Reality is hard to fake. While it is relatively easy to create a visual simulation of a static object, it is almost impossible to reconstruct convincing environmental phenomena and atmospheric effects. Creating the illusion of water in motion requires an extensive repertoire of artistic skills: the ability to observe and represent the shifting geometries of line, surface, and volume, while rendering the surface reflections of light, transparency and fluidity. From Chinese landscape painters to contemporary digital animators, these demands have made the virtual representation of rivers a true test of visual craftsmanship. According to classical Greek aesthetics, mimesis – the imitation of the physical world – stands for beauty and truth. Yet this does not take into account the relentless evolution of visual language: from drawing to printing, moving image to Internet mapping. Rivers – both real and virtual – allow us to record the accelerating rate of technological change; as Heraclitus says, nobody steps in the same river twice.

EASTENDERS The line of the Thames is the focus of the EastEnders’ title sequence, a continuously changing cultural artefact through which recent ways of seeing London can be read. The famous opening credits feature two simultaneous motion picture effects – the slow zoom out coupled with the rotating frame (essentially the exact opposite of newspaper headline shots from black-and-white films such as Citizen Kane).

The line of the Thames is the focus of the EastEnders’ title sequence, a continuously changing cultural artefact through which recent ways of seeing London can be read. The famous opening credits feature two simultaneous motion picture effects – the slow zoom out coupled with the rotating frame (essentially the exact opposite of newspaper headline shots from black-and-white films such as Citizen Kane).

Looking closely, the original pilot sequence is constructed from an aerial photograph of London, pasted onto some cardboard and manually manipulated by BBC special effects crew. The Thames is a uniform tone of cyan, probably the painted underlay that the photograph was pasted onto. London is presented at an oblique angle, which makes the false flatness of the image even more apparent. While the techniques used have changed from analogue to digital, the essential composition of the introduction has changed little in 30 years. The most revealing comparisons between simulation and reality come from artificial renderings of natural effects. In the original opening sequence of 1985, invisible clouds from outside the frame cast shadows onto the city; this airbrushed effect only reinforces the complete flatness of the source image.

The most revealing comparisons between simulation and reality come from artificial renderings of natural effects. In the original opening sequence of 1985, invisible clouds from outside the frame cast shadows onto the city; this airbrushed effect only reinforces the complete flatness of the source image.

Twenty-five years of technology later, the 2010 EastEnders scene is altogether more realistic. London’s parks are much greener, the Thames is a deeper shade of blue, and there is some depth and shadow to the cityscape. Even with the camera zooming out through several layers of clouds, it would not be immediately obvious if it was made with a real or virtual camera.

This illusion is shattered by the late appearance of the title text, which casts an entirely improbable shadow onto London below. Now we read the image as a computer rendering, with simulated light glinting off the surface of the Thames, its digital water painted an iridescent blue and not the muddy green tones that it has in real life.

BURIAL

The Thames runs deep while appearing shallow. Unlike most rivers in major European cities, it rises and falls with the tide, creating a daily change in level of over seven metres. Virtual renderings never attempt to show the sludge-silt riverbed exposed during low tides; in this world, the Thames tide is perpetually high.

The first Celtic settlers of the area did not have the modern luxury of clean illusion. They had to confront a waterway surrounded by swampland, prone to flooding and difficult to bridge. They recognised the need to control the Thames’ protean character, establishing a pattern that successive inhabitants have followed: London buries its rivers with stone and resurrects them with street names (Fleet Street) and spectacles (often televised). The network of waterways still flows through London, forming an invisible web that outlasts any civilisation built over it.

It is fortunate that the Thames forms a perfect meander just as it reaches the Docklands. This hydrological flourish serves as the signature to an otherwise conventional river, a sweeping curve that allows us to identify the city from above. In geography textbooks, we would understand that particular loop as being from the third stage in the formation of ox-bow lakes, just before the erosive force of water cuts through riverbanks on opposite sides of a bend. That process has been temporarily halted by the concrete embankments of the Isle of Dogs, a measure that keeps the ox-bow lake in a state of suspended animation. While urban artifice maintains the line of the Thames, the way we perceive the same river changes.

OLYMPICS

Just like in EastEnders, the Thames is a prominent motif in the televised version of the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony. We start our journey at its source at Thames Head in Gloucestershire, rising up from an underwater shot inside the river itself. From here, we are swept upwards, airborne along through the leafy suburbs to the Olympic Park in Stratford, East London in less than two minutes. Filmic montage allows us to imagine that our journey is accompanied by wandering ducks, British rail passengers, and Gollum-like children gallivanting on the river – all set against a backdrop of Didcot power station in the distance. Suddenly, we cut to Battersea Power Station, skimming the surface of the Thames to the five rings hanging on Tower Bridge.

Fly-through sequences like these are not made by real film crews on helicopters or by remote-controlled drones; they are composite montages of the digital city. Animation studios buy packages of three-dimensional data about London and then program virtual scenes to move through. These short clips are then woven together with live camera footage into seamless simulations. Upon closer observation, you can observe the transitions between digital and analogue realities. Look closely, and the Oxfordshire segment of the sequence is predominantly filmed by a real helicopter flight, sped up to look closer to the computer-generated second half. Tell-tale signs include visual anomalies (flying pigs), time dilation (the hands on Big Ben revolve too quickly), and stunts too extreme for daytime television (flying below bridges). These details are lost on us, who remain disoriented by Hollywood-esque sensory overload of Danny Boyle’s direction to notice their presence.

Inside the stadium in Stratford, it becomes apparent that even in 2012, the problem of how to represent natural effects remains unresolved. Here, simulated physical cotton-candy clouds encircle the ceremony as incidental ornaments to the scene. Instead of being apologetically real, they revel in their overt falsehood.

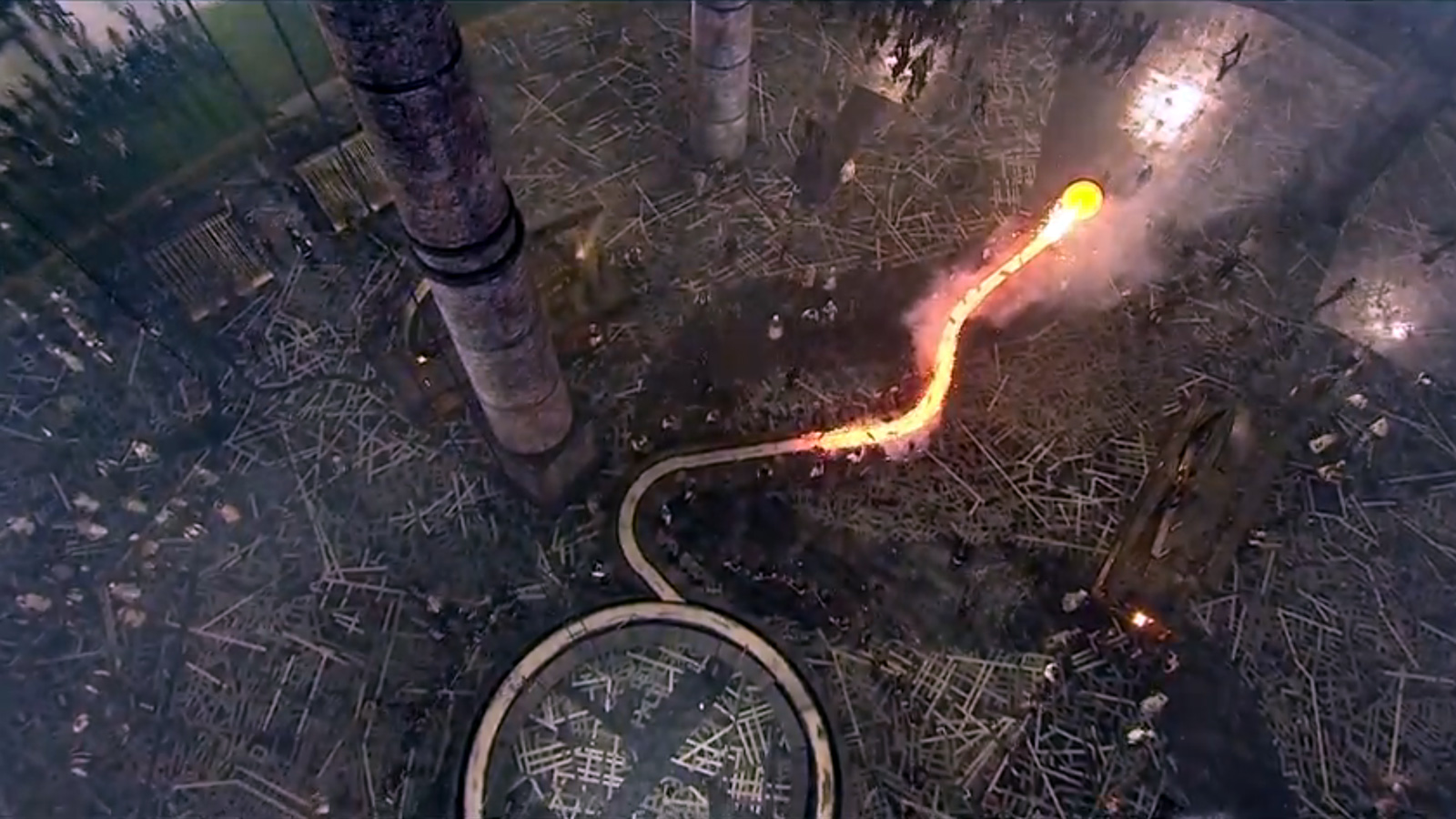

In Google Maps, the Olympic Stadium still features the decorations of the 2012 opening ceremony. The Thames forms the static centerpiece, albeit rotated clockwise 90 degrees and shrunk to fit precisely within a 400m running track. It just so happens that the orbital satellite from which images of the Olympic Park were taken was above at just the moment when the map floor was built.

Zooming in further, we see that this streetscape of London has no correlation with reality, but is formed from a tapestry of randomly scattered lines. The major parks appear in place, but it is the distinctive curve of the Thames that unmistakably signifies London. Here, the river reappears as an icon: flattened onto the stadium floor, flattened on the satellite camera, and flattened on our screen. As the stadium floor was covered with a Wordsworth-meets-astroturf landscape for most of the opening ceremony, it is difficult to discern when the map was unveiled. Referring back to the official video, we can see the fake river emerging slowly during the ‘Pandemonium’ section of the sequence. As the pastoral flooring is removed during this dramatised reenactment of the Industrial Revolution, the rotated Thames becomes a channel for molten steel. This simulated act of BP-worthy environmental catastrophe accomplishes what could not be achieved in reality: the triumph of technology over nature and the ceremonial erasure of the Thames.

Our version of reality is, literally, superficial; terra firma is the subject of Internet mapping sites, the solid ground on which we can stand. In 2009 the Google Earth database added data about ocean depths around the globe. This bathymetric analysis determines the exact colour that the seas are presented as; darker means deeper, with coastlines a very light shade of blue, like the Thames in the original EastEnders sequence. Pacific ocean ridges and trenches show up prominently through this mapping. Of course, the surface of the ocean is nothing like this projected world, but it serves as a beautiful texture and proof of our digital omniscience.

The contrast between flatness versus volume, and stasis versus dynamism is an endlessly debated point in western art. The form of stone sculpture is defined by the continuous enclosure of its outline; we read this silhouette as ‘solid’ even though it could be hollow. Yet sculpture depends on our physical presence to understand it; on the screen, what is rendered is real. To be believable, the digitised Thames only needs to be a surface with some ‘water’ texture and glossy lighting effects. This single flat plane is a close enough approximation of the river; we do not know its depth, because it is not necessary. We only need to know that it is the Thames, and therefore the virtual city surrounding it is London.

Despite the best use of graphic algorithms, the digital seams remain visible – look closely again at the Thames Estuary, where the river meets the North Sea. There is a clear visual boundary between where the aerial photographs end and the ocean-depth mapping begins. This distinction is, of course, artificial. If you were to walk along the Thames, from its source at Thames Head, down the mudflats of Essex and out into the sea, you would not experience any abrupt changes in depth. It is a smooth continuity, without boundary. There is no edge that marks the end of the Thames – the river simply dissolves into the sea.

GAIA

Rivers and their tributaries form patterns that look like trees – or rather, the root systems that feed trees. Over millions of years, surface water etches itself into rock, drawing the landscape in its own image. In turn, we read rivers as lines in the landscape, flowing into the ocean. Seen in this way, the Thames never ends. Its line extends itself in all three dimensions, above and beneath the visible surface of the world, a single continuous body held together by gravity.

Unfortunately, this Gaia-like holistic view is not how nations see their own river. Thames, Nile, Amazon, Seine, Tiber – all civilisations are very proud of their rivers, each believing theirs to be the most fertile, the most strategic, the most important. In truth, they build the terrestrial factors that allow settlements to flourish – agriculture, docks, bridges, wells, and sanitation. The river itself is left to itself, before being enclosed in dykes and embankments, or dammed and siphoned off. The river has played its part in nation building, and now remains as a token part of the urban landscape. It has to wait for resurrection.

Until the 1830s, the Thames was prone to freezing over during the winter months. Londoners would regularly hold ‘Frost Fairs’ upon its icy surface to celebrate. Heraclitus took the river as a word that represented a continuously changing object. To step inside the river, one had to be physically immersed in it. It is a liquid; with the body passing through its surface. In the Mediterranean climate, Heraclitus would never have come across a frozen river. With a surface of ice, the river becomes impenetrable – if you cannot step inside the Thames, would his aphorism still hold true? Or even more broadly – is a frozen river still a river? Or is it like the future ox-bow lake of the Isle of Dogs, suspended in a perpetual state of becoming?

Simulations can become reality, but only if we choose to ignore their inherent imperfections. Copies of objects are relatively easy to accept – when Roman reproductions of lost Greek sculptures are all that remain, we accept them. We find it more difficult to accept copies of the habitable world, and if we do, it is only because it is necessary. Like the holodecks on Star Trek that provide its crew with terrestrial environments during galactic voyages, it is only the absence of nature that makes us crave it.

Roman sculptors had the straightforward task of using the same tools to replicate stone with stone. The Thames is an infinitely more complex case: nature has to be replicated digitally. With computers, we can calculate the river’s geometry, its speed, colour, texture, and the surroundings that it reflects. Yet the more detail we see, the more we come to expect – what we now consider as real we will soon see as fake. No matter how machines continue to evolve, the river will remain, a symbol for us to project our dreams upon. While the perceptual gap between the original and its three-dimensional copy is shrinking all the time, the corresponding rift between the natural world and technology-obsessed civilisation continues to grow. Like the Thames, our illusions have no fixed depth. We never see the same river twice.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.