My latest list is a to-do list. I used bullet points (to add a special air of organisation) and ranked each item in order of importance (ditto). It is a short list and I have done none of the things on it. It is at once a useful visual prompt, an expression of my wishful thinking, and a permanent reminder of my failure. We all (or nearly all) write lists of some kind, but what lies between the lines, what stories are hidden in these humble slivers of life?

From the Ancient Greek Seven Wonders of the World, through Homer, the Bible, the encyclopaedias of the Middle Ages, the 16th-century classifications of nature and the designs of the Scientific Revolution, on to the horrific death lists of Nazi Germany and right up to today’s note-taking apps, we have long noted down the everyday, the monumental and the necessary. Lists give us a sense of purpose and a structure, a means to lasso our grief, madness and dreams with neat lines. They are an expression of the Hegelian notion that we live authentically when we are responsible for creating the order by which we live. These lists hold our chaos, they become a bridge between the moment of feeling and the moment of doing, and make sense of our skittering thoughts.

But they can also restrict us, confining the scope of our experience and acting as a buffer between ourselves and taking the leap into the void. Making a travel itinerary may seem a sensible way of preparing for a trip, but it can also stifle the spontaneous flow of travel. And here lies the inherent paradox: a list is an attempt to control our world, and proof that this is unachievable. There is an art and a science, a folly and a clarity that is unique to list-making.

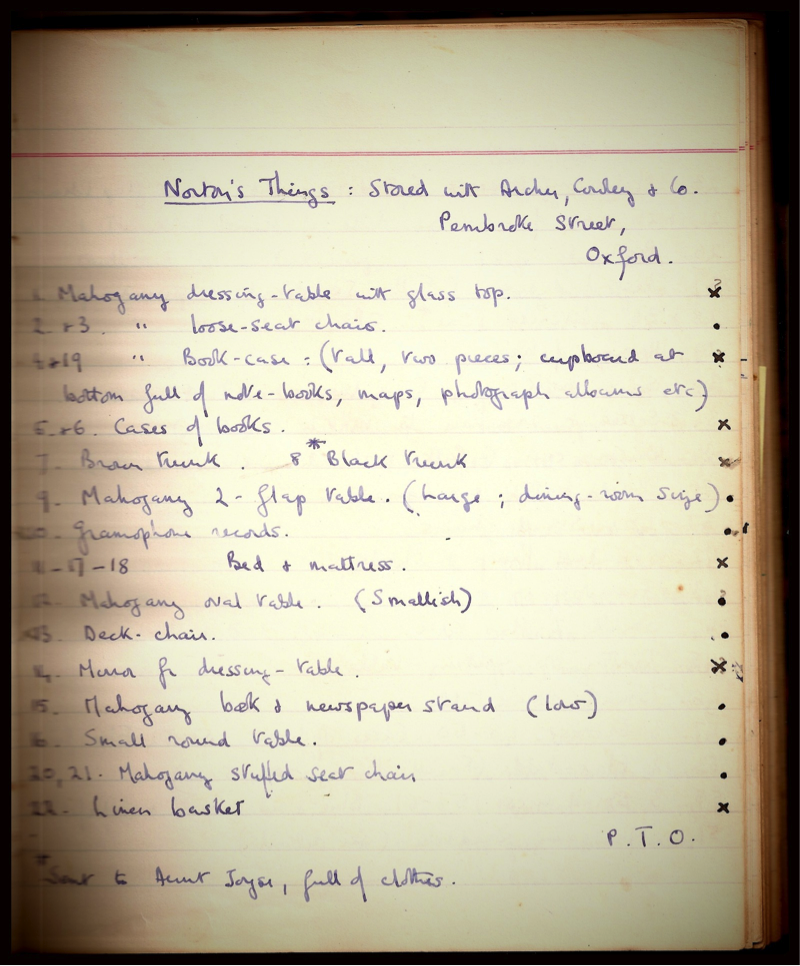

I can trace my own list-making tendencies to a battered journal of lists written by my grandmother, Elisabeth, who died in 1957 aged 42. Her story has always fascinated me (the bullet fired by Chinese bandits that my grandfather dug out of her forehead with a key, the glamorous world of diplomacy she inhabited, the cancer that killed her) and I began to piece together her life through these fragments, enveloped in the world of a woman I never knew. Entitled ‘Norton’s Things’, the list above looks on first glance like the other inventories of furniture and possessions in Elisabeth’s book of lists, but its matter-of-factness belies the intense sorrow at its root. It itemises the things left in the flat belonging to her beloved brother Norton.

In March 1941 Norton climbed into his empty bath wearing a pair of pyjamas, covered himself with an overcoat and took a lethal overdose of sleeping draught. His body remained undiscovered in its strange cast iron coffin for several days. I know all these things from an inquest report that I alone have seen. An unnerving sense of being an intruder creeps over me as I read this report, alongside Elisabeth’s list, on a train to Eastbourne one murky afternoon. A list is a conversation with oneself, and some have a prayer-like quality; they are not for others’ eyes. Yet these snippets reveal so much about the way we interact with our world — our possessions, hopes, fears — that I am compelled to keep reading to find the story that lies within these pieces of paper. In this list I find a man I knew little about, and a death that raised more questions than it answered.

Elisabeth made many lists but this one must have been heartwrenching. I find it on a page previously headed ‘Glass’, the gentle itemising of her glassware abruptly interrupted by her brother’s death. Normality is suspended here. The list runs onto two pages, the second headed ‘Details concerning opposite list’. That heading establishes a distance between the pain Elisabeth was suffering, and also feels like an intake of breath, a drawing-in of sorrow in order to reconfigure it into something practical.

Within the dots, emphatic crosses and smudges, I find another layer of grief: the things Elisabeth is unable to control, the mess of life seeping onto the page, her emotions ebbing with the ink. Perhaps the crosses are asterisks to mark the things still to be sorted; but a cross also symbolises a negative, the headshakes of disbelief, the ‘No!’s, the sadness she can’t pack away. The list feels stilted and heavy. It is a catalogue of loss. I imagine Elisabeth bravely writing on though the words were breaking her.

The act of noting items in a list gives them permanence, allowing them to exist in a different form. I am reminded of artist Michael Landy who itemised and then destroyed every one of his possessions in an installation entitled Breakdown. What this meticulous dismantling of a life revealed was the impossibility of nothingness. Landy’s possessions were destroyed, yes, but they also lived on in the catalogues Landy had prepared for Breakdown, and in the dust they became. Our possessions express our identity, the fluid story of self that we wish to present to the world. In writing a list of possessions we are recording these symbolic identity statements, and also capturing the feelings and emotions attached to the objects listed. For Elisabeth, unravelling the life of her dead brother, these possessions were Norton: in making this list she was preserving him in a different state, and it is this impression that I want to decipher.

What answers can I find in the list of Norton’s Things? One suitcase is stated as containing one pair of pyjamas, one pair of pants and two suits, suggesting Norton didn’t even unpack after returning from a holiday he had taken with Elisabeth the week before his death. An overcoat is also listed here, maybe the one in which he shrouded himself after climbing into the bath — did someone repack this after he died, or did he choose a different coat? How would someone choose the coat under which they wish to die? Did he want to be comforted by soft fabric, or wrap himself in something more solid to shield him from what was outside? Our clothes are a second skin and what remains after they have been removed is an after-image, a shadow-self. Norton emerges, faintly, slowly, through these shadows.

I note with interest that he owned three brooms, which seems unusual for a man of his class (who certainly would have had domestic help) living in a small flat. Is this evidence of a fastidious nature? The bath seems symbolic, a container for his body but also a way of controlling any unpleasant physical consequences of an overdose. The brooms, along with the way he chose to die, point to an obsessive concern with cleanliness and order. I feel sure Norton would have been a list-maker. I imagine the flat was left tidy and organised, everything in order.

Norton is a mysterious figure in our family history. Families may control problematic issues by avoiding the subject altogether, a kind of complicit secrecy that enables normal relationships to continue. It is clear from Elisabeth’s diaries and letters that Norton didn’t ‘fit in’ and was never comfortable in his skin. There are family rumours about autism, an eating disorder and his sexuality. In examining this list of his possessions, I have a sense that some things have been left out. Elisabeth noted that she took some ‘oddments’ and one attaché case, and I wonder whether she had to hide anything that she wouldn’t wish her family to find. Elisabeth writes in her diary of Norton’s pink dressing gown, a flamboyant article of clothing that contrasts with the rather plain items in this list. I wonder what shadow this contained, and why it is not here with his other possessions. What is excluded from a list can be as significant as what is included; lists help us to remember, but we must not overlook the importance of forgetting. Some information is too painful (or simply not important enough) to be remembered, and a list here can act like a sieve, filtering out what will be stored or discarded. If Norton was indeed gay, at a time when this was not only socially unacceptable but also illegal, we can only guess at how this contributed to his struggle to stay in the world. What Elisabeth wanted to remember is the brother who is encoded in her list; what is left out is another, more complex, part of their story.

Norton’s death must have been almost unbearable to Elisabeth, but through the routine task of recording her brother’s things she found a way to regulate and control her grief. She found a sense of order in the wake of something in which she could find no rationality or reason. In the depths of sorrow a simple list can be a methodical framework with which we support ourselves while the ground cleaves beneath us. The act of fixing the details of life on paper enables the gathering-in of loss, the re-shaping of our emotions from incomprehension into meaning and action. But it can’t, ultimately, keep us from death.

When someone dies the bereaved walk a wire, balancing between getting on with life and keeping close the person they have lost. Picture a tightrope walker. Each delicate, spellbinding step moves him forwards but also away from the safety of where he started. There is a point of suspension in the middle, equidistant from both points and it is here I find Elisabeth, in this impossibly difficult place for someone in grief, moving from the deceased being part of their world to a new way of existing without them. Elisabeth’s list of ‘Norton’s Things’ is her wire.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.