinema, art and literature.

As a venue for an action movie showdown, it is bettered only by the nuclear reactor, the very steep cliff and, of course, the White House. Should the camera focus on a petrol pump for more than a second, the viewer knows precisely what’s coming - the only doubt lies in whether or not the pyrotechnics unit can make the inevitable Ka-Boom sufficiently impressive to keep the teenage destruction junkies happy. In The Birds, Hitchcock slipped in a particularly nail-eroding tracking shot of a fuel leak puddling its way slothfully towards a man lighting a cigarette with a match, setting the precedent for copycat scenes in everything from Robocop to Zoolander to Breaking Bad.

Explosions aside, the attractions of the gas station to American artists are obvious. For starters, it’s a ubiquitous road trip image in a landscape where one can drive for hundreds of miles without seeing any other sign of life. Beyond this, if we are to accept the car as a symbol of personal freedom, then the petrol pump is a corresponding signifier of the limits thereof. Given that its primary purpose is to distribute a fuel that has ignited wars and brought down governments, it’s a powerful political image, too. One thinks of the endlessly repeated footage of the 1973 Oil crisis, automobile queues snaking miles back from the forecourt a neat metaphor for the sudden collapse of post-war prosperity.

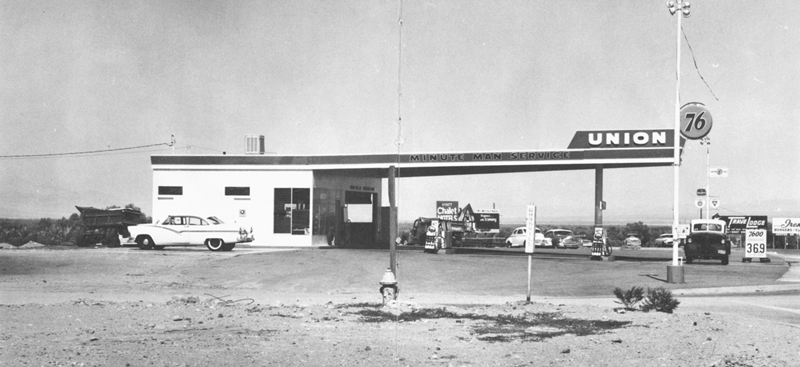

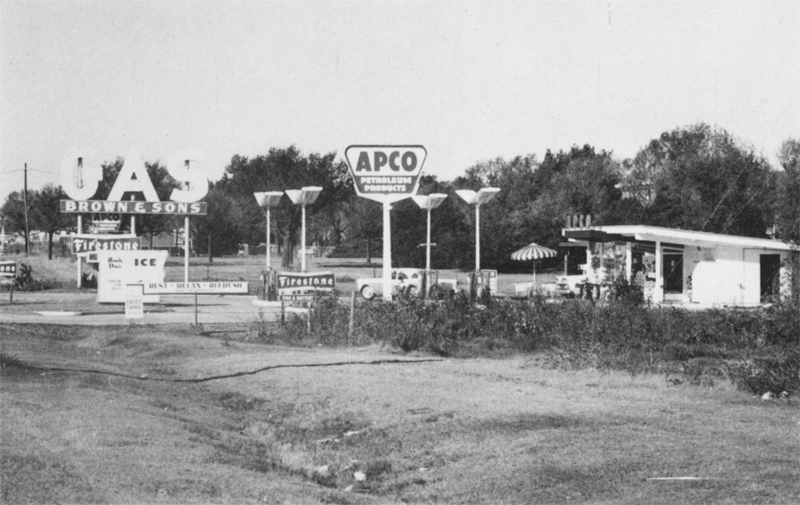

[caption id="attachment_2671" align="aligncenter" width="800"] © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

When Ed Ruscha compiled his 1962 book Twentysix Gasoline Stations – perhaps the most important demonstration of the petrol station’s significance in the index of American iconography – he was struck by the way that over a relatively short period of time, petrol stations had blended into the highway landscape:

On the way to California I discovered the importance of gas stations. They are like trees because they are there. They were not chosen because they were pop-like but because they have angles, colors, and shapes, like trees. They were just there, so they were not in my visual focus because they were supposed to be social-nerve endings.

Ruscha was identifying precisely the sort of liminal space Marc Augé wrote about in Non-Places. More than the airport or the supermarket (the former has at least a suggestion of glamour, the latter connotations of social class and spending power) the petrol station is perhaps the ultimate articulation of a ‘Non-Place’, an anonymous point of transit where ‘no lasting social relations are established’.

[caption id="attachment_2670" align="aligncenter" width="800"] © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

In spite or because of this, it still holds a strange fascination. The lack of any immediate characteristic is, I think it’s reasonable to claim, one of the principal reasons why the aforementioned artists, writers and film-makers chose to use the petrol station as a setting. Ruscha described his book as ‘a collection of readymades’, and delighted in the way its identikit reproduction echoed the anonymous proliferation of its subject matter. Similarly, Louis Aragon pontificated at length about the symbolism of the petrol pump in Le Paysan de Paris. Writing immediately after the First World War, he saw the filling station and its pumps as totems of modernity:

… the petrol pumps sometimes have the look of the deities of the Ancient Egyptians or those of warlike, cannibalistic tribes. Oh Texaco motor oil, Ecco, Shell, such great inscriptions of man’s potential! One day we will cross ourselves before your springs, and the youngest amongst us will perish for having stared at the nymphs in their naphtha.

The anonymity of mass production, mechanisation and – forgive the anachronism – globalisation, was then a rather exciting and utopian conceit. Whether or not Aragon’s pronouncements can be read as ‘prophetic’ (and I rather suspect they can’t), they had some effect on Walter Benjamin, who nodded to them in the title of Tankstelle (‘Filling Station’), the first part of his essay Einbahnstraße. In this short segment, Benjamin created a surrealist-inspired simile that compared the practice of literature and philosophy to industrial mechanics, equating educated opinion with fuel (‘one does not go up to a turbine and pour oil all over it’) and, turning the figurative language back into a tangible argument, praised the way in which new machine technology allowed for the rapid proliferation of ideas and knowledge.

[caption id="attachment_2668" align="aligncenter" width="800"] © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.[/caption]

From Alan Partridge to academic discourse, we’ve projected a lot of associations onto the canopy of the petrol station, enabled principally by the very fact that it is so demonstrably unremarkable yet at the same time so admirably utilitarian. For a catchier conclusion – albeit one that doesn’t quite scan – look to Welsh Britpop group Super Furry Animals’ hit ‘Herman Loves Pauline’:

Down the 24 Hour Garage,

Or any service station,

I lead my life in a quest for information

Practical advice for the modern pseud. But, sadly, I don’t drive.

Dorothy Feaver

We Are Now Beginning Our Descent

‘If you’re gonna spew, spew into this.’

Wayne’s World (1992)

It was one of the first times I’d flown, and my delight in the mountain tops and puffs of cloud through the window was disrupted when another child across the aisle started choking on her own vomit, precipitating a nose-bleed. Stewards dashed for entertainment packs as adjacent passengers dipped into the pouches of the seats in front of them and whisked extra sick bags over to the girl’s father. Too late – there was red gunk everywhere – but the dad put a sick bag in his luggage, so they could laugh about it later, I suppose.

It seemed that air passengers had the edge on car passengers. Mile-high puking rang alarm bells, won the kindness of strangers and elicited specially designed paper products; carsickness, as I knew from many a journey in the family car, required that parents throw in a couple of old towels in readiness for the inevitable. My sister and I, how we dreaded the ‘Joyride’ packet of travel sickness tablets, with its toothy pin-up boy: although the pink pills tasted nice, they were a guarantee of hours in the car ahead – and they never worked. Towels turned wet, grainy and cold by journey’s end.

The airsickness bag has just a thin plastic lining separating it from a paper lunch bag, but it is prized by collectors. Their decades’ worth of artifacts point to a dispersed, international subculture and present a droll version of aviation history, from military development, to the rise of civilian flights, the growth of budget airlines and a world where the internet has brought everything closer. But anecdotally, I never hear about airsickness any more and so too sick bags are increasingly invisible on plane journeys. While this is something for which most people would be thankful, for a few, it is cause for concern.

This article is written at a point when the design and production of unique airsickness bags is decreasing and seeks to touch on the implications of this star in the descendent. It takes its cue from the salutary scene in Wayne’s World, where Wayne and Garth discover their buddy Phil in a bad way:

Wayne: ‘Phil, what are you doing here, you’re partied out man, again.’

Garth: ‘What if he honks in the car?’

Wayne: ‘I’m giving you a no-honk guarantee.’

Garth, doubtful, has the alacrity of mind to pull out a tiny crumpled Dixie cup from his breast pocket and offer it to Phil. If the receptacle is hopelessly sized for the job, the gesture protests that there is no such thing as a ‘no-honk guarantee’.

~

An ancient condition, motion sickness has proliferated as our travel options have increased. The very word ‘nausea’ is derived from the Greek naus, meaning ‘ship’, and the more we try to escape our confines, the more our landlubber condition is emphasised, from seasickness through to space adaptation syndrome or virtual reality sickness. It is this realistic detail that makes H.G. Wells’s War in the Air (1908) so much more palpable: ‘For a time he was not a human being, he was a case of air-sickness.’

The main hypothesis for motion sickness is ‘sensory conflict theory’. Roughly speaking, the fluid in the semicircular canals of the inner ear conveys three bubbles, which report orientation and motion to the brain; if the inner ear signals to the brain that you're moving, but your eye says that you're sitting still (according to the immediate environment) it’s a recipe for nausea. Among remedies, there are the bracelets that apply pressure to points on the inner wrists; medication, which has side effects and is therefore discouraged for pilots; and common sense, which suggests avoiding heavy boozing, wearing loose clothing and eating something light and dry before the flight so your stomach is neither too empty nor too full. Failing all that, you could try ginger tea, although in fact the only way to completely avoid motion sickness is to avoid travel altogether.

Sick bag aficionados are rarely the avid travellers that their collections might suggest. Like stamp collections, they serve as signposts to places that remain figments of the imagination. They are often the result of collaborative effort, rather than the trophies of individual travellers and bags might be sourced from aviation collectibles shows or purchased on Ebay, but are more often swapped and traded between peers or donated by well wishers. ‘There are really only a hundred of us who collect seriously’, says Steve ‘Upheave’ Silberberg, who ranks his collection of 2,422 bags (at the time of writing) in the top ten, and who was so generous as to open a window for me to their world. ‘Sometimes, people who have been collecting surreptitiously send me their entire collections when their wife tells them to get rid of it.’ Compare this to stamp collecting, the ‘hobby of kings and the king of hobbies’, whose popularity still rages today, with millions of devotees, celebrity names, associated societies and publications. In the shadow of their more illustrious stamp-collecting cousins, sick bag collectors amount to a small tribe of postmodern philatelists.

Any successful collection of stamps or sick bags, however, will have in common the combination of accumulation with arrangement. The nineteenth century publication The Stamp-Collector's Magazine judged it expedient to publish a defence of their shared pursuit, which includes this description:

Its study also tends to induce a habit of observation of minutiae and order, the many differences of detail requiring to be carefully noted, and systematic arrangement being necessary in order to exhibit the beauties and the uses of stamps. (1867)

Sick bag collectors, like stamp collectors, conform to a mutually generated code for the systematic presentation of the bags. Bags should, of course, be unsoiled – neither wrinkled, folded nor stained. Further to this, German fan Wolfgang Franken, who has managed ‘Die Welt von Tuten’ since 1996, provides a roll call of 49 prominent ‘bagologists’ and an overview of their standards:

The modern collector doesn't use shoeboxes to keep the bags in. The bags are put in transparent folders, and neatly filed in some kind of archive. Keeping an overview of one's collection is done with a computer. Tables with date of acquisition and other data are kept about the bags. As every now and then airlines change their bag designs, there must also be a system for keeping track of this: bags with or without a logo, variations in colours, what material is used (paper, card, plastic, etc), closing mechanisms for the bags, and so on. (Airsicknessbags.de)

Online collections are usually sorted alphabetically, according to airline, country or region of the world, often with multiple editions from an airline; sometimes with an indication of whether the collector has doubles of a bag for trading. For bagologists, the emergence of the internet has been instrumental, but beyond the practical advantage of online bartering, sick bag websites serve as museums for treasured hauls. Bruce Kelly, of ‘Kelly’s World of Airsickness Bags’, hails from Alaska, and came to ‘airline art’ through spending so much time on flights. He says: ‘I briefly considered collecting safety cards but instead zeroed in on what I considered were the often over-looked and under appreciated little air sickness bags.’ His collection of 5,941 bags increases at a monthly rate of around 20 bags: it’s a commitment.

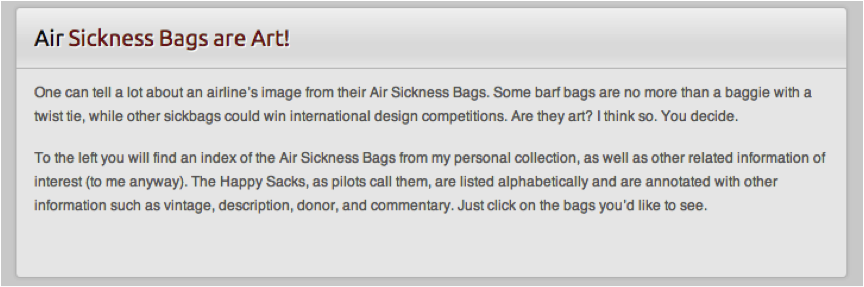

[caption id="attachment_2640" align="aligncenter" width="865"] Home page, Kelly’s World of Airsickness Bags, Kellysairsicknessbags.com[/caption]

Home page, Kelly’s World of Airsickness Bags, Kellysairsicknessbags.com[/caption]

Kelly admonishes himself for being ‘computer illiterate’ but what is remarkable about his and his fellow collectors' online museums is their shared organisational principles and aesthetic choices. Their styling reflects the rise of the web as a free-for-all. ‘Rune’s Barf Bag Collection’ (Sicksack.com) is a prime example – a static gallery imposed on a bitmap background of blue sky and white clouds. Rune Tapper’s obsession with sick bags was in fact a way of dipping his toe into the internet in 1993. The Swedish radio engineer, who also collects obsolete computers, was only trying to make his webpage stand out by posting curios, but his collection of five bags inspired emails from all over the world offering to augment the site. He credits donors with a hierarchical thanks page – from ‘First Class’ through to ‘Tourist Class’ – and he, like many others, has a page devoted to swapping.

Steve Silberberg, the self-described ‘curator’ of the Air Sickness Bag Virtual Museum (Airsicknessbags.com), graduated in 1984 from MIT with degrees in computer science and electrical engineering and has never even travelled outside of North America: his interest in sick bags was made entirely possible by the Internet. His museum has a sober maroon and grey colour scheme, indicating a more serious, self-aware approach. The collection is fully searchable and offers a wealth of links to other collectors, online exhibits, and to ‘Barfbags’, a forum for collectors counting 90 members. A humorous man, Silberberg’s interest is whipped up by bags that do more than act as a receptacle, and extends to examples from beyond the airlines: ‘I guess the seventies were a golden age. Big gaudy designs with games such as tic-tac-toe, Gin Rummy scorecards, “X & O”, pictures of dogs (use as a doggy bag) or even a kangaroo. I’m starting to get weepy...’

Danny Calahan, from Sydney, has been collecting sick bags since 1988 and his dedication was the subject of an actual exhibition, ‘Fully Sick’ at the Museum of the Riverina in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales in 2011. The 200 specimens in the show could be traced back to Calahan’s first memento, but he was quoted in The Australian with a warning tone: ‘I don't collect anything else, once you enter the world of air sickness bags, anything else would be second-rate.’

The Guinness World Record holder for most airsickness bags does not subscribe to the open values shared by many other collectors. Niek Vermeuler, from the little Dutch town of Wormerveer, set out on his wacky pastime somewhat cynically, in order to win prizes. His 40 years in the game paid off, with over six thousand bags from 1,142 different airlines in 160 countries, but speaking in 2011, he struck a doleful tone: ‘I’m old now and my medical situation is best described as “the time is coming”. So I’ve started looking for a successor to take over my collection.’ Vermeuler doesn’t take into account that the time is coming for airsickness bags too: he will be looking for a caretaker rather than a successor.

[caption id="attachment_2641" align="aligncenter" width="864"] Home page, Welcome note from Steve ‘Upheave’ Silberberg’, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

Home page, Welcome note from Steve ‘Upheave’ Silberberg’, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

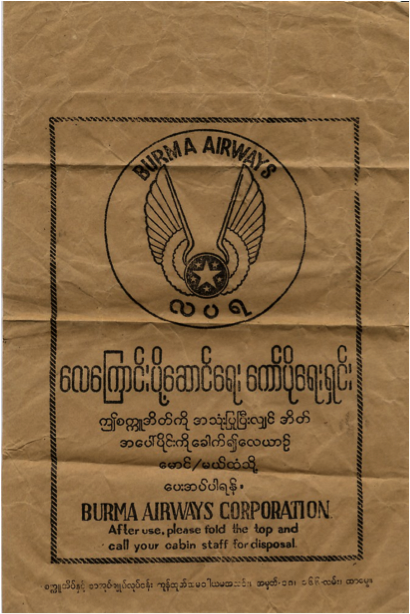

[caption id="attachment_2642" align="aligncenter" width="410"]

Burma Airways (1977), ‘Excellent old bag that’s paper and not even lined, from a country that no longer exists.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

Burma Airways (1977), ‘Excellent old bag that’s paper and not even lined, from a country that no longer exists.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

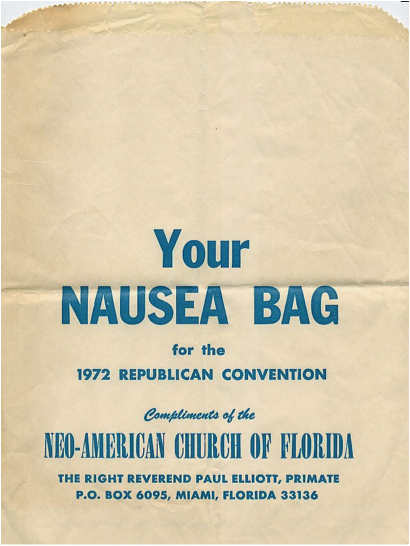

[caption id="attachment_2643" align="aligncenter" width="410"]

1972 Republican Convention (1972), ‘A beautiful museum piece -- the essence of what this collection embodies.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

1972 Republican Convention (1972), ‘A beautiful museum piece -- the essence of what this collection embodies.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com[/caption]

~

The outlook for Kelly, Tapper, Calahan, Silberberg and even Vermeuler is not good. Many airlines have stopped branding their bags, carrying plain white ones instead. I asked Silberberg, as a man on the front line, about the impact on his collection. ‘In the States anyway,’ he says, ‘airlines don’t like to brand their bags anymore. They seem to want to distance themselves from the possibility of nausea during flights.’

Up until the 1950s, queasy air passengers made do with card or waxed paper envelopes. So while inventor Gilmore Schjeldahl is usually first credited for building Echo 1 (launched by NASA in 1960, it enabled the first satellite telecommunications) his expertise in plastics and adhesives bore fruit earlier in his career. Back from World War II, the war veteran experimented with hot knives in the basement of his Minnesota home, developing techniques to cut and seal plastic – and this resulted in the invention of a bagging machine. Schjieldahl made the first custom design sick bag in 1949 for local airline Northwest Orient Airlines, with which the fate of commercial aviation was sealed.

If sick bags have a lower profile these days, it would seem symptomatic of travellers being less sick. When it comes to solutions, the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory remains phlegmatic, saying that one of the best countermeasures for motion sickness is simply adaptation (Webb, 2011). However, the primary factor towards a decrease in airsickness since Schjeldahl’s era must be the relative smoothness of journeys. Larger jet planes make for greater stability than earlier propeller engines; we benefit from improved weather radar systems and refined air traffic control, which enables less circling; and since in-flight smoking was banned in 1998 cabin air is no longer full of cigarette smoke. Precise figures for airsickness in the general population are tricky to gather but according to NASA research, only 1–2% of the general population experiences problems on commercial aircraft (Reschke, 2008). A British study into commercial flights observed that 0.5% of passengers reported vomiting alongside as many as 8.4% reporting nausea and 16.2% reporting illness (Turner, 2000). Lateral and vertical motion was found to correlate to sickness, though to an unpredictable extent because, the study admits, this is where an individual’s psychological perception of flying comes into play.

Sick bags were once a psychological tool – the attractive designs attempting to mask the horror of being sick on board. Collector and designer Helene Silverman casts a professional eye over her set: ‘Airsickness bags need to be solid, physically and graphically: immediate identification is important’, she said in 2002. ‘They are often designed in a super-clean Swiss style so as to remind you of vomiting as little as possible.’ But just as around half of all astronauts experience nausea in their first few days of space before gradually acclimatising, it seems likely that over the last 50 years the general flying public has simply toughened up.

A death knell for the airsickness bag was sounded by Virgin Atlantic in 2004, when they ran a design competition. Far from a renaissance, this marketing ploy confirmed that the place of sick bags in the air cabin was retro and risible. Agency man Oz Dean had been running ‘Design for Chunks’ since 2000, getting designers to ‘illustrate the usually plain in-flight sickbag’. Virgin caught on, and distributed 20 of winning designs in a half-million print run. The project attracted considerable attention and the six-month supply ran out after three months due to hoarders. Riding a wave, in 2005 Virgin carried a set of four promotional sick bags for the new Star Wars movie and video game (in the noughties, numerous airlines started selling advertising space on their sick bags). Again ahead in blue-sky-thinking, Virgin produced a man-sized sick bag, printed with a five-foot deluge of self-conscious text: ‘How did air travel become so bloody awful? First they took away the meals. Then, the pretzels. And then, the peanuts. All seven of them…’ etc. It’s a hop, skip and a jump to Lydia Leith’s commemorative sick bags for Will and Kate’s wedding in 2011.

[caption id="attachment_2645" align="aligncenter" width="745"] Design for Chunks, Virgin Atlantic, 2004[/caption]

Design for Chunks, Virgin Atlantic, 2004[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_2644" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Royal Wedding sickbags: http://www.lydialeith.com/sick-bags/[/caption]

Royal Wedding sickbags: http://www.lydialeith.com/sick-bags/[/caption]

~

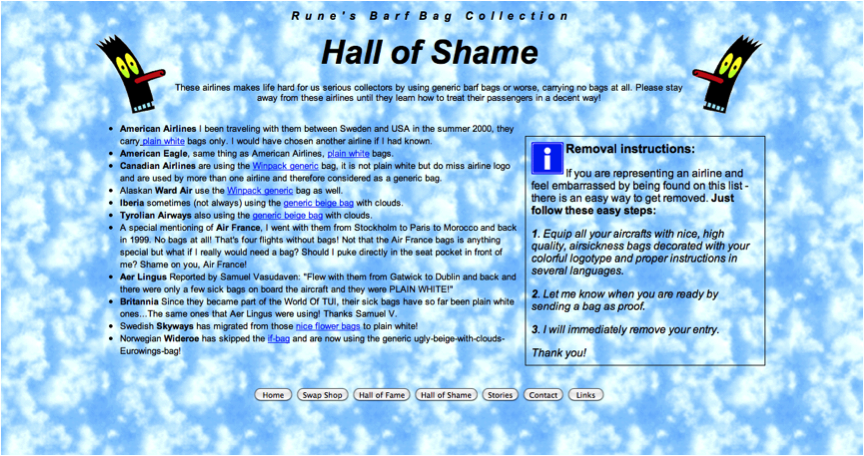

Unique airsickness bags may offer a salve to the discomfort of aviation, but, like the in-flight meals, drinks, face wipes, pens and movies, such fripperies are falling victim to cost-cutting. Helene Silverman told me that the impact on her collection has been stark: ‘As a matter of fact, it has been impossible in domestic flying to add to the collection. It has been obvious that to cut costs, bags became plain white, so sad!’ That complaint is echoed by many of her peers. Kelly envies his European counterparts: ‘It is not easy for a North American to amass such a collection as most of the airlines based on this continent including Alaska persist in using generic white bags that do not identify the name of the airline.’ Rune Tapper chimes in: ‘We are very, very upset by this. Most North American airlines now use plain white bags – it is a disgrace!’

Tapper’s outrage is concentrated in a page on his website entitled the ‘Hall of Shame’. His pet hates are white bags, generic Winpack bags and worst of the worst, no bags: ‘A special mentioning of Air France, I went with them from Stockholm to Paris to Morocco and back in 1999. No bags at all! That's four flights without bags!’ There is a certain irony to Tapper’s fury. He speaks with righteousness, as if he were making a stand for nauseous passengers, when arguably the airlines’ stinginess could be pinned on those collectors who have snatched all the samples from the aisles. For unique airsickness bags have gone the way of the Dodo.

Sick bag collections have no monetary value, but as their items become increasingly rare, they’ll glean a certain elegance from historicity – as will the websites that house them. Now the Internet is clickbait, but these sites are monuments to the early years of online pioneering, when it was the domain of the noble aficionado. They raise a toast – a Dixie cup – to a period when globalisation could be measured by a paper trail.

[caption id="attachment_2646" align="aligncenter" width="864"] Rune’s Barf Bag Collection, Hall of Shame, Sicksack.com[/caption]

Rune’s Barf Bag Collection, Hall of Shame, Sicksack.com[/caption] James Wade

Drunk Monks

Imagine this: a couple of official-looking suits roll up to your place of work, twist their ties up to 11, and demand – with no apparent good reason – that you close up shop. That’s it, they say, everybody out, lock the doors, business closed.PolVam

In the late 1530s, scenes like this would have been played out across Britain time and again. When Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries following his break with the Church in Rome, he was shutting down a lot more than just churches with bunk beds. The monasteries were fully functioning micro-economies, sustaining themselves and the needs of the local poor. The twin calls to self-sufficiency and social charity meant that the monks worked to meet all communal needs, as farmers, weavers, tailors, cooks and, of course, brewers. All highly skilled professionals and all, suddenly, out of a job.

So where did all those brewers go? The Revd Godfrey Broster, Rector of Plumpton and Head Brewer of Rectory Ales, has a theory. I went to listen to him give a talk in the Brewer’s Arms, a cosy little local on Lewes High Street, in the shadow of the town’s medieval castle. When I showed up he was drinking with a group of men huddled at the bar, though he was the only one of the lot dressed all in black with a white clerical collar. The lady pulling pints had to interrupt their conversation to remind Mr Broster that it was time to start his talk. It began with a discussion of how these unemployed monks would have sought work in the large country houses, all of which would have had, in a time before a commercial brewing economy, their own homebrew kits. This makes sense, and doubtless many monks did find their way to country houses, but there are other possibilities as well.

Some might have gone to the many taverns and alehouses that brewed their own ale, despite the fact that pious folk, like the medieval poet William Langland, looked so unfavourably on those dens of gluttony and lust. If they were slightly more interested in keeping up appearances, they could instead have gone to the big inns found along the major roadways and urban centres. Ideal employers might have included Shakespeare’s favourite boozer, the George Inn, which still survives on Borough High Street, or the Tabard Inn, just down the street, from which Chaucer’s pilgrims set off on their road-trip to Canterbury. Of course, there was always the option of just heading south and knocking on the doors of monasteries on the continent. One such house, the Weihenstephan Abbey in Bavaria, owned a hop garden as early as AD 768. It still brews world-class beer to this day.

Perhaps this latter option would have been most appealing to a master brewer, given that moving to a country home, or a tavern or inn, would have seemed like stepping down a pay grade or two. It’s easy to imagine monastic breweries as small-time affairs. But these monks weren’t brewing stingy batches in a pot over the kitchen hearth. Using an ancient overhead projector (borrowed, no doubt, from the rectory storage closet) Mr Broster showed us sketches of an abbey in Yorkshire that, according to archaeological evidence, had a brewery with a capacity of 120 barrels. That’s a lot of beer – 34,560 pints, to be exact – all bubbling away in the abbey’s fermenters at any one time. Harvey’s, the large production brewery located just down the hill from the Brewer’s Arms, currently operates at about the same capacity.

The oldest drawings of a monastic brewery come from a ninth-century account of St Gall, in modern-day Switzerland. The plans actually show three brewhouses, presumably because at the time, mash tuns and kettles were only built so large. One brewhouse was dedicated to providing for distinguished guests; another was for pilgrims and paupers, who were each given two tankards of beer per day; the third served the monks themselves, each of whom were tipping back nearly 900 pints per year. As you might imagine, these thirsty monks were putting no little pressure on their brother brewers to roll out nearly 20 barrels of beer per week, and that out of a single brewhouse.

When thinking about all those suds, don’t believe the ‘beer wasn’t as strong then as it is now’ myth. Historic recipes tell a different tale, as do medieval stories of people getting monumentally wasted on relatively small quantities of ale (as we shall see). Having paused to wet his whistle, the Reverend told us that monks in medieval England would have typically brewed three different beers, each of varying strength: a light beer or table beer, between .5 per cent and 3 per cent ABV, for washing down the breakfast porridge; a bitter, between 3.5 per cent and 5.5 per cent, to accompany a midday snack; and a strong ale, between 7 per cent and 11 per cent, for evening revelries. It’s said that Queen Elizabeth I reversed this convention (being the Queen, she could do that sort of thing), drinking three pints of strong ale for breakfast.

What did the medieval church make of all this boozing? Consider the ancient Abbey of St Augustine, a Benedictine house in Canterbury and one of the largest and most influential monastic houses in England. The standard Benedictine rule allowed for one pint at each of the regular meals. The monks in Canterbury, however, took this to refer only to pints of wine. Since beer was not expressly mentioned in the Rule, the monks reached the obvious conclusion that beer consumption should be unlimited. On average, each monk at St Augustine’s Abbey drank two gallons of beer per day.

This did not, of course, stop the monks from railing against the evils of excessive drink beyond the cloister. The taverns were particularly common targets. One 14th-century monk of St Augustine’s, Michael of Northgate, glugged his way through two daily gallons while completing the Ayenbite of Inwyt (Prick of Conscience), in which he imagines the tavern as an anti-church. In church, Michael says, God works his miracles by making the blind see, the lame walk, the mad sane, the dumb speak, and so on. In the tavern, meanwhile, a man walks in upright and comes out staggering. He goes in speaking well and leaves slurring his words. He enters in command of his wits and walks out a bumbling fool. Such are the miracles the devil works through drink.

In Langland’s poem Piers Plowman, one of the most memorable characters, Glutton, is on his way to church one day when he is stopped by Ms Betty the Brewestere, who coaxes him into her tavern for a swift half. Well, Glutton never makes it to church. He joins the tavern’s rioters in laughing, scoffing, gambling and playing ‘Lat go the cuppe!’, a call to chug the remaining contents of one’s tankard. In the course of the evening Glutton downs a gallon of ale, but this must have been one of Betty’s stronger brews. When his stomach starts to rumble like two greedy sows, he pisses two quarts, farts, staggers around, pukes in his friend’s lap, and eventually passes out, only to wake up two days later, asking for another pint.

Despite its high jinks, one might easily construe Glutton’s adventures as the invention of an especially uptight priest, given Langland’s rather one-sided depiction of goings-on down the pub. This was not necessarily the default clerical position, however. Take the 15th-century Bishop of Chichester, Reginald Pecock, on the question of how we should behave ourselves when we are given no direct instructions from Holy Scripture. Murder? Clear enough. Adultery? Ditto. Not coveting thy neighbour’s donkey? Got it. But what about necking pints? On this the Bible gives us neither ‘thou shalt’ nor ‘thou shalt not’, let alone any advice on recommended daily units. (Mr Broster pointed out that in the Old Testament the Philistines drank beer; the Jews, of course, drank wine.)

Think about it this way, Pecock says: the Bible doesn’t tell you when you should sit on the toilet, and once there, only a fool would stay seated until he found a passage in Scripture telling him when to get up. Sure, Pecock admits that brewing and drinking beer are sources ‘of whiche so miche synne cometh’, like the scandalous women who wear head-coverings made of linen or silk. However, in the absence of a direct steer from Scripture, Pecock argues that all we can really do is use something else God gave us: our faculties of reason.

The problem with stiff drink, however, is that it has a way of diminishing one’s faculties of reason. The point is made by another man of religion: the Pardoner in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Consider the Biblical King Lot, for example, who once got so drunk that he unwittingly slept with both of his two daughters: ‘So dronke he was, he nyste [knew not] what he wroghte’, the Pardoner says to his fellow pilgrims. The Pardoner then elaborates on the effects of too much drink, from unseemly leching to bad breath, before eventually coming back around to the theme of reason:

Here, though, the Pardoner is referring explicitly to wine, which makes slightly less ironic the fact that he tells his tale just outside an alehouse on the road to Canterbury, having just polished off a tankard of especially strong ‘corny’, or extra malty, ale. Let’s think about this. The pilgrims begin with a merry evening at the Tabard Inn. The next morning they hear a dirty story by the Miller who is already drunk – or still drunk – on ‘ale of Southwerk’ (presumably the house brew of the Tabard itself). Then, later on, they stop off for a tankard en route. And of course the whole point of the story-telling competition is to win a free round of food and drink back at the Tabard. Perhaps it’s appropriate, after all, that they are on their way to Canterbury, though not because they plan to visit the booze-fuelled Abbey of St Augustine, or to frequent the topsy-turvy anti-churches Michael of Northgate must have heard about (but surely never set foot inside). Instead, Chaucer’s pilgrims are on their way to see the shrine of St Thomas Becket, the martyred Archbishop who also happens to be the patron saint of London brewers.

It was Henry II who had Thomas Becket murdered, Henry III who had his shrine installed, and Henry VIII who had it destroyed. But before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was Henry VI who granted the first charter to the Brewers Guild of Our Lady and St Thomas Becket. Like many companies in the City of London, the guild was established to facilitate business and set industry standards. As both a legendary brewer and an honourable Ecclesiast, Thomas Becket was a fitting patron saint, since the Guild’s regulation of both quality and strength would have been modelled on the breweries found within England’s cloisters.

The two beers from the five-barrel brewhouse of Rectory Ales, which Mr Broster brought along for us to sample at the Brewers Arms, would have been considered mid-range brews for both the medieval guild and the monasteries. His Harvest Ale, a mid-brown, malty seasonal, at 4.8 per cent, is an orthodox interpretation of the autumn style: sweet and delicious. My favourite of the two, though, was his Rector’s Revenge, a bitter at 5 per cent. I didn’t ask the good Reverend what revenge he was exacting with this brew, but I would like to think of it as a kind of retribution towards brewers who don’t respect the antiquity of their craft. The Revenge is a dark amber ale with a thin and effervescent head. It was perfectly conditioned, beginning with a bitter fizz on the tongue and finishing with subtle notes of sweet malt at the back of the palate. As I settled in for a session at the Brewer’s Arms, I wondered what Henry VIII would have made of the Reverend’s ales. Henry VIII: the man whose 1534 Act of Supremacy arguably had a more devastating impact on brewing culture than the 18th Amendment, the law that brought in Prohibition in the United States. But maybe this is the Reverend’s revenge: a man of the cloth still brewing beer in England, nearly 500 years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Natalia Calvocoressi

61 Days

61 Days documents the time I spent last year living in an apartment in Little Italy with my friend Jessie as she created a new life for herself in New York.

Marianne Morris

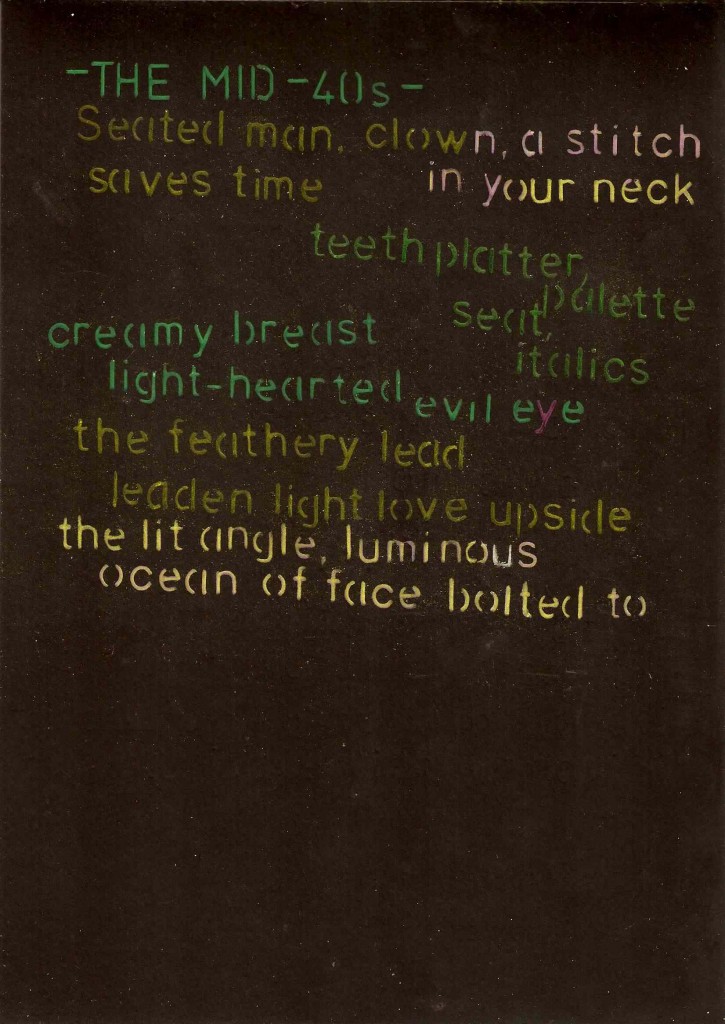

De Kooning, a Retrospective

25th January 2013

New York, 10th January 2012

seated man, clown, a stitch in your neck

saves time

teeth platter, palette seat, italics

creamy breast

light-hearted evil eye—

‘a major at forty’

ART BEGINS AT FORTY.

Only ego to take you

to the front of the line

ahead of time

where you begin born.

FORTY.

Colour in the late thirties

approaching

colour in the mid-forties he is born at the turn

of the 20th century

meaning all decades

correspond

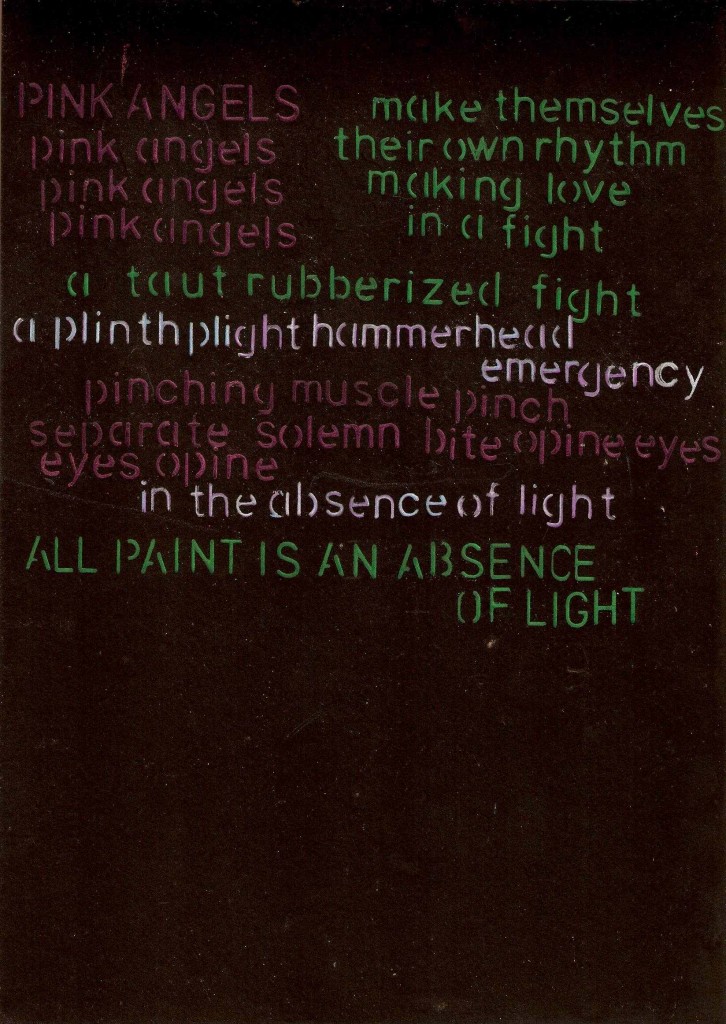

PINK ANGELS make themselves

pink angels their own rhythm

pink angels making love

pink angels in a fight

a taut rubberised fight

a plinth plight hammerhead emergency

pinching muscle, pinch

my eyes

separate solemn bite opine eyes

eyes spine

in the absence of light.

ALL PAINT IS AN ABSENCE OF LIGHT

just think, just think,

is inverted sight

Jack of all

primary goof Woman 1942

PINK LADY IS ORANGE!

I can’t fathom those

who fret over the Women of the 50s

they are not housewives and not

anatomised

atomising

a woman in the 50s

is an act of love

sun sets on her

seated, arm is a

shoulder of

tentative lamb

The figures of the mid-forties

having little to say

to the figures of the late thirties

how does colour feel

colours feel

induce feeling

shout out ME! ME!

how a colour

is a boundary

not merely a line when it isn’t a line

untitled to be nothing untrue

in 1945

a panelist of the future

I can’t talk about 48-49

nothing asks why

some tawny fox flesh hides

irrevocable black, irrevocable white

enlightenment cartoon stoop

TRIBAL GRAFFITI STOOP!

the chair interrupts

teeth in sky, engines, rockets

heroic, comic fire

crucifix borders sitting bones sky

‘sort of sexist’ says the mom

‘that’s gross’ says the daughter

Clumpy vulval pocket pants

How many times

to be women or woman and

woman and man and

man woman

pause for thoughts

break for shadow

tilt for lemon

rescue tenderly spite

LATE FORTIES WOMEN

I CAN’T EVEN GO THERE

IT’S TOO TOO EXCITING

TRIBAL VANITY FLIGHT

TURBID SPLIT THIGH

TOE TO HIPBONE THEY FLY

IN A SUSPENDED CLOUD OF RAPTURE

THAT SWINGS ABSENT SKY

then you star in her eye

then you star in exuberant eye

in Woman, 1948

OH I’M MELTING!

black milk spurt destroyed

across every straight line

I like to think of woman, 1949-

50 as how anyone feels after

spending all they have in the lines

that make body arise

through impossible trials into

tip of the arc before melting and

letting go

and how I’ve lain in bed destroyed

nothing curved but my breasts

the rest of my lavender exploded from inside

and I’m lying there, black green and white

and I’m lying there, cream in my

eyes

and a crest of red

bites at the head of the board

spitted fuchsia on lavender thighs

The Yorick, the ladder, the door of abstraction

in 1949

-50, the clown pajamas

muscular llama face, mirror

a drawing pin

soapy light

blue sky inside

Tell me—

what happens to colour in the

mid 1950s?

Colour is now the apprentice of noise—

The thing that most strikes me

about 1963 is how

suddenly light is present inside

and that paint suddenly

knows how to be light

and even before knowing it’s supposed to be Dawn at Louse Point

the sense is immediate light

Women of the mid-sixties

are trying to keep it together

in a gory enamel melt that is like cheese

like preening orange cheese

it is an utterly compelling bad moment

a recklessness not to be trifled with.

By the time you have painted

the superhero comics awesomeness

of Untitled XII,

I am alive

and you’re heralding

the future

the primary colours of dementia

the white space clearly missing things

clearly so much more than white, memory wiped

one last gush of pink in 1981

made to party with blue and yellow besides

and then primaries, white,

and the flag

by the time titles have disappeared, in 1984

you still remember flesh