I drove past Fung’s a few days ago. Of course, it isn’t Fung’s now. It’s an empty building surrounded by weeds, an ugly breezeblock shell. There’s plywood over the sliding doors, and a spindly tree, or maybe an enormous weed, waving from the roof. The carpark contains a single shopping trolley, once painted green.

I slowed the car, but there wasn’t much to see. Even the sign has come off. I remembered when we erected those letters, me and Ranjeet, with Leena below: banging them up there one by one to spell F, FU, FUN, FUNG, FUNG’S. Perhaps they rotted and fell down like that, one at a time, beginning at the end. Undoing the name.

It hasn’t been Fung’s for 15 years, but what other name could it have? Every place needs a name, or else it’s just dead space.

Of course, it was dead space before it was Fung’s. Merely a different type of dead space. Somewhere that affected life and was all the more dead for trying. And now it’s reverted to dead space again, and this time it’s properly dead. But between those stretches of dead space, there was a period of time – it wasn’t much more than two months – when there was a flowering of wonderment. I lived through the glory days.

I drove past Fung’s, and then left it behind. I could have stopped, but what would have been the point? You can stop, but you can’t go back.

*

Mr Fung took over the Superway when I’d been working there for five months. He assembled all staff outside the walk-in meat fridge and delivered a short speech. ‘I want to achieve big changes here,’ he beamed. He was dressed in a Superway shirt and slip-on carpet shoes. ‘I want to make this store a beacon. A true retail experience.’

No-one reacted. The shelf-stackers glowered. The only sound was the slow clack-clack of gum.

‘We start today,’ he announced the next morning. I was getting ready on the deli counter, pulling on my sanitised gloves. ‘The deli counter is closed,’ he said. ‘No customer access from aisles ten to 14. I want to move some things around. Things are going to look a bit different.’ We exchanged puzzled glances. A doss, we imagined. But Mr Fung had other ideas.

The first thing he wanted us to do was drag the deli counter out so it protruded at right angles from the wall. It required ten members of staff to shift. In order to make space for this we had to reposition several aisles, which meant first removing all the products from the shelves. ‘Stack them up against the back wall,’ said Mr Fung. ‘Customers will still want to buy these things, so let’s try to create an orderly new zone.’ But that wasn’t easy. At nine, the doors opened, and customers began filtering in. They were quite confused. The supermarket looked like a construction site. ‘We apologise for inconvenience,’ announced Mr Fung with a microphone at intervals throughout the morning, ‘several aisles are temporarily closed as part of Superway’s reorganisation. Feel free to look for the products you desire along the wall at the back of the store. Things will be back to normal soon, enjoy your Superway experience.’

‘I want to get some biscuits,’ a customer told me, gesturing bad-temperedly down the 12th aisle. Access was blocked by a barricade of trolleys we’d erected where the shelving began, and members of staff were ferrying products to the growing heap by the wall.

‘This aisle’s closed today,’ I said. ‘Everything’s getting moved around.’

‘Why is this happening?’ asked another. ‘It’s impossible to find anything.’

‘Sorry, you’ll have to look in that pile,’ was all I could suggest.

‘Good work,’ said Mr Fung at the end of the day. The automatic doors were closed and the checkout assistants were cashing up. ‘We’ve made a good start. You’ve all done well. Things look a lot less linear now.’ He nodded approvingly down the shop floor, where aisles ten to 14 had once stood. The symmetry of the aisles had gone. Aisles ten and 11 were positioned at right angles, and 12 and 13 protruded diagonally, creating a confusion of planes. ‘That’s just the beginning,’ he declared.

Over the course of the following week, under Mr Fung’s direction, we systematically disordered the remaining aisles, starting with aisles five to nine, then aisles one to four, and finally the various counters. By Saturday, the shop floor was unrecognisable. Some of the aisles led to dead ends, and the positioning of others created small rooms to which access could only be gained through a narrow gap between shelves. Us staffers wandered these new lanes, trying to make sense of what we’d done. The experience was disorientating. It was like a badly designed labyrinth.

‘Excellent,’ said Mr Fung. We were gathered around him in a semi-circle, eating the chocolate ice-cream bars he’d handed out in appreciation of our efforts. ‘I think this creates a much more interesting space. This will be a retail

experience. Next week’s job is getting products back on shelves. We can’t expect our customers to root round in that pile forever.’ He grinned, and gave an exaggerated wink. None of us knew what to make of it.

On Monday morning, Mr Fung explained his plans for reorganising the products. ‘We’ll mix things up a bit,’ he said. He was wearing a shiny purple suit and casually tossing a tangerine from one hand to the other. ‘Customers develop patterns, you know. They buy the same things time and time again. They adopt certain habits. That’s not good for retail diversity. That’s not good for business.’ He wandered over to the mountain of products heaped chaotically at the back, and gazed at it intently. ‘Stack these according to taste,’ he said. ‘Salty things starting from the right hand side, spicy in the middle, sweet at the far left. There will obviously be some crossover zones, sweet and spicy being the most obvious example. Any questions about taste classification, ask me. Right, let’s get started.’

No-one moved, or said a word. We were dumbfounded. Mr Fung regarded this inertia, then drew back the sleeve of his jacket and consulted his watch.

‘It’s four minutes past seven,’ he said. ‘We’re open for business in two hours time. By eight fifty-five, I want to see this Superway divided into those three declared zones: salty, spicy and sweet. It’s a big job, what are you waiting for? Let’s

go!’ And with this, he flung the tangerine directly at Tony, the surly 18 year-old who usually worked at the fish counter. The fruit plumped into Tony’s chest, and splatted softly on the floor. Tony stared in disbelief. ‘Let’s

go!’ yelled Mr Fung again. There was no disagreeing with that.

The task was enormous, and ridiculous. There was no way we’d have finished it by nine. But it turned out that didn’t really matter, because barely half an hour later, Mr Fung made another announcement.

‘Okay, change of plan,’ he cried, bounding down the aisle. ‘I’ve been rethinking our marketing strategy. This division of products won’t work. It’s too simplistic. Customers won’t like it. They’ll think we’re patronising them. I’ve also brainstormed a number of products that may present some difficulties – fall through the net, as it were.’ He consulted a clipboard. ‘Yeast, for example. So, what we’ll do instead is this: stack everything

alphabetically.’

‘Do what?’ someone asked in disbelief.

‘Start with the A products at the far left – almonds, anchovies, aniseed, aspirin – and work our way through the Bs and the Cs all the way down to Z. If we have any products beginning with Z. It’s possible we don’t. This, I believe, is the most logical way to order the store. It will also be educational for junior customers. Any questions?’

Wasim, a balding shelf-stacker with a large Adam’s apple and watery eyes, spoke up doubtfully. ‘Are fruit and veg included in this? Do we put apples between… uh, aniseed and… uh, aspirin?’

‘Fruit and veg are exempt for now. I’ve other plans for them.’

‘How about refrigerated goods?’ asked a grave-faced Slovakian girl called Leena.

‘For now, refrigerated goods will fall under category F, for Frozen. Or perhaps under I for Icy, I’m not sure. Please consult me further on this when you get towards the end of the Es.’

So we set to work. There were cynics amongst us. ‘No fucking way is this going to work,’ said Ranjeet, my fellow deli-counter worker, in his habitually put-upon tone. ‘I’ve worked in enough supermarkets, and I’ve never seen anything fucking like this. This is not how supermarkets go.’

‘This is not how

most supermarkets go,’ said Mr Fung. He was standing behind us, holding an economy tin of butter beans. His soft-soled shoes meant you couldn’t hear him coming. Ranjeet and I both stepped back, eyeing the tin nervously. ‘This, however, is not most supermarkets. This is a retail

experience. In time, you will learn this,’ He gave Ranjeet’s arm an encouraging slap. Ranjeet looked even more unhappy.

When the clock went nine the doors were still closed, and I could see the faces of customers peering through the tinted glass. ‘We’re only on D,’ Wasim explained when Mr Fung came back to take stock. ‘We have to keep rearranging it all. We find another thing that starts with B, and we have to slide the other products down.’

‘We can’t get this done. Not with customers in. I mean, no fucking way,’ said Ranjeet.

‘Okay, I’m taking a managerial decision,’ announced Mr Fung. ‘The store will not open today. We are closed for re-categorisation. Things will be back to normal soon, we apologise for inconvenience caused, but this is an important part of Superway’s reorganisation.’ He pointed at me. ‘Go out and tell them this. Be polite but firm. Don’t let them bully you. And then write a sign and stick it on the door.’

‘Sorry, we’re not open today,’ I said to the people waiting outside. I only opened the door halfway in case one of them tried to squeeze through. ‘We’re closed for re-categorisation. Things will be back to normal soon and we apologise for any inconvenience. It’s an important part of Superway’s reorganisation.’

‘What’s going on in there?’ asked an old woman I recognised. ‘Why have you done that with the aisles?’

‘This is ridiculous,’ said someone else. I gave them an apologetic smile and slipped back inside.

‘You can’t close a store down like this, man,’ hissed Ranjeet disbelievingly, as we sifted through the product mountain for things starting with E. ‘That’s not how supermarkets work. It’s just not something you can do

.’

But, as we were starting to discover, Mr Fung could.

When we opened up again two days later, the Alphabetisation was complete. Walking the aisles, already disordered, or ‘de-linearised’ as Mr Fung termed it, was a strange and bewildering experience. It went against every retail convention we’d ever known.

The various sections were demarked by capital letters painted on cardboard in Superway’s trademark lime green. Fish-counter Tony had painted the letters, and his calligraphy skills weren’t good. The letters were drippy and badly composed. ‘We’ll get proper signs made up,’ said Mr Fung when Leena complained they looked unprofessional. ‘This is just a stop-gap, you know. Nothing is permanent. The important thing is to see what works. We learn by a process of trial and error. This store is a living experiment.’

But dissent was growing in certain quarters. There were those amongst the staff who objected to living experiments, or experiments of any kind at all. The staff were an unexperimental bunch, an assortment of cynics, school dropouts, slackers and hard-working recent immigrants; for some this was essential employment for sending money home to their families, while others had nothing to spend their wages on but weed. If anything united us, it was the unquestioned assumption that employment in a Superway store could never turn out to be anything but a monotonous repetition of tasks. In other words steady, non-challenging work, with no sudden shocks or surprises. And most of us quite liked it that way. There was a certain comfort in boredom. Living experiments weren’t in the job description.

The first to jump ship were Gabby and Nicole, two best friends who worked on the tills, and whose names I could never get the right way round. They were attractive in a dull kind of way, but clearly had what Mr Fung later termed a ‘low imagination threshold’. I assume the changes simply freaked them out. They didn’t turn up for work one morning, and soon afterwards they were joined by Mike, who worked in the unloading bay, and a chubby stoner called Doff who suffered from a bad skin condition. From that point on, the Superway experienced a slow haemorrhaging of labour. Mr Fung didn’t appear to mind, and never made any attempt to recruit extra staff. ‘This is what we call a streamlining process,’ he said, in one of his morning meetings, when Wasim pointed out the fact we no longer had any security guards. ‘This store is downsizing. Re-evaluating. And anyway, we don’t really need security at present.’

This was true. The doors had been closed for a week while other changes were implemented. Mr Fung had ordered carpets to be laid down the length of each aisle, to give the shop-floor a ‘more tactile feel,’ and drapes to be hung from the ceiling to make the place ‘cosy.’ Following his emotive tirade against the strip-lights which made the store ‘like one of those places you identify corpses,’ we had also spent several days fitting incandescent bulbs and rigging up paper shades to diffuse their glare. It did not matter to Mr Fung that none of us were qualified to rewire electric lights. He provided overalls, directing the proceedings from a swivel chair he had wheeled from his office to the middle of the store. Occasionally he leapt up from this throne to patrol the evolving aisles, stopping now and then to scribble notes in his pad. His ideas changed rapidly and without warning, and it wasn’t unusual for a team to spend an entire morning on one task, only to dismantle it after lunch. But Mr Fung was exuberant. His enthusiasm was boundless. And the more his detractors fell away, the more his strange zeal came to affect those of us who remained.

‘He’s out of his tree. He’s wrong in the head,’ said Ranjeet one evening after work, after he had spent the whole day painting the trolleys green to make them look ‘less like cages.’ ‘I’m telling you, man, it’s too fucking weird. If it goes on like this much longer, I’m getting out.’ But I could tell that – like most who remained, who weathered the desertions in our ranks and stayed to work at the Superway through its various incarnations – he was secretly fascinated.

Already, in those early days, I think a few of us were starting to see Mr Fung for what he really was. A retail visionary.

He took me aside a few mornings later, the moment I got to work. I don’t know why he singled me out, but he appeared to have it planned. He was wearing a different suit that day, a slightly louder shade of purple, along with a truly hideous veined purple tie.

‘What’s your usual position in this store?’ he asked. ‘I mean, before.’

‘I normally work at the deli counter.’

‘

Deli’, he muttered, as if he hadn’t thought of that. He looked confused and worried for a second. But then his face brightened again. He had taken me by the elbow, and was guiding me towards the front of the store, where the sliding doors were. ‘Well you won’t be at the deli any more. In fact, we may not even have a deli. I want you to be in charge of organising the garden.’

‘The garden?’ I asked, confused.

‘Tell me, when a customer enters a supermarket, any supermarket, in any country, what is the first thing he sees?’

‘Newspapers. Magazines. Fruit and veg.’

‘Correct. And why does he see fruit and veg?’

‘Because it’s green and fresh. It makes the place feel healthy.’

‘Exactly, yes. Green and fresh. And this Superway store will adhere to that principle. There are some conventions that can’t be changed. However, they can be

improved, re-imagined. Where does fruit and veg come from?’

‘Where does it come from? Lots of places.’

‘I’m speaking fundamentally,’ he said, snapping his fingers impatiently. ‘Does it come from a factory? Out of a tin?’

‘Uh, from trees, bushes, the ground…’

‘Exactly right,’ beamed Mr Fung. We had reached the fruit and veg shelves now – they were empty, having been bare for a week, with only a few root vegetables and wilted stalks to show what they had been before – where he gestured expansively. ‘You think our customers want to see these green, fresh things on those plastic shelves, in those temperature-controlled compartments, under those glaring lights?’

I shook my head. He was staring at me. I couldn’t imagine what he wanted. He unfolded several sheets of paper covered in diagrams.

‘These,’ he said proudly, holding them before me, ‘are my plans for Fruit Eden.’

I stared at the paper. It was incomprehensible.

‘Fruit Eden?’ I asked uncertainly.

‘That is how it will be known. The concept is based, loosely, on the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.’

I studied the papers in more detail. The plans looked entirely improbable. From what I could tell from the ‘artist’s impression’, oranges, apples, bananas and melons were clustered together in some sort of steaming tropical forest. There was a meadow of salad leaves, a kind of Japanese rock garden bristling with herbs, and what appeared to be a waterfall cascading down one of the walls.

‘This is only provisional,’ Mr Fung said, as if sensing my doubt. ‘The exact details of the plans may change in the execution.’

‘And I’m in charge of this?’ I asked.

‘I’m giving you full control.’

‘And how… how do I make this stuff?’

‘It’s up to you to implement the vision in the way you see fit. I’ve been watching you work. I trust your abilities. You must use all materials at your disposal, and hand-pick a small team of assistants from amongst the staff. It is my intention that Fruit Eden will be one of this store’s greatest assets, a true retail

experience. You have two weeks to complete the project, after which time the doors will reopen to the public. Any questions?’

Dumbly, I just shook my head. I didn’t know what else to do.

For my team I selected Leena, because I liked her seriousness, Ranjeet, to get him off painting trolleys, and a Kurdish guy I barely knew called Kaseem, because I liked his face. I also picked surly Tony, who, against all expectations, had stuck it out against Mr Fung’s occasional tangerine assaults, and appeared surprisingly unfazed by the store’s gradual slide into madness. Tony seemed a good solid type, and proved to be useful when it came to hammer-work and heavy lifting. We had our first meeting later that day, smoked a pack of cigarettes between us, cordoned off the proposed work area, and dragged the old shelves into storage.

That afternoon, using the expense account Mr Fung had given us, I ordered 20 bags of concrete, five rolls of Astroturf, ten tarpaulins, 30 metres of hose, 12 bags of soil and 12 bags of fertiliser. The next morning, Ranjeet and I drove to the nearby garden centre in a home delivery van to load up with ivy, ferns, assorted creepers and vines, a dozen rubber plants, ten banana trees, and as many potted herbs as we could stuff into the racks. We spent whatever money was left on orchids and Venus fly-traps. The bill ran into the thousands.

Fruit Eden evolved haphazardly. We had no idea what we were doing. Tony and Kaseem had both had previous jobs on building sites, so all the concrete and structural work was their responsibility. By the end of the fourth day, they had constructed two large ponds and a monstrous concrete feature, which was supposed to look like rocks for the cascading waterfall. Ranjeet and I tried to get it working, running hosepipes up the wall, but the water came out in a pathetic trickle so we decided to cut shelves into it and turn it into ‘Citrus Rock’, which would display lemons, limes and oranges and be festooned with bougainvillea. Instead of a waterfall, we had to settle for a couple of dribbling fountains. The concrete ponds we filled with water lilies, on which could be balanced little plastic signs informing customers of important price reductions.

The five of us came to enjoy a minor celebrity status in the store. Select groups of the other employees were engaged on several notable side-projects, but most were still slugging away at the seemingly endless re-categorisation of products. Mr Fung had since had doubts about the Alphabetisation system, and for three days had become obsessed with what he called ‘Full Product Spectrum,’ or, sometimes, ‘Consumer Rainbow.’ His new idea was to display everything according to colour. The left-hand side of the store would be red, and then orangey-red products would give way to an orange section, which would blend seamlessly into yellows, following the colour spectrum through greens, blues and purples into blacks, against the right-hand wall.

Or at least, this was the idea. It didn’t prove popular. The prospect of taking all the products off the shelves again and putting them back in yet another order caused a minor rebellion amongst the staff. There was a rash of further walk-outs. At first people refused to get involved, and when they did, they did the job badly, so it was less a Consumer Rainbow than a mish-mash of different colour patches, the result of which sent Mr Fung into a rage. It was the first time, I think, that anyone had seen him angry. He stormed off into the loading bay, muttering furiously to himself, and remained in there for several minutes. When he came back, to the amazement of everyone, he publically recanted. ‘I’ve brainstormed the Full Colour Spectrum, and concluded the concept will not be adopted by this Superway store. After careful consideration, I’ve decided the rainbow effect may well prove distressing to some customers. There are certain psychological effects that cannot fully be predicted – people getting angry in the reds, or nauseous in the yellows. Aisles of unbroken grey might create depression. In light of these potential risks, the process of re-Alphabetisation will begin forthwith.’

Critics of Mr Fung used this speech as evidence that he lacked overall vision, that he was growing confused and indecisive. His supporters said it showed that he was listening to his workers’ concerns, that he was not the maverick egotist his detractors made him out to be. Further rifts began to grow among what remained of the staff, from which those of us employed on Fruit Eden were happily exempt. We were working on a higher project, something with grandeur and scale. We didn’t need to involve ourselves in these petty intrigues. Our exclusivity didn’t make us popular, however: there were rumours we were being paid more, that we enjoyed special privileges.

By the end of two weeks, our Fruit Eden looked like a half-built theme park. We asked for more time. We were given four days. We worked flat-out for the whole period, staying after work until ten or ten-thirty to finish laying Astroturf, spreading fertiliser over the beds, pressing flowers into the moist soil. Tony really took to this. He had never planted anything before. Gradually, unbelievably, the project came together. Mr Fung sat in his swivel chair, checking his charts and eyeing our work, until we finally put down our tools and left at the end of the night.

In all the time I worked for him, I never saw Mr Fung leave the store. There were rumours that he slept in his office on a bed made of packing crates, but these stories were never confirmed, because no-one had ever been in there.

On the morning of the grand opening, we stocked the shelves with produce. In several areas we had borrowed from Mr Fung’s Full Product Spectrum concept, and Leena had created gorgeous displays of fresh fruit. Citrus Rock was spectacular, rising from lemon-yellow at the bottom, through diffusive grapefruit tones, into topmost shades of deep blood orange-red. It looked like a thermometer about to burst. Other fruit was clustered together into something that loosely resembled the original tropical jungle plans, bananas, pineapples and melons displayed in a glistening forest of green leaves. The herb garden looked pretty shabby, but I was confident it would improve with nurturing. Leena’s main addition to the project was the creation of the ‘Lettuce Meadow,’ an expanse of salad leaves arranged across a wide sloping area, access to which could be gained by a narrow wooden bridge.

The last things to go in were several industrial humidifiers, which had raised the cost of the project by another few thousand pounds. They covered the area in a fine mist. It was like being in a tropical greenhouse. The disadvantage of the humidifiers was that anyone entering Fruit Eden got soaked to the skin in seconds, but we planned to supply waterproof ponchos for customers to use free of charge.

Mr Fung announced the grand opening over the loudspeakers. Today, he said, was the culmination not only of the Fruit Eden project, but the ‘re-imagining’ process that had taken place across the whole store, from the Alphabetisation of the shelves to Fish World and the Frozen North, right through to the bloody spectacle of Meat Zone. He congratulated all remaining staff, those of us who had stuck it out, who had not shied away from experimentation or faltered at new ideas. Tomorrow, he declared, the doors would reopen, and ‘a new supermarket paradigm’ would at last be unleashed on the world.

Mr Fung popped a bottle of Cava, and raised his plastic glass to Fruit Eden. The humidifiers steamed up the glasses on his face, mist condensed on his forehead. We watched him, anxiously, for an opinion. He appeared absolutely delighted, almost childishly happy.

After a short opening ceremony, in which Mr Fung had donned a poncho, crossed the bridge over Lettuce Meadow, plucked an apple from the Tree of Knowledge – this, surprisingly, was Tony’s inspiration, an ungainly concrete construction enwrapped by a serpent made of painted hosepipes – and taken a ceremonial bite, the staff were encouraged to spend time wandering around the store, in order to familiarise ourselves with new developments. I stuck with my team, each of us swigging from a mini bottle of white wine, which Mr Fung had distributed from a loaded trolley. We saw the Frozen North, the icy bunker that comprised the new frozen foods department, and had a look at Fish World, which was unpleasant. We sat down on the sofas, armchairs and chaises longues that had appeared halfway along some of the aisles, to provide ‘calm spots’ whenever customers grew fatigued. We explored the bewildering labyrinth of shelves, which had changed shape four or five times since I had last been involved, and made even more disorientating by the erection of screens and the hanging of curtains, all part of Mr Fung’s self-declared ‘war on linearity.’

‘What about security?’ Wasim had asked several weeks before.

‘Security?’ said Mr Fung, as if he scorned the word.

‘I mean, CCTV cameras and stuff. How will they see the shoplifters now? There are blind spots everywhere, all over the store.’ Wasim, despite his permanent expression of fear intermingled with doubt, was one of those loyal employees who had stuck it out.

In response, Mr Fung had told a surprising story.

‘After the revolutions in France, the government redesigned Paris. All the new roads were built in straight lines, a bit like conventional supermarkets. Do you know why? To give cannons a clear line of fire. That’s the same principle behind security cameras. To give them a clear line of fire, to eliminate blind spots.’

The assembled staff were puzzled and impressed. At times like these, I had the sense that Mr Fung was hinting at something that went beyond new retail experiences and supermarket paradigms. As if he was revealing something hidden.

‘Do we want to create that sort of store?’ Mr Fung went on. ‘A supermarket founded on the fear of the very people it serves?’

‘But what about the shoplifters?’ asked Wasim, standing with his mouth slightly open.

To this, Mr Fung had said nothing.

We finished our mini bottles of wine, and pushed Tony around in one of the trolleys that Ranjeet had painted green. We practised locating products under the Alphabetisation system, in preparation for the opening next day. It wasn’t as straightforward as it sounded. At first it was hard to guess, for example, whether a bar of milk chocolate would appear under C for chocolate, M for milk chocolate, or even B for bar. People had told Mr Fung of these concerns. He’d called them ‘teething problems.’

My team wandered off. It was dark outside. All the lights were blazing in the store. I kissed Leena when we were alone, in one of the rooms created by the positioning of aisles. It was a hasty, clumsy thing, and both of us laughed afterwards. We were surrounded by L-products: lager, lard, lasagne sheets, lemonade, lipstick, Listerine, lollipops. I tried to sit her in her own shelf space, between leashes and leggings.

‘This is one of Mr Fung’s blind spots,’ I said, putting my lips against her neck. I don’t know if she got the reference. I thought it would seem embarrassing later, but it never did.

We resumed trading the next morning. The doors to reality opened.

The reopening hadn’t been advertised, so it took a long time before any customers actually came. Mr Fung greeted them at the door. He was wearing his purple suit, with a pink bougainvillea flower in the lapel. He shook their hands, welcomed them to the store, and personally handed them a shopping basket or matched them up with a trolley. ‘Take your time,’ he said. ‘Make yourself at home.’

The customers entered cautiously, with a look of trepidation. The first thing they encountered was Fruit Eden. The humidifiers were on full blast, and before long the condensation built up and dripped from the ceiling like rain, which we hadn’t anticipated. We had to hand out umbrellas to go with the waterproof ponchos. Despite these protections, few of the customers actually ventured over the bridge that spanned Lettuce Meadow. They were not adventurous. Some took lemons from Citrus Rock, but to get to the ruby grapefruit and blood oranges they had to climb 12 feet up a ladder, and none attempted that. They dithered at the edges and stared. They wiped perspiration from their foreheads. ‘It looks nice, I guess,’ one man said. But nobody else said anything.

From there, they entered into the aisles, following the alphabet. Tony’s sloppy letter signs had been replaced with smarter ones, printed in the Superway green on plastic notices, but they still seemed to find the system confusing. They constantly had to ask where things were. They seemed upset by the lack of straight lines, and half the little rooms remained unexplored. They came upon darkly watchful employees positioned at every junction, staring at them to see how they reacted.

The wheels of their trolleys caught on the carpets. Some of them got hopelessly lost. They kept knocking things off the shelves. There was growing irritation.

At the end of the day, when the last of them had found their way back and been ushered out, the sales on the tills were disappointing. We’d received 16 complaints, with one man threatening to sue over slipping on the wet floor at Fruit Eden. Comments included ‘disorientating’, ‘nightmarish and Kafkaesque’, ‘an impossible environment to shop in’, and ‘a revolting joke’. This last was a comment about Meat Zone, which seemed to have caused quite a stir.

‘Teething problems,’ said Mr Fung, in his subsequent debriefing. We were gathered around the tills, passing round the packet of rich tea biscuits he had handed out. ‘Of course it takes time for new ideas to filter through to the public. They have never seen anything like this before. They are overwhelmed. The more revolutionary the concept, the harder it is to comprehend.’ He appeared defiant and upbeat, hopping round energetically and beaming at us all. He assured us that sales would pick up, that customers would come flocking before long.

At the end of the first week, as customer footfall increased slightly, Mr Fung was still confident enough to initiate a new rota system he called ‘Staff Switcheroo’. The idea, he explained, was to counter monotony creeping in as we all settled down to our regular jobs, now that the excitement of the reorganisation was over. He didn’t want us to grow despondent. He didn’t want a workforce of automatons, he said. Throughout the day, at intervals of between 15 minutes and two hours, an announcement would be broadcast overhead: ‘All staff switch, all staff switch, with immediate effect. Thank you.’ Upon hearing this, all employees would immediately move to a new position: check-out staff would turn into shelf stackers, shelf stackers would man Fish World, Fish World servers would collect trolleys, trolley attendants would rush to the loading bay. We all carried laminated sheets that told us the order of duties.

We did a trial run before opening, and everything went pretty smoothly. But when the customers were in, the changeovers quickly became chaotic. People would complain about shop attendants charging off in the middle of helping them track down some product beginning with J, sometimes leaving halfway through a sentence. An elderly woman was almost knocked over in the rush to get through the aisles. ‘Things will settle down,’ said Mr Fung. ‘After a few weeks, Switcheroo will become so effortless and natural you can do it blindfolded.’ He frowned, thinking for a moment, and it wouldn’t have surprised me if he’d whipped out blindfolds there and then. But he turned away.

At the end of that month, Mr Fung’s smile no longer came so easy. His feet had lost their bounce. Things were going badly wrong, despite the reassurances and pep talks he gave us in the morning meetings, which even some of his loyal supporters had started to call propaganda. Sales, which had initially picked up following that first ‘teething’ week were steadily falling. We took less every trading day. Our regular customers had deserted us. New customers came once, sometimes even twice, but not again. The only regulars we managed to attract were a collection of mad old tramps, who came to put their feet up on the

chaises longues or wander the aisles for the afternoon, smiling happily to themselves, picking things up and putting them down again.

Either it’s a tribute to Mr Fung’s inclusiveness, his generous soul, that he didn’t have those tramps thrown out, or a mark of his desperation.

Employees continued to fall by the wayside. Even those who Mr Fung had inspired, those who had initially glimpsed his bright new dawn. We were down to a skeleton staff. Me, Ranjeet, Tony, Wasim, Leena and a score of irregulars. Kaseem had quietly vanished a week ago. And then Tony quit as well. He said he had to study for exams, but I lost all respect for him.

‘You’re not going to quit, are you?’ I asked Ranjeet one day, after he’d been bitching about the long hours and the fact we were still on the minimum wage.

‘Quit?’ he said. ‘I don’t quit, man. I’m not quitting smoking, and I’m not quitting Fung’s.’

This, I think, was the first time that anyone had called it this. Out loud, at any rate. Perhaps we’d all begun to give it this name in our minds long ago. He was right: it wasn’t Superway now. It was Fung’s. There could be no other name.

I still kissed Leena from time to time. On the bridge over Lettuce Meadow, or in the chaos of the Switcheroo. She’d write a single letter on the back of a receipt and we’d meet in the Gs or the Ks or the Ns, rush through the motions of a brief, fumbled tryst, and then hurry back to our duties.

But Fung’s plunged deeper into problems by the day. It was like being on a sinking ship. We’d practically gutted and rebuilt the place in a couple of inspired weeks, and now our deficiencies in design, planning, construction, engineering, electronics, hydraulics and everything else were becoming alarmingly apparent. Fish World stank. Almost no-one could enter. The Frozen North was in crisis. There was some problem with temperature control, and ice now covered the walls and floor, with icicles starting to grow down from the ceiling. Chisels had to be provided to hack away rock-hard sausages that had become imbedded in the walls, like prehistoric hunters. Meat Zone was another liability. Children had run howling from the sight. There was blood seeping through one of the walls, and no-one could work out where it was coming from.

By the end of a fortnight, it was clear that even Fruit Eden was failing. Digging out wilted produce and getting fresh stuff onto shelves proved to be a laborious business, and with the staff shortage and the constant Switcheroos the job wasn’t done properly. The area was nearly impossible to clean. Decomposing matter built up in the cracks. The bright hues of Citrus Rock slowly faded from yellow to brown, and Lettuce Meadow turned into a sodden swamp. Dark shadows of damp appeared on the walls, and the humidifiers had to be decommissioned. There were fruit flies circling, despite the Venus fly-traps.

The worst thing was the change in Mr Fung. We watched as his energy drained away, with occasional resurgences of zeal, the fervour repossessing him, sometimes for hours at a time, and then dissipating again. The vigorous speeches became less frequent. He no longer threw things at people. He spent more time sitting in his swivel chair, gazing at the slow train-wreck of his store, turning circles with his feet. Just going round and round.

We all waited for the next big idea, the next doomed, inspirational scheme to get things moving, to turn things around, to check the steady rot. We would have gone along with it, too, we who stayed with him to the end. We would have followed any fresh, crazed vision, even if – perhaps especially if – we knew it could only fail. It would have been worth it, just to see the old eagerness filling him again, his face lighting up like a fridge when it’s thrown open.

But after a point, the big ideas stopped coming.

It happened one day shortly after closing, when the tills were being emptied of their miserable takings, the lights switched off in the grottoes of Fruit Eden. It was Wasim who opened the doors, apprehending that the two men outside, the two men with the suits and the briefcase, were not customers arriving late but a portent of something else. Something composed and official. They were both tall, clean and middle-aged, with the kinds of haircuts tall, clean, middle-aged people have. They looked like the sort of people who know the names of motorways and listen to traffic reports. They asked to see the manager. We led them towards the office. I could see their eyes flicking around as we navigated them through the aisles, but the expressions on their faces never altered. I was the one who opened the door, and I tried to see if there was a bed made of packing crates in there, but all I could see was a neat desk, with files, folders and a calculator arranged on it.

Mr Fung received the men with a calm, acceptant smile. He shook their hands and stepped aside to let them through, then closed the door. There was something embarrassing about the glimpse I had of him, just before the office door closed. He suddenly looked ridiculous, smiling away in an ugly purple suit that was slightly too large, a wilted bougainvillea in the lapel. I felt a rush of shame.

‘That’s it. He’s in the shit now,’ said Ranjeet, half an hour later. The office door was still closed. None of us had left.

‘Why? Why do you say that?’ demanded Leena. She was sitting on my knee. It wasn’t very comfortable; she was a bony girl.

‘I reckon they’re the guys who own the franchise. They’re the guys from Superway.’ He was sitting at a cash register and smoking, knocking the ash into one of the empty drawers.

The two men left after an hour and a half. When their car had gone, the carpark was empty. We waited for another 15 minutes to see if Mr Fung would come out, but he stayed in his office. It didn’t seem right to disturb him.

The next morning, he made a short speech. This Superway store was closing, he said. He was stepping down as manager. It was not economically viable. He hoped it would reopen under different management, so we could keep our jobs. He was sorry things hadn’t worked out. And he wished he could give us some severance pay, to last until things were back to normal, but there was no money available.

‘That’s it?’ said Wasim. His Adam’s apple went up and down. I thought he was about to cry.

‘Yes. That’s it,’ said Mr Fung.

‘What about everything we’ve done?’ demanded Ranjeet furiously.

‘There’s nothing more to do,’ said Mr Fung. ‘This store is prefect, in every way.’ He smiled sadly. ‘I’m very, very proud.’

The doors didn’t open that day. Or ever again, for that matter. I don’t know if Superway planned to reopen under new management, to wipe away everything we’d done and return things to the way they were, but with the economic situation and the general pattern of closures nationwide, I suppose the odds were pretty much against it. I’m glad, of course, it has been this way. I’m glad that nothing came after. Given that the Superway brand itself went bust about a year later, laying off thousands of staff across the country, it might seem, to a fantasist, almost a vindication. But history has no jurisdiction to vindicate men like Mr Fung. He needs no-one’s approval. He’s beyond it.

It was Ranjeet who suggested it, though he said it as a joke. It was me who took the idea up and made us follow it through. We got to work that afternoon, the last afternoon we spent at Fung’s, cutting the letters from balsawood with a hacksaw in the car-park. We painted them lime green with the paint that Tony had used for his letter signs. Then we got a ladder and climbed onto the flat, gravelled roof.

It was hard to get the old sign off, but we managed it with a mallet and a crowbar. There was no risk in cutting the wires, because the electricity had been disconnected earlier that day. Under our feet, the fruit flies were swarming over the rot of Fruit Eden; the Frozen North was melting now, loosening its grip on the sausages. We sent the Superway sign crashing down in three broken pieces to the concrete below. Leena let out a scream and jumped around. There was no-one else to applaud or cheer. No-one to witness the final switcheroo.

We banged the letters into place with ten-inch nails, right into the wall. F, FU, FUN, FUNG, FUNG’S. There was no way to light them up, of course, but they stood out brightly, lime green on grey-black. Then we went to find Mr Fung.

He stood there for a long time, looking at the sign. There was no expression on his face at all. He wiped his glasses, put them back on, and nodded his approval. Leena laughed. So did Ranjeet. Myself and Mr Fung remained silent.

Finally we followed him inside, back into the unilluminated store.

‘Take what you want,’ was the last thing he said. ‘Anything. It’s all yours.’

But we didn’t really feel like taking much, in the end.

I never saw Wasim again. I imagine he’s doing okay. I hung out with Ranjeet for a while, but we started to annoy each other, and after I went to university we lost all contact. All we talked about was Fung’s, and when there wasn’t anything else about Fung’s left to talk about, we didn’t have much to say. I saw Leena on and off that summer. She got a job in a family greengrocer’s. I have no idea what became of her. She was the first girl who let me touch her breasts.

And where did Mr Fung go then? What’s he doing now? I’ve asked around. No-one seems to know. He wasn’t the kind of man you keep in touch with.

Was he married? Did he have a family? Where did he even come from? No-one seems to know that either. Sometimes I wish I’d talked to him, asked him more questions.

The story of Mr Fung’s Superway has since become a textbook case of mismanagement at a senior level, of doomed market strategy. It is studied in business studies seminars, held up as an extreme example of how a franchise can go badly wrong if chains of command are not adhered to and oversight not maintained. CEOs talk about ‘doing a Fung.’ Consumer watchdogs use it to explain the collapse of accountability structures. Health and safety panels do slideshows about it, pointing out the lack of fire extinguishers and flagrant disregard for safety signs.

Those little men, those little women. I can only pity them. I know how it really was. I lived through the glory days.

*

I drove past Fung’s a few days ago. Of course, it isn’t Fung’s now. I drove past Fung’s, and then left it behind. I could have stopped, but what would have been the point? You can stop, but you can’t go back.

I’m not sure what was more bizarre: the burning bus itself of the pictures of the burning bus – my burning bus – on news sites, in the paper, on TV. The police were not treating the incident as suspicious, which struck me as odd. Not that I suspected terrorism – not at all. But still, a burning bus, or rather an exploding bus, struck me as incredibly suspicious. A robbery of sorts. That was our local bus, I felt like shouting. And now it’s gone, without so much as a police investigation.

I’m not sure what was more bizarre: the burning bus itself of the pictures of the burning bus – my burning bus – on news sites, in the paper, on TV. The police were not treating the incident as suspicious, which struck me as odd. Not that I suspected terrorism – not at all. But still, a burning bus, or rather an exploding bus, struck me as incredibly suspicious. A robbery of sorts. That was our local bus, I felt like shouting. And now it’s gone, without so much as a police investigation.

I’ve since moved out of that house, but I still live in the same area, and I still ride the 343 every now and then. Recently, after visiting a friend near London Bridge I decided to ride it home – something that I hadn’t done in some time. It was a rainy afternoon. Blustery. The bus was nearly full. The windows had fogged up. It would be a long journey, but I didn’t mind. The 343 is one of those circuitous buses. It traverses few main thoroughfares, choosing to snake down the suburban roads, the backstreets, all the way from City Hall to New Cross Gate. This can be explained by the fact that the 343 wasn’t always the 343. Before the route was sold to Abellio – a Dutch transport company, one of the handful of private corporations in charge of London’s various bus routes – it was known as the P3, one of those single-deckers meant to shuttle pensioners and schoolchildren from door, to shop, to door. When Abellio bought the line, they expanded the service. Now it’s one of the least efficient bus routes in all of London,among the ten worst performing in the whole city.

I’ve since moved out of that house, but I still live in the same area, and I still ride the 343 every now and then. Recently, after visiting a friend near London Bridge I decided to ride it home – something that I hadn’t done in some time. It was a rainy afternoon. Blustery. The bus was nearly full. The windows had fogged up. It would be a long journey, but I didn’t mind. The 343 is one of those circuitous buses. It traverses few main thoroughfares, choosing to snake down the suburban roads, the backstreets, all the way from City Hall to New Cross Gate. This can be explained by the fact that the 343 wasn’t always the 343. Before the route was sold to Abellio – a Dutch transport company, one of the handful of private corporations in charge of London’s various bus routes – it was known as the P3, one of those single-deckers meant to shuttle pensioners and schoolchildren from door, to shop, to door. When Abellio bought the line, they expanded the service. Now it’s one of the least efficient bus routes in all of London,among the ten worst performing in the whole city.

The bus halted in traffic at Elephant and Castle. I rubbed the fog off the front window to see the large construction site just beyond the old shopping center. This used to be home to the Heygate Estate, which was demolished last year. A few cranes swayed in the wind. A man sipped a cappuccino outside one of the refurbished shipping containers at the new Boxpark. I had no right to get romantic about the Heygate – it was a hellish, rusk-hulk of a ruin. But this too felt bleak. Just beside the Boxpark was a large digital picture of the world to come: the new development was to be called Elephant Park, and flats were officially for sale. Old London burnt up, purified by fire, making way for the boxy corporate design of condos and flats, soon to be home to white-collar workers, low-level execs, those trying to get a rung on the property ladder. A bastion of healthy living: a gym, rooftop gardens, a children’s play area – residents’ access only.

The bus halted in traffic at Elephant and Castle. I rubbed the fog off the front window to see the large construction site just beyond the old shopping center. This used to be home to the Heygate Estate, which was demolished last year. A few cranes swayed in the wind. A man sipped a cappuccino outside one of the refurbished shipping containers at the new Boxpark. I had no right to get romantic about the Heygate – it was a hellish, rusk-hulk of a ruin. But this too felt bleak. Just beside the Boxpark was a large digital picture of the world to come: the new development was to be called Elephant Park, and flats were officially for sale. Old London burnt up, purified by fire, making way for the boxy corporate design of condos and flats, soon to be home to white-collar workers, low-level execs, those trying to get a rung on the property ladder. A bastion of healthy living: a gym, rooftop gardens, a children’s play area – residents’ access only.

Eventually the Walworth Road unjammed, and the bus turned on to one of the small roads heading south. Ads for Elephant Park continued for another half-mile or so: large, digital illustrations of the bright, white redevelopment scheme. But the advertisements disappeared as soon as we reached the Aylesbury Estate, where a good portion of passengers alighted. I was always fascinated by the Aylesbury when I passed it on this bus: I knew it as one of the most ‘notorious’ estates, not to mention the largest social housing project in Europe, a great grey city unto itself, where Tony Blair made his first speech as Prime Minister, promising to bring prosperity to Britain’s ‘forgotten people’. But I recognized it from somewhere else, too. Television. That old Channel 4 ident, in which a camera pans slowly out onto one of the balconies, surveying the bleak ruin as a large number 4 arranges itself in the center of the screen. The estate doesn’t really look like this, of course. The Channel 4 film crew brought along a few props when they filmed this little clip: plastic bags, wet washing lines and empty lager cans were placed in the shot for effect. The satellite dishes dotting the windows were added later, in post-production.

Eventually the Walworth Road unjammed, and the bus turned on to one of the small roads heading south. Ads for Elephant Park continued for another half-mile or so: large, digital illustrations of the bright, white redevelopment scheme. But the advertisements disappeared as soon as we reached the Aylesbury Estate, where a good portion of passengers alighted. I was always fascinated by the Aylesbury when I passed it on this bus: I knew it as one of the most ‘notorious’ estates, not to mention the largest social housing project in Europe, a great grey city unto itself, where Tony Blair made his first speech as Prime Minister, promising to bring prosperity to Britain’s ‘forgotten people’. But I recognized it from somewhere else, too. Television. That old Channel 4 ident, in which a camera pans slowly out onto one of the balconies, surveying the bleak ruin as a large number 4 arranges itself in the center of the screen. The estate doesn’t really look like this, of course. The Channel 4 film crew brought along a few props when they filmed this little clip: plastic bags, wet washing lines and empty lager cans were placed in the shot for effect. The satellite dishes dotting the windows were added later, in post-production.

The bus carried on past Burgess Park, through the strange residential area between the Walworth Road and the Old Kent Road. We passed rows of old Victorian terraces, a few smaller estates and a handful of new Elephant Park-style condominiums. But as we rode, I noticed something strange. Something was missing from my journey. The announcements – that was it: the bland, computerized female voice that announced each stop had ceased. The journey felt somehow empty without her.

But why? I’d always found it a bit strange, that voice. A bit OK Computerish. Fitter. Happier. More productive. Strange, too, to know that its provenance is a real person, and not a digital automaton – a computer program with RP pronunciation – as I once thought it was. Her name is Emma Hignett. Born in Durham, Emma gave up her dream of being a dancer when she was in her 20s and decided to pursue a job in radio, instead. People had always complimented her on her voice, and she found success as a traffic reporter somewhere up north. Eventually, she moved on to a co-hosting slot on Capitol Gold’s breakfast show in London. But her big breakthrough, of course, was the London Buses. The iBus electronic system came into effect in 2006, mapping and tracking the thousands of buses that drive up, down, across and around London every day. TFL wanted a female voice to announce each stop, and after a brief search, they came across Ms Hignett’s perfectly unthreatening mechanical-staccato voice. Today, she occupies a space in the collective consciousness of most bus-travelling Londoners. Think about the way you hear her voice whenever you walk past a familiar bus stop. Aldwych, alight here for Royal Courts of Justice. Is it tragic that the woman who dreamt of making art with her body – being a dancer – ended up as a disembodied voice? And not just that, but the voice of a new, technologically advanced London – a floating geist of corporate hegemony. Something about her tone, those dulcet recitations – perfect for the type of corporate advertising that would come to be her bread and butter – paired surprisingly well with Elephant Park, those digitized images of corporate architecture. As the bus pulled over to my stop, I imagined the future residents of Elephant Park (as well as the future residents of the new development on the road just around the corner from my house, where the 343 burned to bits that day four years ago) all speaking in her voice. Walking in their parks. Swimming in their indoor pools. Enjoying glasses of white wine on their balconies. And I wondered where my former neighbors would end up. The old men and women who came outside to look at the burning bus that day. Perhaps they’re set to go the way of the buses. ‘Best to let it burn itself out,’ the fireman said to me that day. ‘No point in fighting it.’

The bus carried on past Burgess Park, through the strange residential area between the Walworth Road and the Old Kent Road. We passed rows of old Victorian terraces, a few smaller estates and a handful of new Elephant Park-style condominiums. But as we rode, I noticed something strange. Something was missing from my journey. The announcements – that was it: the bland, computerized female voice that announced each stop had ceased. The journey felt somehow empty without her.

But why? I’d always found it a bit strange, that voice. A bit OK Computerish. Fitter. Happier. More productive. Strange, too, to know that its provenance is a real person, and not a digital automaton – a computer program with RP pronunciation – as I once thought it was. Her name is Emma Hignett. Born in Durham, Emma gave up her dream of being a dancer when she was in her 20s and decided to pursue a job in radio, instead. People had always complimented her on her voice, and she found success as a traffic reporter somewhere up north. Eventually, she moved on to a co-hosting slot on Capitol Gold’s breakfast show in London. But her big breakthrough, of course, was the London Buses. The iBus electronic system came into effect in 2006, mapping and tracking the thousands of buses that drive up, down, across and around London every day. TFL wanted a female voice to announce each stop, and after a brief search, they came across Ms Hignett’s perfectly unthreatening mechanical-staccato voice. Today, she occupies a space in the collective consciousness of most bus-travelling Londoners. Think about the way you hear her voice whenever you walk past a familiar bus stop. Aldwych, alight here for Royal Courts of Justice. Is it tragic that the woman who dreamt of making art with her body – being a dancer – ended up as a disembodied voice? And not just that, but the voice of a new, technologically advanced London – a floating geist of corporate hegemony. Something about her tone, those dulcet recitations – perfect for the type of corporate advertising that would come to be her bread and butter – paired surprisingly well with Elephant Park, those digitized images of corporate architecture. As the bus pulled over to my stop, I imagined the future residents of Elephant Park (as well as the future residents of the new development on the road just around the corner from my house, where the 343 burned to bits that day four years ago) all speaking in her voice. Walking in their parks. Swimming in their indoor pools. Enjoying glasses of white wine on their balconies. And I wondered where my former neighbors would end up. The old men and women who came outside to look at the burning bus that day. Perhaps they’re set to go the way of the buses. ‘Best to let it burn itself out,’ the fireman said to me that day. ‘No point in fighting it.’  'The Old Dogwheel' at the Castle of St Briavel, Gloucestershire, illustrated in E.F. King, Ten Thousand Wonderful Things (1890)[/caption]

This is mere conjecture, however, because, although common throughout the British Isles in the 18th century, by 1850 the turnspit dog had become a curiosity, and by the Great War, the breed had disappeared completely. A technological, rather than ethical shift seems to have been responsible for their demise: an American campaign for a ban on turnspits in the 1870s succeeded in changing public attitudes to the use of these dogs, but had unintended consequences when animal rights activists discovered goats, donkeys and even African American children had replaced them in kitchens unable to afford more modern equipment. Such concern for animal welfare was unusual in a period when few could afford to keep an idle pet for their own amusement, and dogs were considered little more than a cheap utensil, to be used, abused, and then discarded once a more efficient alternative came along.

Given the importance of spit-roasted meat to British cooking, the appearance of the automated spit turner at the end of the 16th century must have seemed like a culinary miracle, and as the technology improved in the 17th and 18th centuries, these mechanical jacks moved from luxury purchase to culinary necessity. Though there are records of turnspit dogs operating into the early 1900s, in many cases they were retained for their rarity value – there’s some evidence the last of their kind were even hired out as attractions.

With its unfortunate looks, and understandably ‘morose’ temperament, however, the breed was never going to make the transition to favoured pet. Queen Victoria is said to have kept three retired ‘turnspit tykes’ at Windsor for her amusement, but this particular royal fad didn’t catch on with her subjects, and the distinctive, bandy-legged beast quietly breathed its exhausted last just as the 20th century was getting into its stride. The real sadness is not that this poor, put-upon creature has been rendered obsolete by a machine, but that it was so little valued in its time that it's almost as if it never existed at all. Few who enjoyed the fruits of its labours troubled to record the brief life and times of the turnspit – but let us hope they at least threw Wilf's ancestors the odd bone.

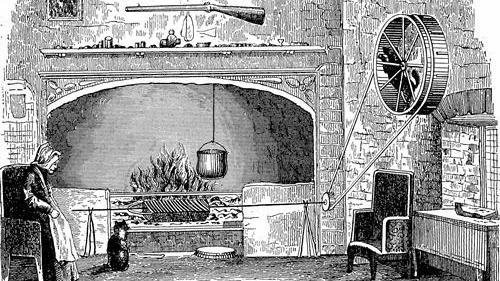

'The Old Dogwheel' at the Castle of St Briavel, Gloucestershire, illustrated in E.F. King, Ten Thousand Wonderful Things (1890)[/caption]

This is mere conjecture, however, because, although common throughout the British Isles in the 18th century, by 1850 the turnspit dog had become a curiosity, and by the Great War, the breed had disappeared completely. A technological, rather than ethical shift seems to have been responsible for their demise: an American campaign for a ban on turnspits in the 1870s succeeded in changing public attitudes to the use of these dogs, but had unintended consequences when animal rights activists discovered goats, donkeys and even African American children had replaced them in kitchens unable to afford more modern equipment. Such concern for animal welfare was unusual in a period when few could afford to keep an idle pet for their own amusement, and dogs were considered little more than a cheap utensil, to be used, abused, and then discarded once a more efficient alternative came along.

Given the importance of spit-roasted meat to British cooking, the appearance of the automated spit turner at the end of the 16th century must have seemed like a culinary miracle, and as the technology improved in the 17th and 18th centuries, these mechanical jacks moved from luxury purchase to culinary necessity. Though there are records of turnspit dogs operating into the early 1900s, in many cases they were retained for their rarity value – there’s some evidence the last of their kind were even hired out as attractions.

With its unfortunate looks, and understandably ‘morose’ temperament, however, the breed was never going to make the transition to favoured pet. Queen Victoria is said to have kept three retired ‘turnspit tykes’ at Windsor for her amusement, but this particular royal fad didn’t catch on with her subjects, and the distinctive, bandy-legged beast quietly breathed its exhausted last just as the 20th century was getting into its stride. The real sadness is not that this poor, put-upon creature has been rendered obsolete by a machine, but that it was so little valued in its time that it's almost as if it never existed at all. Few who enjoyed the fruits of its labours troubled to record the brief life and times of the turnspit – but let us hope they at least threw Wilf's ancestors the odd bone.