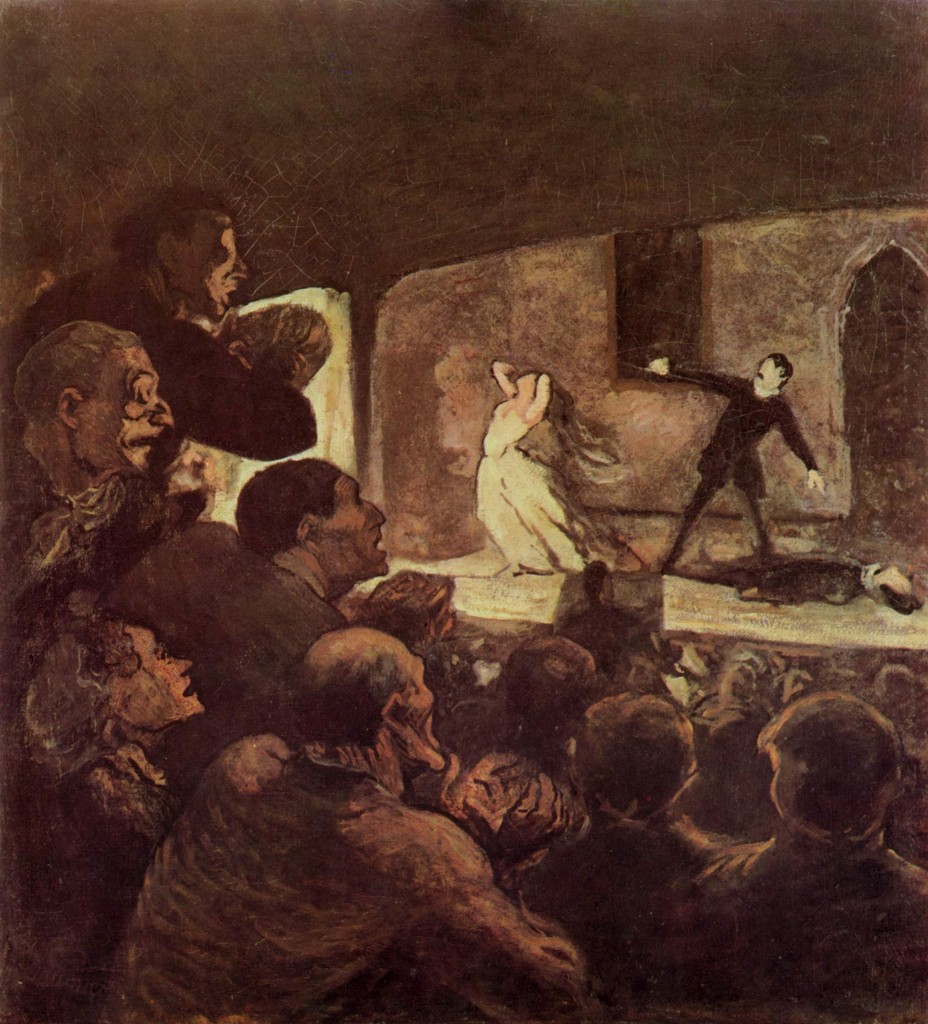

Honoré Daumier, Le Mélodrame, (c1860-64)

Honoré Daumier, Le Mélodrame, (c1860-64)

In Daumier’s Le Mélodrame, a heaving crowd watches the climax of the play. On stage, a woman swoons. The love triangle is resolved, a man lies dead. Meanwhile, outside, Hausmann’s plan is taking shape. Homes as well as playhouses are coming down, streets opening up in new lines of sight and force. Wide streets make manageable spaces. Room for artillery, for crowd-control. But this is a dark place, full of the energy of the audience. The Gaîeté, maybe, or the Théatre de Porte Sainte-Martin. The wrecking crew is on the way, right behind the stagehands. This city, Paris, is an old set, too, waiting to be struck for the next opening night. The Paris Commune is only a few years away. But here in the darkness, a man is leaping up — or better say he is caught up — on his feet. He isn’t part of the crowd any more: he’s part of the play.

A fine thread of attention holds him there. What can he do? Nothing much. Stand and watch. Hands clasped in front of him, elbow flung out over the head of his neighbour with the cropped hair who flinches away, his eyes never leave the stage. The man with the short hair rises a few inches from his seat. A woman jostles from behind, irritated that her view has been blocked. She lifts her head, straining. Beside her, another man — her husband? — leans forward. A little crooked, a little gaunt. Not so mobile. Not a romantic lead. He has raised his hands as though in supplication or in prayer. The light catches them. They glow, warmed by something in the scene. Something to hold on to, something accepted from the woman falling away.

Already the theatre is a place for keeping an eye on the crowds. Are they over-excited? Are they too tightly packed? Are passions running too high? But here we are, cut off from all of it. If you have ever been an unbeliever at a religious service, you know this feeling: the polite, affectless guilt of watching a congregation at prayer.

*

Walter Sickert, The Old Bedford (1894-95)

Walter Sickert, The Old Bedford (1894-95)

Unlike Daumier’s theatre, there isn’t any rapture in Sickert’s music hall. No transport. These are relaxed faces, interested yet dispassionate, looking down at a chorus line, at a variety act, at Marie Lloyd singing A Little of What You Fancy. The man in the second tier — is he coughing? Yawning, more likely. Only the boy at the front, leaning his chin in his hand, seems lost in the performance below. The shock of orange on the pillar dividing the scene between the watching audience and its pale reflection. The impossible specular geometry. The gilt. Designed to amplify space, the mirror, as Sickert paints it, does the opposite. It’s a tightening of the noose. To the rear, at the right, the figure in the top hat looks out of place until you notice the second reflection of the ceiling vent and realise that he’s a mirrored image too, the spectre in the gallery. Beloved of mad-eyed Ripperologists, Sickert’s Camden Town Murder paintings have thieved something from the battered gleam of these music-hall moments, which are far more intimate and more disturbing than any crime scene. It’s here, shockingly in public, that you find Sickert’s real perversity. The cold detachment from the object of desire. Second order voyeurism. The contrariness that prefers to watch watching. A heretical artist chooses to avert his gaze from the spectacle, eyes on the crowd instead of the stage, painting not the naked flesh of the urban poor but faces caught in fantasy.

*

James Jarché, Cinema Audience Pictured Using the Ilford Infra-red Process (1932)

James Jarché, Cinema Audience Pictured Using the Ilford Infra-red Process (1932)

Surveillance footage is as old as film itself. Lumière no sooner perfected his cinématographe than he pointed it at his employees. In La Sortie des usines Lumière, a stationary camera frames the gate of the Lumière brothers’ Lyon factory as workers, mostly women, emerge. In the spring of 1895, the camera inaugurates a new kind of space and a new kind of time. A dog runs alongside a man on a bicycle. A woman lingers indecisively before walking out of the frame to the right. A man waves a sheaf of papers. Gossips linger; young lovers rush off home. From now on, in principle, every gesture can be isolated, replayed, monitored. Like any good security firm, the Lumières know how to turn their proprietary technology into hard cash: by the end of the year their picture show is ready for paying audiences.

Borrowing the taboo felt so strongly in Sickert, there’s still something disturbing about being watched as we watch. In the early 1930s, the Fleet Street photographer James Jarché managed to snap the audience at the Carlton Theatre — slumming it now as the Haymarket Cineworld — using a set of infrared lamps mounted in the gallery. Infrared photography had been developed during the Great War as a tool for aerial reconnaissance and survey mapping; like most military technologies it slipped more easily into civilian life than returning soldiers did. Sensing potential, companies like Kodak and Ilford started experimenting with improved chemical dyes, making photographs like Jarché’s possible. By the early 1940s, sociologists working for J Arthur Rank — Britain’s largest cinema company — were taking infra-red exposures of Saturday matinees in order to find out how children in the audience reacted to the action on screen.

*

Colin Moss, Gaumont Cinema Audience (1948)

Colin Moss, Gaumont Cinema Audience (1948)

In The Midnight Bell, Patrick Hamilton’s novel of 1929, a young waiter takes his girl to the pictures. Under the gaze of the vigilant uniformed usher, Ella and Bob grope their way through a haze of Orientalist décor to their seats:

At last they were settled. In a few moments they were a part of the audience. That is to say their faces had abandoned every trace of the sensibility and character they had borne outside, and had taken on instead the blank, calm, inhuman stare of the picturegoer — an expression which would observe the wrecking of ships, the burning of cities, the fall of empires, the projection of pies, and the flooding of countries with an unchanging and grave equanimity.

Hamilton’s picturegoers are familiar: blank and grave, solitary and identical, suasible and insensitive. Twenty years later, they still look that way in Colin Moss’s Gaumont Cinema Audience, where the stolid figures of the English public settle heavily into red velvet, eyes on… what? Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol, maybe? Or The Red Shoes? Moss had worked as a camoufleur during the Second World War, designing disruptive patterns to hide buildings and infrastructure from bomber raids, merging targets into the landscape. This painting records a different kind of absorption: that of a weary, ration-fed audience in silver screen fantasy. Three or four bodies are picked out in profile by the projector’s reflected light, slouching down, expressionless. There’s nothing to say about them, no more than about the out-of-focus crowd behind them. They are self-contained, fixated on the same thing. Captivated in isolation, glued to the screen.

*

We’re still watching. Filming to catch anyone trying to film the film. In 2010, a trade journal reported that a company called Aralia Systems was working with scientists at the University of the West of England to develop infrared scanning systems for capturing audience reactions and processing them into data. Aralia’s website describes the company as being for hire to ‘public, private and government organizations with mission critical security requirements’. Its partner company has a press release on its website which warns (or promises) that ‘cinemagoers may one day be recorded for market research using 2D and 3D imaging technology’. Market research as an endless feedback loop — producing only noise.

Mirrors in mirrors; screens on screens. CCTV in operation for your protection. Even this false motto has been dropped in favour of anti-piracy warnings. No one pretends this camera is there to protect you. It’s there to protect the film from the destructive potential of an audience armed with its own cameras, as though those occult beliefs for which European technologists scoffed at the savage were suddenly reflected on the controllers of the commercial image. Watch out. The camera can capture your soul.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.