‘If you’re gonna spew, spew into this.’

Wayne’s World (1992)

It was one of the first times I’d flown, and my delight in the mountain tops and puffs of cloud through the window was disrupted when another child across the aisle started choking on her own vomit, precipitating a nose-bleed. Stewards dashed for entertainment packs as adjacent passengers dipped into the pouches of the seats in front of them and whisked extra sick bags over to the girl’s father. Too late – there was red gunk everywhere – but the dad put a sick bag in his luggage, so they could laugh about it later, I suppose.

It seemed that air passengers had the edge on car passengers. Mile-high puking rang alarm bells, won the kindness of strangers and elicited specially designed paper products; carsickness, as I knew from many a journey in the family car, required that parents throw in a couple of old towels in readiness for the inevitable. My sister and I, how we dreaded the ‘Joyride’ packet of travel sickness tablets, with its toothy pin-up boy: although the pink pills tasted nice, they were a guarantee of hours in the car ahead – and they never worked. Towels turned wet, grainy and cold by journey’s end.

The airsickness bag has just a thin plastic lining separating it from a paper lunch bag, but it is prized by collectors. Their decades’ worth of artifacts point to a dispersed, international subculture and present a droll version of aviation history, from military development, to the rise of civilian flights, the growth of budget airlines and a world where the internet has brought everything closer. But anecdotally, I never hear about airsickness any more and so too sick bags are increasingly invisible on plane journeys. While this is something for which most people would be thankful, for a few, it is cause for concern.

This article is written at a point when the design and production of unique airsickness bags is decreasing and seeks to touch on the implications of this star in the descendent. It takes its cue from the salutary scene in Wayne’s World, where Wayne and Garth discover their buddy Phil in a bad way:

Wayne: ‘Phil, what are you doing here, you’re partied out man, again.’

Garth: ‘What if he honks in the car?’

Wayne: ‘I’m giving you a no-honk guarantee.’

Garth, doubtful, has the alacrity of mind to pull out a tiny crumpled Dixie cup from his breast pocket and offer it to Phil. If the receptacle is hopelessly sized for the job, the gesture protests that there is no such thing as a ‘no-honk guarantee’.

~

An ancient condition, motion sickness has proliferated as our travel options have increased. The very word ‘nausea’ is derived from the Greek naus, meaning ‘ship’, and the more we try to escape our confines, the more our landlubber condition is emphasised, from seasickness through to space adaptation syndrome or virtual reality sickness. It is this realistic detail that makes H.G. Wells’s War in the Air (1908) so much more palpable: ‘For a time he was not a human being, he was a case of air-sickness.’

The main hypothesis for motion sickness is ‘sensory conflict theory’. Roughly speaking, the fluid in the semicircular canals of the inner ear conveys three bubbles, which report orientation and motion to the brain; if the inner ear signals to the brain that you’re moving, but your eye says that you’re sitting still (according to the immediate environment) it’s a recipe for nausea. Among remedies, there are the bracelets that apply pressure to points on the inner wrists; medication, which has side effects and is therefore discouraged for pilots; and common sense, which suggests avoiding heavy boozing, wearing loose clothing and eating something light and dry before the flight so your stomach is neither too empty nor too full. Failing all that, you could try ginger tea, although in fact the only way to completely avoid motion sickness is to avoid travel altogether.

Sick bag aficionados are rarely the avid travellers that their collections might suggest. Like stamp collections, they serve as signposts to places that remain figments of the imagination. They are often the result of collaborative effort, rather than the trophies of individual travellers and bags might be sourced from aviation collectibles shows or purchased on Ebay, but are more often swapped and traded between peers or donated by well wishers. ‘There are really only a hundred of us who collect seriously’, says Steve ‘Upheave’ Silberberg, who ranks his collection of 2,422 bags (at the time of writing) in the top ten, and who was so generous as to open a window for me to their world. ‘Sometimes, people who have been collecting surreptitiously send me their entire collections when their wife tells them to get rid of it.’ Compare this to stamp collecting, the ‘hobby of kings and the king of hobbies’, whose popularity still rages today, with millions of devotees, celebrity names, associated societies and publications. In the shadow of their more illustrious stamp-collecting cousins, sick bag collectors amount to a small tribe of postmodern philatelists.

Any successful collection of stamps or sick bags, however, will have in common the combination of accumulation with arrangement. The nineteenth century publication The Stamp-Collector’s Magazine judged it expedient to publish a defence of their shared pursuit, which includes this description:

Its study also tends to induce a habit of observation of minutiae and order, the many differences of detail requiring to be carefully noted, and systematic arrangement being necessary in order to exhibit the beauties and the uses of stamps. (1867)

Sick bag collectors, like stamp collectors, conform to a mutually generated code for the systematic presentation of the bags. Bags should, of course, be unsoiled – neither wrinkled, folded nor stained. Further to this, German fan Wolfgang Franken, who has managed ‘Die Welt von Tuten’ since 1996, provides a roll call of 49 prominent ‘bagologists’ and an overview of their standards:

The modern collector doesn’t use shoeboxes to keep the bags in. The bags are put in transparent folders, and neatly filed in some kind of archive. Keeping an overview of one’s collection is done with a computer. Tables with date of acquisition and other data are kept about the bags. As every now and then airlines change their bag designs, there must also be a system for keeping track of this: bags with or without a logo, variations in colours, what material is used (paper, card, plastic, etc), closing mechanisms for the bags, and so on. (Airsicknessbags.de)

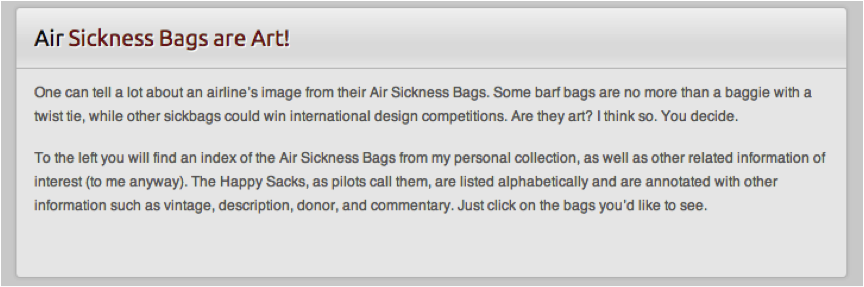

Online collections are usually sorted alphabetically, according to airline, country or region of the world, often with multiple editions from an airline; sometimes with an indication of whether the collector has doubles of a bag for trading. For bagologists, the emergence of the internet has been instrumental, but beyond the practical advantage of online bartering, sick bag websites serve as museums for treasured hauls. Bruce Kelly, of ‘Kelly’s World of Airsickness Bags’, hails from Alaska, and came to ‘airline art’ through spending so much time on flights. He says: ‘I briefly considered collecting safety cards but instead zeroed in on what I considered were the often over-looked and under appreciated little air sickness bags.’ His collection of 5,941 bags increases at a monthly rate of around 20 bags: it’s a commitment.

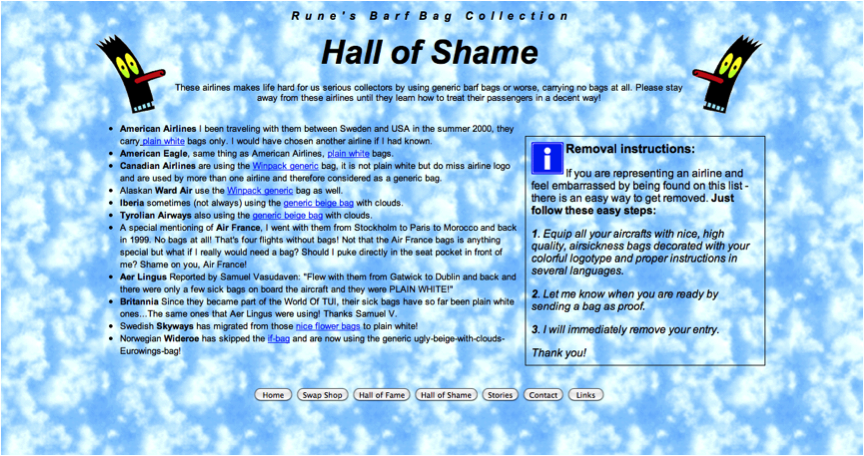

Kelly admonishes himself for being ‘computer illiterate’ but what is remarkable about his and his fellow collectors’ online museums is their shared organisational principles and aesthetic choices. Their styling reflects the rise of the web as a free-for-all. ‘Rune’s Barf Bag Collection’ (Sicksack.com) is a prime example – a static gallery imposed on a bitmap background of blue sky and white clouds. Rune Tapper’s obsession with sick bags was in fact a way of dipping his toe into the internet in 1993. The Swedish radio engineer, who also collects obsolete computers, was only trying to make his webpage stand out by posting curios, but his collection of five bags inspired emails from all over the world offering to augment the site. He credits donors with a hierarchical thanks page – from ‘First Class’ through to ‘Tourist Class’ – and he, like many others, has a page devoted to swapping.

Steve Silberberg, the self-described ‘curator’ of the Air Sickness Bag Virtual Museum (Airsicknessbags.com), graduated in 1984 from MIT with degrees in computer science and electrical engineering and has never even travelled outside of North America: his interest in sick bags was made entirely possible by the Internet. His museum has a sober maroon and grey colour scheme, indicating a more serious, self-aware approach. The collection is fully searchable and offers a wealth of links to other collectors, online exhibits, and to ‘Barfbags’, a forum for collectors counting 90 members. A humorous man, Silberberg’s interest is whipped up by bags that do more than act as a receptacle, and extends to examples from beyond the airlines: ‘I guess the seventies were a golden age. Big gaudy designs with games such as tic-tac-toe, Gin Rummy scorecards, “X & O”, pictures of dogs (use as a doggy bag) or even a kangaroo. I’m starting to get weepy…’

Danny Calahan, from Sydney, has been collecting sick bags since 1988 and his dedication was the subject of an actual exhibition, ‘Fully Sick’ at the Museum of the Riverina in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales in 2011. The 200 specimens in the show could be traced back to Calahan’s first memento, but he was quoted in The Australian with a warning tone: ‘I don’t collect anything else, once you enter the world of air sickness bags, anything else would be second-rate.’

The Guinness World Record holder for most airsickness bags does not subscribe to the open values shared by many other collectors. Niek Vermeuler, from the little Dutch town of Wormerveer, set out on his wacky pastime somewhat cynically, in order to win prizes. His 40 years in the game paid off, with over six thousand bags from 1,142 different airlines in 160 countries, but speaking in 2011, he struck a doleful tone: ‘I’m old now and my medical situation is best described as “the time is coming”. So I’ve started looking for a successor to take over my collection.’ Vermeuler doesn’t take into account that the time is coming for airsickness bags too: he will be looking for a caretaker rather than a successor.

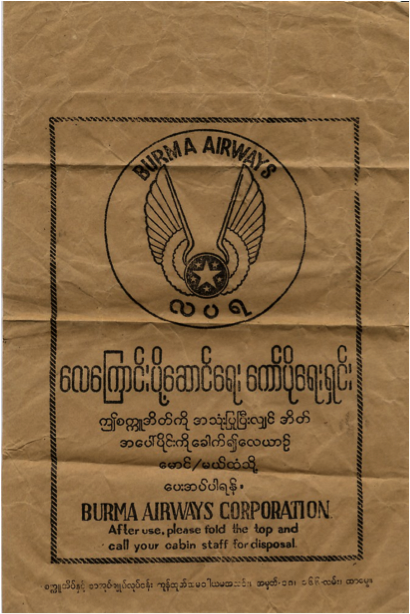

Burma Airways (1977), ‘Excellent old bag that’s paper and not even lined, from a country that no longer exists.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com

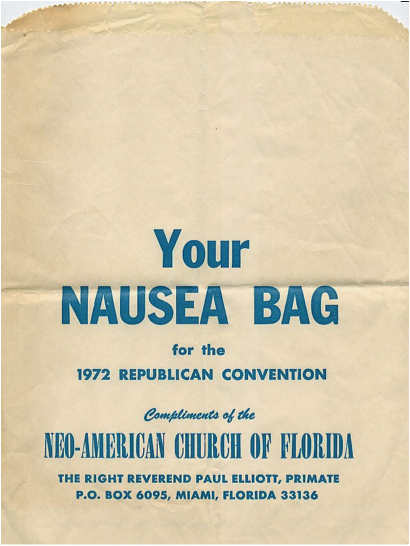

1972 Republican Convention (1972), ‘A beautiful museum piece — the essence of what this collection embodies.’ Steve Silberberg, Airsicknessbags.com

~

The outlook for Kelly, Tapper, Calahan, Silberberg and even Vermeuler is not good. Many airlines have stopped branding their bags, carrying plain white ones instead. I asked Silberberg, as a man on the front line, about the impact on his collection. ‘In the States anyway,’ he says, ‘airlines don’t like to brand their bags anymore. They seem to want to distance themselves from the possibility of nausea during flights.’

Up until the 1950s, queasy air passengers made do with card or waxed paper envelopes. So while inventor Gilmore Schjeldahl is usually first credited for building Echo 1 (launched by NASA in 1960, it enabled the first satellite telecommunications) his expertise in plastics and adhesives bore fruit earlier in his career. Back from World War II, the war veteran experimented with hot knives in the basement of his Minnesota home, developing techniques to cut and seal plastic – and this resulted in the invention of a bagging machine. Schjieldahl made the first custom design sick bag in 1949 for local airline Northwest Orient Airlines, with which the fate of commercial aviation was sealed.

If sick bags have a lower profile these days, it would seem symptomatic of travellers being less sick. When it comes to solutions, the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory remains phlegmatic, saying that one of the best countermeasures for motion sickness is simply adaptation (Webb, 2011). However, the primary factor towards a decrease in airsickness since Schjeldahl’s era must be the relative smoothness of journeys. Larger jet planes make for greater stability than earlier propeller engines; we benefit from improved weather radar systems and refined air traffic control, which enables less circling; and since in-flight smoking was banned in 1998 cabin air is no longer full of cigarette smoke. Precise figures for airsickness in the general population are tricky to gather but according to NASA research, only 1–2% of the general population experiences problems on commercial aircraft (Reschke, 2008). A British study into commercial flights observed that 0.5% of passengers reported vomiting alongside as many as 8.4% reporting nausea and 16.2% reporting illness (Turner, 2000). Lateral and vertical motion was found to correlate to sickness, though to an unpredictable extent because, the study admits, this is where an individual’s psychological perception of flying comes into play.

Sick bags were once a psychological tool – the attractive designs attempting to mask the horror of being sick on board. Collector and designer Helene Silverman casts a professional eye over her set: ‘Airsickness bags need to be solid, physically and graphically: immediate identification is important’, she said in 2002. ‘They are often designed in a super-clean Swiss style so as to remind you of vomiting as little as possible.’ But just as around half of all astronauts experience nausea in their first few days of space before gradually acclimatising, it seems likely that over the last 50 years the general flying public has simply toughened up.

A death knell for the airsickness bag was sounded by Virgin Atlantic in 2004, when they ran a design competition. Far from a renaissance, this marketing ploy confirmed that the place of sick bags in the air cabin was retro and risible. Agency man Oz Dean had been running ‘Design for Chunks’ since 2000, getting designers to ‘illustrate the usually plain in-flight sickbag’. Virgin caught on, and distributed 20 of winning designs in a half-million print run. The project attracted considerable attention and the six-month supply ran out after three months due to hoarders. Riding a wave, in 2005 Virgin carried a set of four promotional sick bags for the new Star Wars movie and video game (in the noughties, numerous airlines started selling advertising space on their sick bags). Again ahead in blue-sky-thinking, Virgin produced a man-sized sick bag, printed with a five-foot deluge of self-conscious text: ‘How did air travel become so bloody awful? First they took away the meals. Then, the pretzels. And then, the peanuts. All seven of them…’ etc. It’s a hop, skip and a jump to Lydia Leith’s commemorative sick bags for Will and Kate’s wedding in 2011.

~

Unique airsickness bags may offer a salve to the discomfort of aviation, but, like the in-flight meals, drinks, face wipes, pens and movies, such fripperies are falling victim to cost-cutting. Helene Silverman told me that the impact on her collection has been stark: ‘As a matter of fact, it has been impossible in domestic flying to add to the collection. It has been obvious that to cut costs, bags became plain white, so sad!’ That complaint is echoed by many of her peers. Kelly envies his European counterparts: ‘It is not easy for a North American to amass such a collection as most of the airlines based on this continent including Alaska persist in using generic white bags that do not identify the name of the airline.’ Rune Tapper chimes in: ‘We are very, very upset by this. Most North American airlines now use plain white bags – it is a disgrace!’

Tapper’s outrage is concentrated in a page on his website entitled the ‘Hall of Shame’. His pet hates are white bags, generic Winpack bags and worst of the worst, no bags: ‘A special mentioning of Air France, I went with them from Stockholm to Paris to Morocco and back in 1999. No bags at all! That’s four flights without bags!’ There is a certain irony to Tapper’s fury. He speaks with righteousness, as if he were making a stand for nauseous passengers, when arguably the airlines’ stinginess could be pinned on those collectors who have snatched all the samples from the aisles. For unique airsickness bags have gone the way of the Dodo.

Sick bag collections have no monetary value, but as their items become increasingly rare, they’ll glean a certain elegance from historicity – as will the websites that house them. Now the Internet is clickbait, but these sites are monuments to the early years of online pioneering, when it was the domain of the noble aficionado. They raise a toast – a Dixie cup – to a period when globalisation could be measured by a paper trail.

To comment on an article in The Junket, please write to comment@thejunket.org; all comments will be considered for publication on the letters page of the subsequent issue.