© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

Do you drive? I do not, cannot and will not, but my borderline phobic attitude to the motor car exists in tandem with a genuine, epicurean love for the smell of petrol; just as the olfactory bang of frying garlic hits me with Pavlovian ravenousness, the heady, metallic stench of a petrol station forecourt immediately renders me helplessly vulnerable to the catchpenny tat in the shop. Long car journeys punctuated by filling stops have caused me to invest in copies of magazines I don’t read, CD compilations I will never listen to and truly rebarbative wraps that bear as much resemblance to their advertised ingredients as I do to Lewis Hamilton. In a city, I can resist the onslaught of garish promotions, false economies and super-sized chocolate bars (‘£1 with any purchase!!’), but out at the oases of the A1 and the M4, I’m helpless against the diktats of the convenience store subliminal. As Half Man Half Biscuit put it in their typically facetious single ‘24 Hour Garage People’:

I’ll have ten KitKats and a motoring atlas

Ten KitKats and a motoring atlas –

And a blues CD on the Hallmark label,

That’s sure to be good.

Yeah, right. This litany of rubbish says it all for the British motorist’s consumer opportunities. Yet despite their subtopian architecture, the aforementioned mediocrity of their secondary wares and the faecal stench one encounters if forced to use their facilities, petrol stations hold many associations for me. Most of my childhood memories involve seemingly interminable car journeys between London, Edinburgh and what you might forgive me for calling the Northumbrian outback. We drove abroad, too, once all the way from Dunbar to Barcelona, via London, Troyes and Marseille. I don’t remember what, if anything, we actually did in any of these places, nor do I have much recollection of sitting in the car; in fact, my own distinctly non-linear childhood narrative consists almost exclusively of stopping for lunch in motorway service pitstops.

In Britain, we tend to think of petrol stations – if we think about them much at all – as rather sorry places, sad clusters of concrete and glass flogging off fuel and Heat. Searching for examples of such garages in film and literature, I emailed almost everyone in my address book for suggestions. The response that came in only convinced me of this: ‘What about Alan Partridge? He hangs out in a petrol station’. North Norfolk’s favourite son notwithstanding, my enquiries revealed that the British canon throws up precious few garagistes; I can think of Scott Graham’s profoundly depressing film Shell, set on a small garage in the Highlands where an innocent teenage girl and her epileptic father pump out their lonely living; there is Ballard, of course (though not as interestingly or comprehensively as one might reasonably expect), and Chris Petit’s remarkable 1979 road movie Radio On, in which the protagonist arrives at a very basic petrol station somewhere between London and Bristol where the filling attendant is played by – of all people – Sting.

American lore, though, puts the petrol station in an altogether more exalted position. There is nothing left to say about the Americans and their cars or about the Americans and their oil that is not already a cliché, but the simple fact is that if you’re going to travel the Big Country, at some point you’re going to need to top up the gas. From the immiseration of the Grapes of Wrath to the frontier romance of Edward Hopper’s Gas to Kerouac’s On the Road through to Easy Rider and the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, the filling station – preferably isolated and ever so slightly fly-blown – has become a favourite hangout for American cinema, art and literature.

As a venue for an action movie showdown, it is bettered only by the nuclear reactor, the very steep cliff and, of course, the White House. Should the camera focus on a petrol pump for more than a second, the viewer knows precisely what’s coming – the only doubt lies in whether or not the pyrotechnics unit can make the inevitable Ka-Boom sufficiently impressive to keep the teenage destruction junkies happy. In The Birds, Hitchcock slipped in a particularly nail-eroding tracking shot of a fuel leak puddling its way slothfully towards a man lighting a cigarette with a match, setting the precedent for copycat scenes in everything from Robocop to Zoolander to Breaking Bad.

Explosions aside, the attractions of the gas station to American artists are obvious. For starters, it’s a ubiquitous road trip image in a landscape where one can drive for hundreds of miles without seeing any other sign of life. Beyond this, if we are to accept the car as a symbol of personal freedom, then the petrol pump is a corresponding signifier of the limits thereof. Given that its primary purpose is to distribute a fuel that has ignited wars and brought down governments, it’s a powerful political image, too. One thinks of the endlessly repeated footage of the 1973 Oil crisis, automobile queues snaking miles back from the forecourt a neat metaphor for the sudden collapse of post-war prosperity.

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

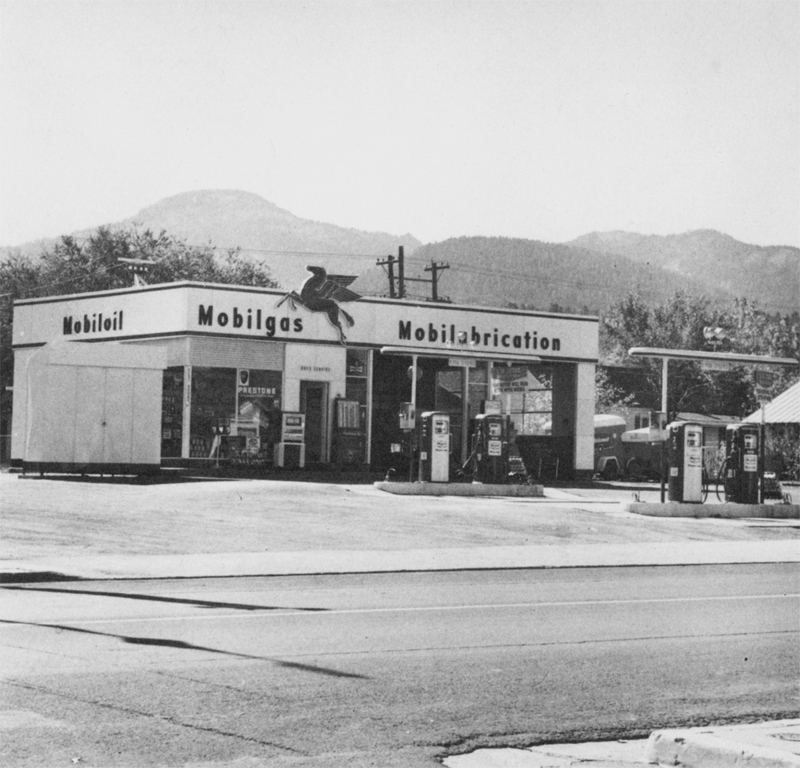

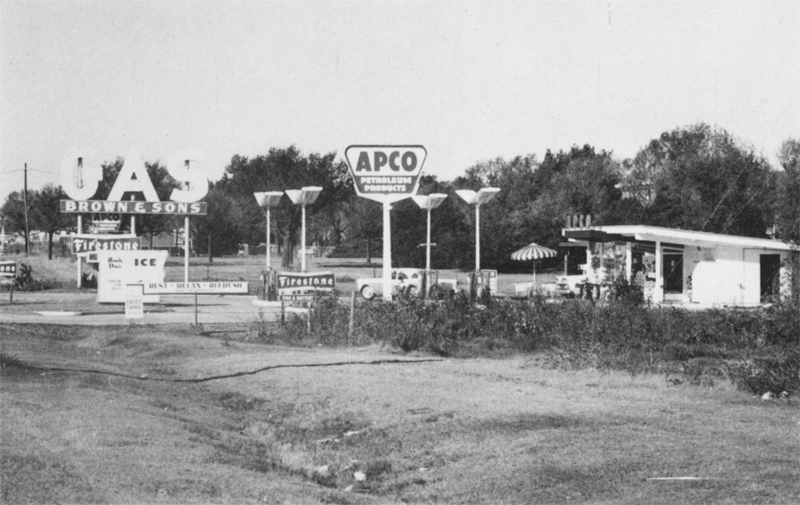

When Ed Ruscha compiled his 1962 book Twentysix Gasoline Stations – perhaps the most important demonstration of the petrol station’s significance in the index of American iconography – he was struck by the way that over a relatively short period of time, petrol stations had blended into the highway landscape:

On the way to California I discovered the importance of gas stations. They are like trees because they are there. They were not chosen because they were pop-like but because they have angles, colors, and shapes, like trees. They were just there, so they were not in my visual focus because they were supposed to be social-nerve endings.

Ruscha was identifying precisely the sort of liminal space Marc Augé wrote about in Non-Places. More than the airport or the supermarket (the former has at least a suggestion of glamour, the latter connotations of social class and spending power) the petrol station is perhaps the ultimate articulation of a ‘Non-Place’, an anonymous point of transit where ‘no lasting social relations are established’.

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

In spite or because of this, it still holds a strange fascination. The lack of any immediate characteristic is, I think it’s reasonable to claim, one of the principal reasons why the aforementioned artists, writers and film-makers chose to use the petrol station as a setting. Ruscha described his book as ‘a collection of readymades’, and delighted in the way its identikit reproduction echoed the anonymous proliferation of its subject matter. Similarly, Louis Aragon pontificated at length about the symbolism of the petrol pump in Le Paysan de Paris. Writing immediately after the First World War, he saw the filling station and its pumps as totems of modernity:

… the petrol pumps sometimes have the look of the deities of the Ancient Egyptians or those of warlike, cannibalistic tribes. Oh Texaco motor oil, Ecco, Shell, such great inscriptions of man’s potential! One day we will cross ourselves before your springs, and the youngest amongst us will perish for having stared at the nymphs in their naphtha.

The anonymity of mass production, mechanisation and – forgive the anachronism – globalisation, was then a rather exciting and utopian conceit. Whether or not Aragon’s pronouncements can be read as ‘prophetic’ (and I rather suspect they can’t), they had some effect on Walter Benjamin, who nodded to them in the title of Tankstelle (‘Filling Station’), the first part of his essay Einbahnstraße. In this short segment, Benjamin created a surrealist-inspired simile that compared the practice of literature and philosophy to industrial mechanics, equating educated opinion with fuel (‘one does not go up to a turbine and pour oil all over it’) and, turning the figurative language back into a tangible argument, praised the way in which new machine technology allowed for the rapid proliferation of ideas and knowledge.

© Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

From Alan Partridge to academic discourse, we’ve projected a lot of associations onto the canopy of the petrol station, enabled principally by the very fact that it is so demonstrably unremarkable yet at the same time so admirably utilitarian. For a catchier conclusion – albeit one that doesn’t quite scan – look to Welsh Britpop group Super Furry Animals’ hit ‘Herman Loves Pauline’:

Down the 24 Hour Garage,

Or any service station,

I lead my life in a quest for information

Practical advice for the modern pseud. But, sadly, I don’t drive.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.