On October 24, 1875, the New York Times published a notice on behalf of the Royal Aquarium Society, announcing the birth of a grand project – and seeking American investors. The Royal Aquarium would occupy a prime site in the centre of London, facing Westminster Abbey across Broad Sanctuary: a living microcosm at the heart of the Empire that ruled the waves. Well-stocked tanks would line a vast hall the length of a football pitch, rising to a long roof of Rendle’s patent glass running the length of the building. Everything would have its place in the metropolitan kingdom of the deep. Touting not just sea-life, but ‘reading-rooms’, ‘galleries’, ‘lectures, and conversazioni, &c.’, the transatlantic prospectus for an aquatic future builds up to a watery fantasy of moral improvement, directed at readers of the paper of record:

The playful porpoise and the sprightly shrimp will here be taught that they have respectively higher duties than to plunge in a purposeless manner, and to be formed into sauce for turbot. It will be their proud privilege to aid in the education of the masses – to teach the great majority something of the inner life of the ocean.

The accents are unmistakably Victorian; the pitch recognizably modern. The education of the masses may have yielded to more contemporary aims, but the grand project has always been a good way of coating someone’s savvy investment with the lacquer of public spirit, especially if you can count on establishment support. There were even celebrity backers: Millais was to curate the art gallery, and Arthur Sullivan was on the board of directors.

The Aq, as it came to be called, seemed like a safe bet. In the years after the opening of the London Zoo Fish House in 1853, the fascination for all things aquatic and amphibious had developed into a craze. ‘We shall not exaggerate greatly,’ The National Magazine declared in 1857, in a review of no fewer than eight books on the subject, ‘if we say that everybody nowadays has an aquarium.’ As large-scale aquaria were built across Europe, from Naples to Manchester, they became important social spaces. In Tennyson and His Friends, for instance, the son of the poet laureate recalled a visit he had made to the Fish House in the company of his famous father:

All went well for some time until we went into the Aquarium, and he became greatly absorbed in the sea monsters, when I heard a whisper in the crowd, ‘That’s Tennyson,’ and knew that in another minute he would be surrounded; so I suddenly discovered that the heat of the Aquarium was unbearable and carried him off unwillingly to a quieter part of the gardens.

Communing, no doubt, with the spirit of the Kraken, Tennyson risked becoming an exhibit himself, caught in the visual net woven through a space that encouraged inquisitive gazing.

*

The popularity of the aquarium bespoke a widespread interest in natural history – an interest consolidated at the end of the 1850s by the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species – but it also lent itself to a comfortable rhetoric of society held in balance. The English middle classes eagerly made way in their homes for domestic tanks stocked with anemones, molluscs and the occasional guppy; learning about their miniature biosphere, these enthusiasts of the aquarium found themselves speaking a language of equilibrium, of water and waste, of light and hygiene, that tallied with wider Victorian projects of social and structural intervention like Charles Booth’s poverty maps and Joseph Bazalgette’s sewers. Imported into the drawing room, the aquarium embodied the fantasy of an ideal, harmonious Empire in which every class and race would contentedly play its appointed part in a minutely calibrated system constituted under the guiding hand of the almighty and His establishment stewards.

Where the ideal home aquarium was held in balance, the larger public aquaria were able to engage a different, no less popular, social metaphor. Writing in The Athenaeum, the aquarium impresario W.A. Lloyd (who had designed aquaria in Paris, Hamburg and Hanover, as well as the one at the Crystal Palace) stressed the extraordinary new equipment for the circulation of water through the Royal Aquarium’s many tanks. Circulation, that marvellous process animating Victorian thought from the library to the Bank of England, from Dombey and Son to Dracula, would ensure well-being in the Westminster deeps. Moving from the display tanks into a series of holding vats, the water would at length return, aerated, bringing the stuff of life to the creatures behind the plate glass. Lloyd described the process as ‘circulation without change’: an idea that would have appealed to Tennyson.

When the building was completed, its champions hoped that other forms of circulation would improve social cohesion, as well as guaranteeing financial success. Prince Alfred, speaking as guest of honour at the opening ceremony, caught the prevailing mood:

The extensive aquarium, which is the main object of this institution, cannot fail, if properly directed, to stimulate the love of natural history and the acquirement of scientific knowledge. The access to a useful reading-room, the daily performance of good music by a well-chosen orchestra, the periodical exhibition of such collections of paintings as we see around us – these are agencies which cannot but exercise a most beneficial influence in refining and cultivating the public taste.

Appropriately, given its location a stone’s throw from Parliament Square, the Royal Aq wasn’t just a venue for admiring sea-life. It was a temple of self-improvement and a hub of the Victorian communications network. It had a telegraph office. It even had a link to the division bell in the Palace of Westminster, so that any piscophile Member of Parliament could stroll through the grand hall without fear of missing a crucial vote. Not only water and oxygen, but all sorts of people, from MPs to working-class day-trippers were supposed to pass through the Aq’s watery arcades; its glass roof would enclose an archive of knowledge through which matter, information, and citizens could circulate in well-regulated flows.

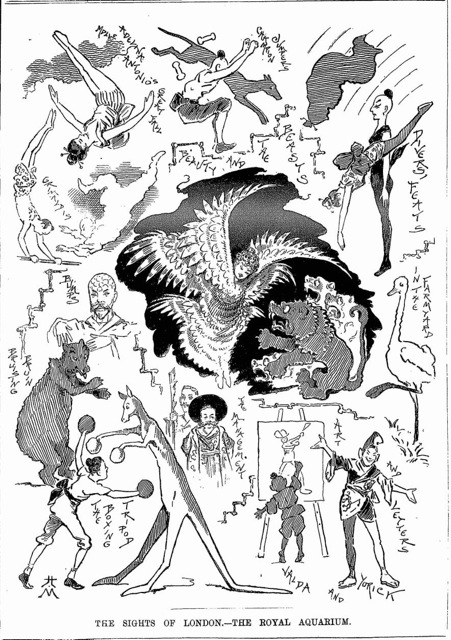

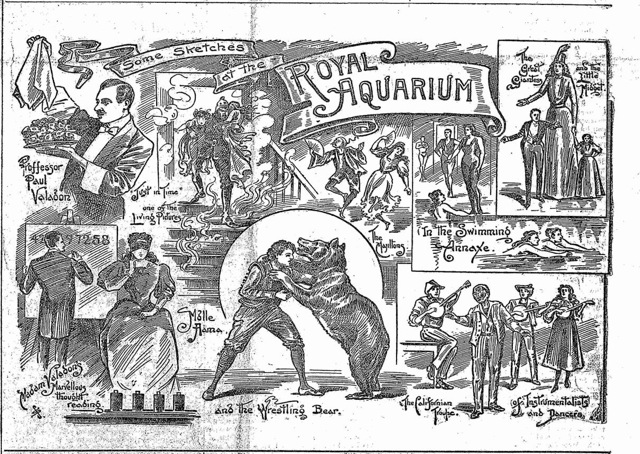

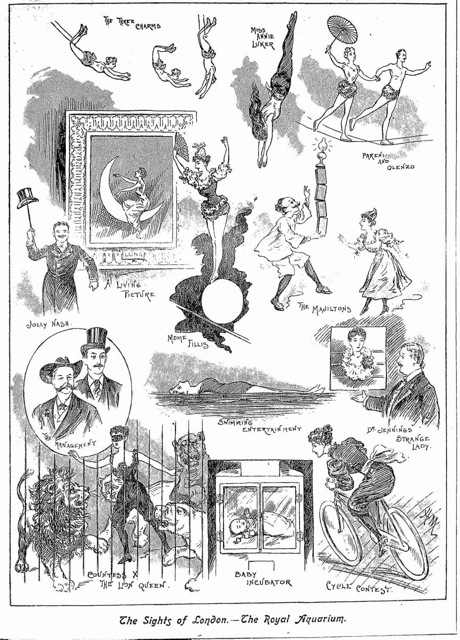

And yet, despite the investors’ best intentions, something went wrong. The fad ended. It wasn’t a lack of water that failed to keep the aquarium afloat, but of an equally necessary circulating substance: capital. Entertainment at the moribund aquarium was turned over to William Leonard Hunt, a variety performer better known at the time as The Great Farini. Concerts and exhibitions were gradually replaced by an ongoing series of dog shows, freak shows and stunts – but precious few fish. In 1877, the Aquarium hosted the world’s first Human Cannonball: a fourteen-year-old girl propelled by a spring mechanism designed by Hunt himself.

There was simply more money in the circus than in sea life. The trained eye of the naturalist stood no chance against more populist ways of looking. Late in the century, one humorist would remark that the chief use of the glass exhibit tanks ‘seemed to be for young ladies to stand at one side of them, and young gentlemen to stand opposite the young ladies, gazing at each other furtively through the glass, and pretending to look at a slumbering baby crocodile.’

In 1885, The Era, which as the preferred showbiz newspaper of the time had sung the praises of the venue at its opening, gave the predictable reason for the failure of its high ambition: to pay the shareholders’ dividend, it had been necessary ‘to abandon the lofty ideals propounded in the prospectus issued to the public when the Aquarium was in an embryonic stage.’ The Aquarium’s listing in the 1897 edition of Dickens’s Dictionary of London (compiled by the novelist’s son) suggests the scale of the problem:

Not only were the plans of the managers in an inchoate state, but the tanks were without tenants, and wholly unfit for their reception. The aquarium without fish became a standing joke … After some time the tanks were filled, and energetic management provided attractive entertainments of a music-hall type.

Sure enough, the Dictionary carries an advertisement in its back pages for the Aquarium, where the ‘usual programme’ includes ‘3.15.—grand variety entertainment’, followed by ‘recital on great organ’ and, in the evening, ‘8.30.—second unsurpassed variety entertainment’. Although good arguments were made in favour of cheap, regulated entertainment for the masses, it was hard to square the ambitious promise of the pedagogical porpoise with the more sensational attractions of Mr. Harry Phillips’s Living Mythological Mermaid (‘Half Beautiful Woman, Half Fish’), or of Zaeo, a lady trapeze artist whose canny promoter had caused a stir with a risqué poster campaign. The refusal of the licensing authorities to allow dancing on the premises provided inspiration for one balladeer in the light press, who envisaged a racy coupling of fish and flesh:

Will lively crabs the can-can dance,

And learn to bounce and royster?

Or flounders wobble to thy strains,

Accomplished whistling oyster?

*

‘If we attempt to collect and to keep marine animals alone in sea-water,’ Philip Henry Gosse had written, ‘however pure it may have been at first, it speedily becomes offensively fetid, the creatures look sickly and rapidly die off, and we are glad to throw away the whole mass of corruption.’ Deprived of its improving purpose, its resources slowly diminished by the siphoning off of the original investment, the Aq became known not for the miraculous creatures of the deep, but for the scantily-clad acrobats of the air. Before he was known as a novelist, the young Joseph Conrad would stroll up from his dull caretaker’s job in a warehouse on the Thames and spend summer evenings watching a show, or wandering the Aquarium promenade with his friend Adolf Krieger. Later, in The Secret Agent, he would remember fin-de-siècle London as a habitat for ‘queer foreign fish’: ‘a slimy aquarium from which the water had been run off.’

It’s a lesson worth remembering: how quickly ‘higher duties’ and ‘the education of the masses’ can give way to the more pressing matter of return on investment. The Fish House at the Zoo closed in 1890; shortly afterwards, the tanks at the Crystal Palace aquarium were converted into a makeshift monkey-house. At the Royal Aquarium itself, air, light, and fresh water were no match for dwindling box-office receipts, and, having outlasted all recollection of early promises about the social benefits it could bring to Londoners, the building faded away into a venue for freak-shows and circus acts. Long after its demolition in 1903, one commentator recalled that ‘the poor, gloomy old place … was in its last days one of the horrors of London. With its dingy interior and derelict tanks, in one of the last of which survived a melancholy crocodile, any more depressing resort was not to be imagined.’

Today’s London Aquarium stands just across the Thames, occupying the old premises of the Greater London Council on the South Bank, where one sort of fishy business has replaced another. From its neighbouring attraction, the London Eye, shoals of tourists gaze out across the city. In 2003, the Saatchi gallery moved into premises upstairs, bringing along Damien Hirst’s mouldering shark. Its insides having rotted away, the work was by then no more than a piece of conceptual taxidermy: a simulacrum of the ocean’s most successful predator. Close kin to the melancholy crocodile, there it floated, enclosed in its vat of stagnant formaldehyde, conjuring dreams of the open sea.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.